A House For Mr. Biswas: Tata Housing's Low Cost Township

Tata Housing's low-cost township on the outskirts of Mumbai isn't charity. The company may well have cracked the secret of building such homes profitably

Chances are you don’t know what an ‘exurb’ is. It is hard to understand its meaning until you see Boisar. This is a place 90 km north of the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai. At this place, Tata Housing is putting in place a massive 1,500-home affordable housing project alongside another 1,300 mid-price homes. Once complete, the township would come fitted with schools, shopping centres and a primary health care facility. Amid landscaped gardens, there will be space for children to run and play. The property even has a river running through it. Essentially, the works.

This is an exurb: A suburb of a suburb.

If you think that sounds like a lot to pack in for houses that won’t make a lot of money for the company, you’re going down the right path. At a price of Rs. 4 lakh — Rs. 8 lakh, the affordable homes aren’t very remunerative for a developer. “Developers are rarely interested in this business as there is no top-line,” says Nayan Bheda, chairman of the Neptune Group, a real estate development company.

The surprising thing is that even though Boisar is really far from Mumbai, every single flat in the Tata Housing project is sold out. This has got the CEO of Tata Housing, Brotin Banerjee, to take his plan national. He has launched two affordable housing projects christened Shubha Griha, in Boisar and Vasind (situated 80 km from Mumbai), and has even started a new subsidiary, Smart Value Homes. The company says it is at an advanced stage of tying up land in Bangalore and expects to make announcements for similar projects in Hyderabad and Chennai soon. In all, the company expects to develop 20 million sq. ft. of low-cost homes across the country.

What makes Tata Housing attempt low-cost housing when this segment really isn’t very profitable? Margins in this space are typically half of what they are for other segments. But as Banerjee explains, “We aren’t doing this for charity.” Banerjee believes the company has figured out a way to make the project viable.

Low-Cost Challenge

Unlike other developers, Tata Housing had started to look at affordable housing in 2007 before the slowdown hit. At that time the company was working only on premium housing projects. But data pointed them towards a much larger opportunity at the bottom of the pyramid. (Banerjee also admits that they were afraid a bubble could be building up in some markets.) The company estimated a shortage of 24.7 million units with 70 percent of these being in the affordable housing space.

Ibrahim Sheikh, who owns a garage in Colaba in South Mumbai, is an ideal customer for the company. For the last 20 years, his family has been living in a chawl (tenements with one- or two -room units) in Bandra, a Mumbai suburb. Earning Rs. 15,000 a month, he lived a hand-to-mouth existence. “Who could afford a house in Bombay?” he asks. When he heard of the Tata project through his brother, he rushed to book.

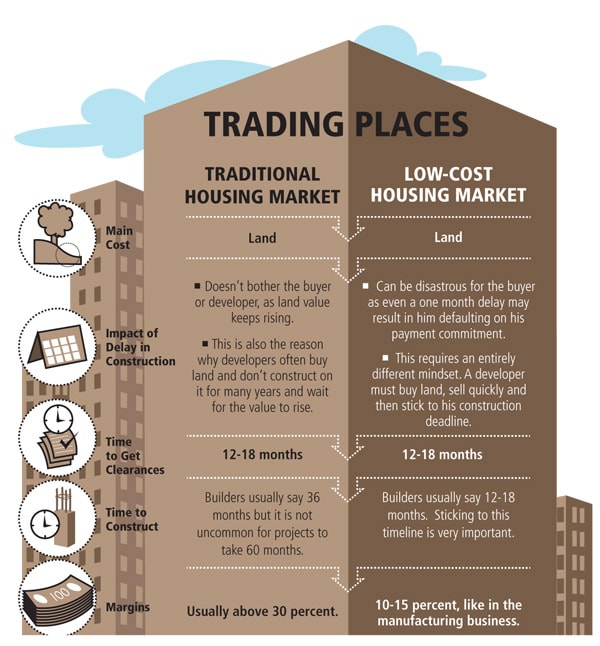

So while there is no disputing the immense opportunity, the challenge for every developer is to come up with a sustainable business model. Affordable housing works very differently from housing for other income groups (see graphic) and so speed of execution is very important here. This is not something most developers are used to.

Bala Venkatachalam, a project manager with the Monitor Group, has worked with developers to understand the problems they face in land acquisition, obtaining clearances and construction. He concludes that the margins and skill sets required make this an attractive proposition for only those with a manufacturing background. Tick the Tatas. The Mahindras are also mulling an entry into this.

Banerjee’s own experience of selling branded salt against commodity salt and at the same price at Tata Chemicals came in handy. The key learning: Low cost means a completely new business model; from sourcing to distribution and from pricing to margins. In much the same way, Banerjee and his managers have questioned every assumption — design, construction, sales, preventing speculative buying and consumer finance — to do this.

So how do you get the prices down? Their own experience and research told them that affordable housing would only succeed if the selling price was no more than Rs. 1,400 – Rs. 1,450 per sq. ft. The team began slashing costs.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

"The biggest cost for a developer is land,” says Bheda of Neptune Developers, who has also made his own affordable housing development in Ambivali near Thane. Most developers, Neptune included, prefer to buy land to take advantage of the appreciation in land costs before selling houses. Banerjee didn’t do that because the company would build, sell and get out before the land price appreciated too much. He instead chose to partner with landowners on a revenue share basis with 10 percent to 15 percent of the cost of land being paid upfront and the rest paid out as a percentage of sales.

