For Indian Entrepreneurs The World Begins at Home

Indian entrepreneurs are reining in their wanderlust for globalisation and making more selective bets. In the process, they are rediscovering their home market too

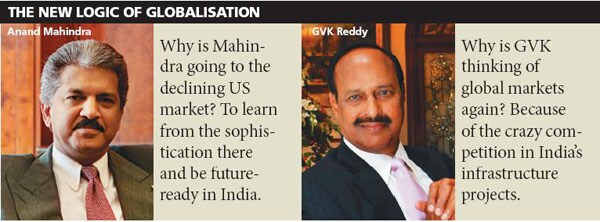

Sanjay Reddy shudders as he remembers the nine months of competitive madness. The GVK Reddy group scion recalls the media frenzy sometime in 2007, when arch rival GMR group won the bid for expanding and managing a secondary airport near Istanbul. Stock market analysts, who often compared the two groups, wanted to know if GVK had a matching global strategy. GMR’s share price had zoomed. And as the head of new business development, 42-year-old Reddy was feeling the heat.

He quickly formed a core team to evaluate transactions in infrastructure all around the world. “We literally combed the world,” he says. GVK chased projects in Russia, Prague, Mexico, Singapore, Spain and many other places. The team even looked at a small airport next to a church in London. Such was the hurry.

But after crisscrossing the globe, Reddy and his team took stock. The market was at an all-time high. The deals were highly leveraged. And there was the tell-tale sign: almost all the sellers were large private equity funds. That’s when the penny dropped. “We realised that we had been completely carried away by the hype around globalisation,” admits Reddy. “As developers, the maximum value for us as developers lay in green-field [new] projects, and not in brown-field [upgrade] operations.”

The GVK group may have escaped the blushes in the heat of the three-year mergers and acquisitions frenzy that started in 2005. Not all Indian frontline entrepreneurs were quite as lucky. Take G.M. Rao of GMR group. In 2008, the Bangalore based infrastructure entrepreneur spent $1.1 billion for a 50 percent stake in InterGen, a US-listed power company that owns 12 power plants across Europe and South America. The idea was to use the InterGen experience to bid for Ultra mega power projects in India. Today, faced with a huge debt burden and a falling stock price, Rao is looking for a buyer for his group’s stake in InterGen. In fact, his global misadventures may have partly resulted in Rao dropping five places in the Forbes India Rich List since last year, losing 18 percent of his net worth.

So here’s the key question: Where would frontline Indian entrepreneurs place their big bets over the next five to ten years? With growth in India offering compelling opportunities, it is perfectly intuitive that they turn their attention away from globalization and focus on home.

And the reasons are fairly obvious. Growth across developed markets in the US and Europe have petered out. But Asia, led by China and India, continues to be on a roll. “The world is likely to see two-paced growth,” says Boston Consulting Group’s managing director Arindam Bhattacharya.

Over the next ten years, the Indian economy is expected to treble in size from the current $1.4 trillion making it the fifth biggest economy in the world. “Other than China, the growth in India is clearly unprecedented. And it, therefore, needs resource mobilization at an unprecedented level,” says Adil Zainulbhai, managing director, McKinsey & Co. Naturally, the global trip of many Indian companies is reaching its destination back home.

That’s not to say that all Indian entrepreneurs have bid goodbye to their global ambitions. On the contrary, expect some of them to continue buying assets overseas, shopping for technology or even selectively hiring expat managers. There are several examples of this: Mahindra & Mahindra recently agreed to buy Korea’s Ssanyong Motors, Dabur bought Turkish company Hobi Kozmetic and Reliance bought stakes in three shale gas assets.

In each of these cases, the logic of globalisation has undergone a subtle shift. We’ll come to that in a bit, but let’s first get a handle on how the eastward shift in the centre of gravity of world business is shaping the Indians’ strategy.

