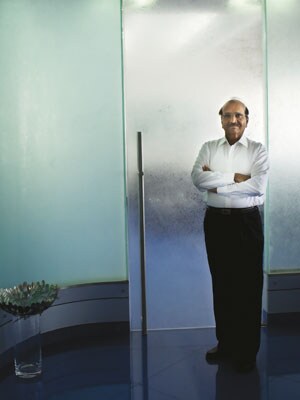

Where is Nirma's Karsanbhai Patel?

Nirma was once the poster child for entrepreneurship. Then its maverick founder decided to call it a day. His son wants to recast the firm, but is missing Karsanbhai’s spunk

Four decades after Karsanbhai Patel started Nirma out of a small shed in Saraspur, an Ahmedabad suburb; it’s hard to identify what this Rs. 4,831 crore company stands for. If looked at purely as a consumer goods company, it appears to have lost its way. With barely 10 percent of market share, Nirma, the detergent powder it manufactures, is no longer numero uno. It lost the top spot to Wheel, which was set up by Hindustan Unilever to battle Nirma.

Managers from rival firms who’d battled the company in the eighties and nineties say they’ve written Nirma off as a serious competitor. On the stock markets, it now trades at Rs. 213. Adjusting for a stock split and bonus, it is around the same rate at which it traded ten years ago. And not a single equity analyst tracks the stock anymore. It’s the kind of thing that is far removed from Karsanbhai’s call to arms once upon a time to make Nirma the largest detergent brand in the world. Though he continues to be chairman of the company, the Hindi film buff has practically retired from the business he founded.

Operational control is with younger son Hiren who is managing director. Elder son Rakesh is vice-chairman. On his part, Karsanbhai has chosen to focus almost completely on education and his life is now pretty much around Nirma University, which he founded in 1995. It is now the largest private university in Gujarat.

The 37-year-old Hiren is now remaking the business. People who know him describe him as a man in a hurry. He sees Nirma’s chemicals and fledgling healthcare business as key to its future and has made use of the company’s current cash flows to get into these areas. He also wants to get into cement when he reckons the time is right.

Nirma’s diversification began over a decade ago when the company decided to allocate Rs. 1,500 crore to set up soda ash and LAB (linear alkyl benzene) capacities, key raw materials in soap. Both ingredients were controlled by a small clutch of manufacturers with GHCL and Tata Chemicals controlling the soda ash; while Tamil Nadu Petro Products and Reliance Industries supplied most of the LAB.

“Over the past decade the company has moved from being a consumer centric business to a chemical business,” says a former Unilever director who has watched the company grow over the years. “(With all the backward integration) they thought they could do a Reliance in this business,” he adds. In 2007 the company acquired Searle Valley Minerals, a US-based producer of soda ash making it the world’s seventh largest producer. At Rs. 1,509 crore the chemicals business almost brought in a third of revenues last year.

Its plans in the healthcare space are no less ambitious. The company sees this as the third flank of their growth strategy after consumer goods and chemicals. In 2004, Nirma acquired Core Healthcare and started marketing IV fluids. At that time the company was making losses and industry watchers suspect it was acquired so losses could be offset against income taxes Nirma had to pay. Sales at this division have risen from Rs. 160 crore to Rs. 230 crore last year. In the next few years Hiren says he would like to become a global player in generics and over the counter drugs.

Still, for the time being it is the consumer goods business generates most of the Rs. 250 crore profit every year. In going after new growth areas Nirma seems to have decided that growth in the consumer space will be more difficult for several reasons. Firstly, the FMCG business has slowed down over the years. Hiren knows that unlike what it was two decades ago, building a national brand just by advertising on a single television channel is near impossible. Nirma was always seen as a low-end brand and to be successful in other categories, it would have to build new brands. That is a battle Nirma is loath to fight.

Secondly, in competing with multinationals HUL and P&G that have deep pockets to advertise their wares, well developed research and development facilities and a larger distribution reach, Nirma finds itself out of depth. It has also seen rising input costs. Last year its revenues in the soaps and detergents business declined to Rs. 1,787 crore from Rs. 2,109 crore a year earlier.

After much prodding, Hiren wrote in an email: “Instead of focusing only on volume growth, Nirma strives to maintain its margins by adopting a judicious mix of volume, price and quality driven strategies.” Both Karsanbhai and Hiren, however, declined to be interviewed either in person or on the phone. In fact, for almost a decade now, the company has shut its doors to the media.

Former employees say the company still sticks to its roots as a low cost producer. There is a constant emphasis on keeping costs low. The Patels are not known to be good paymasters and rarely offer a free hand to their employees. As a result, few professional managers have joined Nirma over the years. But as someone who competed with Karsanbhai for many years says, “In making these diversifications Hiren has shown that he can run disparate businesses. But where is the spirit of Karsanbhai the entrepreneur?”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)