PI Industries: Focusing on small details to win big

By focusing on custom research for global agriculture companies, PI Industries has carved a niche for itself and grown faster than competition

Mayank Singhal, Vice chairman and Managing director, PI Industries

Image: Amit Verma

Mayank Singhal, Vice chairman and Managing director, PI Industries

Image: Amit Verma

When Mayank Singhal sits down to talk about the history of PI Industries, he speaks with infectious enthusiasm. From a small edible oil business founded 77 years ago by his grandfather PP Singhal, the business has created the most value for its founding family and shareholders.

Listening to Singhal, 51, as he recounts the twists and turns of its long journey, the inflection points, the breakthroughs and the quest to push the accelerator on growth makes it clear why PI, in all likelihood, has a long runway ahead. As an entrepreneur, Singhal is constantly looking for new growth opportunities. The business now has a market cap of ₹58,000 crore, but investors think it is still good for 18 to 20 percent growth every year, and are pricing that in.

The spike in market cap that has come in the last decade is primarily on account of PI Industries becoming big in the custom synthesis and manufacturing business (CSM). In this business, it offers process research, analytical development and manufacturing for global agri-chem companies. “We managed to break into this market as global companies were comfortable that their intellectual property (IP) would be protected. They see us as a knowledge partner,” says Singhal. It is a key advantage the company has over rivals from China. This business (the other being the domestic agri chemicals business) brought in 75 percent of revenues in FY23, up from 59 percent in FY15 and 37 percent in FY10.

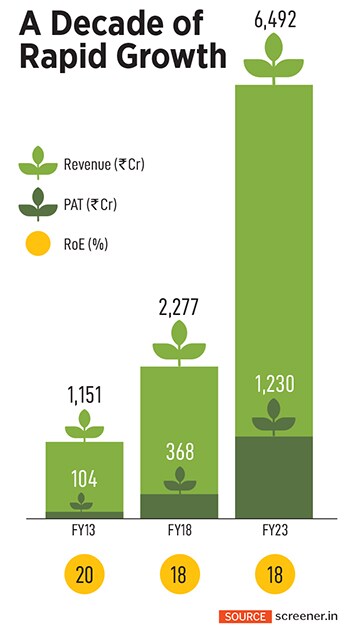

The last decade has seen revenues compound at 19 percent a year to ₹6,492 crore in the year ended March 2023. In the same period, profitability has grown faster at 29 percent a year to ₹1,230 crore. This rapid growth has resulted in the stock moving up 31 percent a year, taking its market cap to ₹58,000 crore. PI’s CSM business has become a strong moat as no other Indian agri-chem company offers this service at the scale that PI does.

The company has added more scientists and researchers in the last two years—from 228 in FY21 to 473 in FY23. The Indian agri-chem export market is also a direct beneficiary of the global China + 1 strategy. As per the World Trade Organization, India is now the world’s second largest agri-chem exporter with exports totalling $5.5 billion in FY23.

During this period, Singhal worked at reorienting the company from a commodity play to one with a strong scientific backbone. He’d seen the business operating as a distributor of agri-chem products and knew that he’d have to deal with poor business economics. That was not a game he was interested in playing. Instead, he would work with global players and licence their products for India—get their price points lower—and distribute them. It was a high-risk gamble. If it succeeded, the payoffs were high, but there was also the risk of a blow-up if it failed.

During this period, Singhal worked at reorienting the company from a commodity play to one with a strong scientific backbone. He’d seen the business operating as a distributor of agri-chem products and knew that he’d have to deal with poor business economics. That was not a game he was interested in playing. Instead, he would work with global players and licence their products for India—get their price points lower—and distribute them. It was a high-risk gamble. If it succeeded, the payoffs were high, but there was also the risk of a blow-up if it failed.