The US will move from being a $11 trillion economy to $13.5 trillion over the next decade. And Asia will jump from $7 trillion to $21 trillion. Put simply, the Asian economy will grow by adding two and a half times India’s current size every year, says Janmajeya Sinha, chairman, Asia Pacific, Boston Consulting Group.

Almost on cue, some of the biggest firms around the world are either here in India or on the verge of entry. Multinationals in a diverse set of industries like GE, P&G, IBM, Nokia, Samsung, Wal-Mart and Toyota are expected to ratchet up their investments here over the next five years. The competitive intensity will mount, exactly as it did in China over the past five years. The action is palpable even in a somewhat troubled sector like Pharma: The recent Abbott deal to buy out Piramal Healthcare for $3.7 billion has reignited the buzz in the domestic pharma industry.

Anand Mahindra: Indiatodayimages.com; GV Krishna Reddy: Indiatodayimages.com

On the other hand, the entrepreneurial renaissance in India has led to even unknown entrepreneurs discovering new sources of value creation. The Forbes India Rich List over the last two years offers some evidence. This year, there are 12 new faces which have broken into the List, even as the benchmark for entry into the list has risen too (see page 56). We are betting on the premise that this churn will gather momentum. The upshot: incumbents will face the music from competition from hitherto unknown sources.

Over the past five years, much of the rhetoric in business circles was about being globally competitive. “Today, the crucial question is how to remain competitive even while being focused on the home market?” says Zainulbhai.

Time was when Indian entrepreneurs embraced globalization with a “We-can-Conquer-the-World” mindset. Mature with experience, they are now going in for a more selective and considered approach. So what are the new rules of the game?

Hedge Against Home

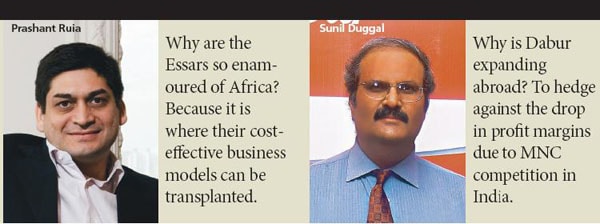

Sunil Duggal would count as the favourite man of the Burmans (of Dabur). Since he took over as group CEO in 2002, Duggal has seen Dabur’s market value quadrupling. Yet for the last few years, Duggal has been driving the firm to expand in Africa, Middle-East and South-East Asia. As he sees it, India is the big prize for most multinationals around the world. Already, in the past couple of years, operating profits have been coming down as multinationals like Unilever, P&G and Pepsico trained their guns on the Indian consumer packaged goods business. The valuations of any acquisition targets have shot up. “We are ready for a round of shoe-pinching in the mainline toiletries and foods business,” admits Duggal. As a strategic response, he’s quickly trying to ramp up Dabur’s presence in markets like Africa. Africa is almost as big an emerging market as India. What’s more, competitive intensity is a lot less compared to India. And Africa is at a stage of evolution that India was ten years ago. Plus, there’s the advantage of a first-mover advantage.

Duggal set up an entirely separate supply chain (read local manufacturing) to serve these markets. The start-up costs may be high, but once the break-even mark was crossed, the operating leverage would become healthy. The strategy seems to be on track. Already 22 percent of Dabur’s top line is from overseas and its operating margins there are actually higher than in the Indian business, says Duggal.

And to defend his turf in India, he’s decided to avoid head-on competition, and instead settle for positions that lie at the periphery of the core markets—and cede the centre to multinational competition. “We also have a relatively free run in categories like Ayurveda and herbal, where multinationals have no presence or knowledge,” says Duggal.

Business Model Advantage

It’s a variation of the same logic that has driven Sunil Bharti Mittal to expand his telecom business in Africa and a string of emerging markets at a time when margins in the Indian market are coming under pressure. And today, Essar is doing much the same in Kenya and Nigeria. “We’re taking a proven business model from India to these markets,” says Prashant Ruia, group chief executive officer of the $15 billion Essar group. African telcos have a high-cost high-price model that keeps penetration levels low. With their minute factory model, Essar and Bharti have begun moving the business into high volume, low margin business and changing the profitability of the business as well.