Next came the cost of designing the houses. This is where the developers often trip up as they equate low cost with low quality. Tata knew that here a cookie cutter approach would work best. Houses once designed would have to be good for construction at any project in India, lowering costs by 3 percent. There is no leeway for any customisation or change in layout.

Know Thy Customer

To understand how their potential buyer currently lived, the team spent a month researching 100 low-income families in Mumbai and Bangalore with an annual income of no more than Rs. 3 lakh. The team was stunned to discover how people lived. Most homes had five people staying in a 100 sq. ft. room. A mezzanine floor was found in most homes and people often slept in the kitchen.

The survey constantly pointed to the fact that people had a lot of pride in their homes. “They just don’t accept shoddy construction. To give the homes a clean look, we put white tiles for flooring, something that an affordable housing developer doesn’t usually do,” said Rajeeb Kumar Dash, head, marketing services, at Tata Housing.

The next area of cost cutting was the construction material. No bricks were used. Walls known in trade parlance as shear walls were made wholly of cement, which made them much stronger. More importantly, these are maintenance-free, lowering long-term costs for the residents, according to B.K. Malagi, vice president, engineering, at Tata Housing.

For instance, rooms were designed in such a manner that tiles fitted them without being broken. All this led to a construction cost of Rs. 650 — Rs. 700 per sq. ft. for Shubha Griha flats.

But only making Shubha Griha flats wouldn’t ensure a decent return. Most developers have failed to innovate and come up with a way to increase margins, says an industry analyst who requested not to be named.

The Profit Ecosystem

Tata Housing addressed this in two ways. First, the project comes with commercial real estate that is typically sold at thrice the cost. A doctor’s clinic could easily fetch the company Rs. 10 lakh and a shop Rs. 5 lakh. “Having a mix of commercial and residential is a good idea, as it helps with improving margins but you have to keep in mind that commercial property can only be sold when the project is almost complete and it could make it harder for a smaller developer to manage cash flows,” says Jasmeet Chabbra, director, investments, at realty fund IndiaReit.

Second, the complex also comes with houses in the Rs. 15 lakh to Rs. 35 lakh range. Boisar will have 1,300 such flats sold under the New Haven brand. At the same time, care has been taken to keep Shubha Griha and New Haven separate. They have separate societies and entrances. When it launches Shubha Griha across the country, the developments will invariably come intertwined with New Haven.

Selling the Dream

While designing and constructing affordable houses is a challenge, the team was also acutely aware that selling them would require careful planning. How does one sell houses to a segment of population that probably never reads newspapers? How does one sell houses to someone who receives his salary in cash and has never opened a bank account? And most importantly, how does one sell to someone who never thought he could own a house?

Marketing usually makes up 3-4 percent of costs for a housing project. Here the team had to lower them substantially. The only way to do this was by eliminating the sales function — usually a core in housing projects. So, the marketing team took over and worked on advertising campaigns.

Advertisements were only in vernacular papers and on trains. Equally, they were hard hitting. One ad read: “Yeh chula aap ka hai par ghar nahi. Agar ghar bhi aap ka hota toh khaana kitna accha hota (This stove is yours but not the house. If the house was yours too, how wonderful the food would taste).”

Accepting bookings was another potential headache for the company. It would have to recruit agents, train them for what was in effect a one-month job. Here it chose to do what another group company, Tata Motors, had done while selling the Nano. It tied up with the State Bank of India.

Forms were sold for Rs. 200, which took care of the bank’s administrative costs and a draw was conducted for the 16,500 bookings received. Tata Housing didn’t hire additional personnel and all questions regarding the project were answered by the bank. KPMG conducted the lottery. Tata Housing, for its part saw to it that no one is allotted more than one flat. As a result, marketing expenses for the project were just 1 percent.

Financing homes is another concern for applicants. Raslal Mahato, a cook living in Powai, a suburb situated in the north-east of Mumbai, says he spent two years searching for homes between Virar, a suburb in north Mumbai and Vashi in Navi Mumbai. But for Mahato, who earns Rs. 10,000 a month, every time the deal failed because he wasn’t able to secure financing. Realising this as a major issue, Tata made sure it had tied up with a microfinance lender.

One of the companies it tied up with is the Micro Housing Finance Corporation set up to address this segment of the population. Madhusudhan Menon, director, says that the company was set up for buyers like Mahato who have no link to the formal banking sector. Interest rates are capped at 14 percent and MHFC insists that buyers move into their houses within three months of possession to avoid speculators. Otherwise interest rates are hiked.

But the model has its critics. They point out that Mumbai is unique in that it has a well-developed transport network. People are used to commuting for upwards of an hour to get to work. In places like Bangalore and Hyderabad, it is possible to get a one-room house for under Rs. 2,000 a month just 5 km from the city centre.

“For now, the Tata name will carry them far and allow them to get land across the country. These are advantages we don’t have and this makes it next to impossible to address this space,” says a rival developer.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)