Ruia points out that almost 80 percent of his group turnover straddling power, oil and gas, shipping, telecom and BPO originates from India. And that won’t change over the next five years. India is set to become the world’s second biggest steel market after China. Yet in 2006, Ruia led a big foray into the US and Canadian steel market with two major acquisitions, Algoma and Minnesota (largely for iron ore).

Turning around the 4-million-tonne Algoma plant wasn’t an easy proposition. The Ruias had to face union protests and returning it to profitability took nearly four years. How the Algoma experience has influenced Ruias’ ambitions in buying any future steel manufacturing capacities is not clear. The chances are that they may desist from making any big buys in steel manufacturing assets, given the spectre of large overcapacity in the industry.

Prashant Ruia: Vikas Khot; Sunil Duggal: Indiatodayimages.com

But under their new chief executive Malay Mukerjee, Essar Steel is taking a strong position in value added steel both in India and in markets like UK, Australia and Malaysia. That means setting up large service centres in key markets to convert basic steel into customized sizes for local customers. Last month, it acquired Servosteel, the largest steel processor in the UK. It is also in the process of setting up six such centres across India. Not only does it help Essar serve global customers better, it is able to improve margins and deliver better returns than its manufacturing led model.

Shopping for Technology

Mukesh Ambani may be India’s richest businessman, but with a cash hoard of nearly $6 billion, the senior Ambani may have a problem of plenty. Finding new avenues to deploy the cash where it’ll earn a more than the hurdle rate of 20 percent isn’t easy.

In the same period when Ratan Tata and Kumar Birla were making big-bang acquisitions, Ambani too nearly ended up doing a mega deal or two in the petrochemical space. Perhaps he was looking to develop beachheads in the US market. But fortunately for him, the deals didn’t go through. Soon after, the international markets tanked, and money supply and demand both dried up, causing considerable grief for both the Tatas and the Birlas.

Today, Ambani is shopping for shale gas assets, which are seen as the next frontier in the energy space. Although Ambani hasn’t revealed his hand, insiders suggest that he plans to acquire the knowledge and the technology required to focus on shale gas assets back home. India has large tracts of unexploited shale gas deposits. So far, an incumbent like ONGC has simply not been able to get its act together. Its big constraint: lack of technological prowess.

Innovation Capital

When Jaguar Land Rover was on the block, M&M vice chairman and MD, Anand Mahindra, was in the queue with Ratan Tata to buy the firm. But once the valuations soared, Mahindra get out of the race. Two months ago, he again stepped into the ring, this time to buy out Korean SUV maker Ssangyong Motors at a more modest valuation and thus gain the product portfolio to reach out to emerging markets like Russia and Western Europe.

The world’s biggest auto makers are headed to India. And there’s no way that M&M will be able to defend its turf in SUVs and pickups without the requisite portfolio. “Today, if you’re not in touch with the world, you could miss out on new sources of innovation. The price of insularity is simply too high,” he says. Just as GE and Nokia are waking up to unknown competitors from emerging markets, Mahindra says his firm needs to alert to any new player anywhere in the world who can disrupt the global game. “At the risk of sounding trite, we are in a global village,” says Mahindra. The obvious question is: why target a declining market like the US for pickups? The level of sophistication is so much higher, in terms of fuel standards and emission norms. And that experience is making him future-ready in India.

Post-script: A few months ago, Sanjay Reddy and his team were placing bids for a series of major road projects being awarded by the Centre. The level of competition was stunning. There were as many as 50 bidders in the fray, many of them new to the business and unaware of its risks. It was all the way a race to the bottom. “I hadn’t even heard of at least half of them.” Eventually, GVK managed to win just one project. This bidding frenzy in India has made Reddy take another good look at international opportunity, just in case.

(Additional reporting by T. Surendar and Ashish K. Mishra)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)