Deccan 360 Faces Turbulence

Maverick entrepreneur Captain Gopinath’s logistics venture has been grounded because he can’t seem to get a handle on operations

“I’m being towed by a fish and I’m the towing bitt. I could make the line fast. But then he could break it. I must hold him all I can and give him line when he must have it. Thank God he is travelling and not going down.”

What I will do if he decides to go down, I don’t know. What I’ll do if he sounds and dies I don’t know. But I’ll do something. There are plenty of things I can do.

- Old Man and the Sea,

Ernest Hemingway

As April drew to a close, Captain G.R. Gopinath, the intrepid entrepreneur, realised it was closing time. The aircraft of his company Deccan 360 were grounded. The trucks had stopped running. The IT centres and the service centres were shut down. The Rs. 110 crore that Gopinath raised from Reliance in April 2010 is gone, as is most of his other money. His biggest customers are fuming and many of his franchisees feel betrayed. His key executives with their salaries delayed for two months are demotivated.

Entrepreneurs know adversity. It is what makes their ilk different from the nine to six desk jockeys. Gopinath certainly has seen many tough times but this situation is not pretty. In less than 15 months of operations, two CEOs had left as has the head of sales. Sometime this week, he wants to launch his company in a different and smaller avatar. Yet, resumes from Deccan 360 employees have flooded the market. The much promised Nagpur hub has not taken off.

The company is said to owe Rs. 16 crore to its truckers. Reliance did not respond to a detailed questionnaire, but people close to Mukesh Ambani believe that the way things stand, he is in no mood to invest any more money in this venture.

Is Captain Gopinath unlucky this time around or were his plans unrealistic? There is no doubt that the Captain was aggressive. He had, after all, a thing or two to prove after he had to sell his company Air Deccan to Vijay Mallya. A non-compete agreement meant that he couldn’t start another airline. But his heart was in aviation. (We suspect it will always be that way because even now he is reported to be trying to expand his venture in the charter segment. But that story is for another day!). Despite several requests Gopinath did not speak to us. Till the time of writing the story, he was stationed in Delhi trying to get his charter business in to fifth gear.

New Dream

Gopinath wanted to build a logistics company that would revolutionise the industry. Sitting in his heritage house in Bangalore, in an interview given to us in October 2009, he spelled out his vision. It was grand and it involved planes. He wanted to connect 17 airports and 24 cities by three Airbus A310s and seven smaller ATR 42 turboprops.

According to him, the market opportunity was always there. An investor presentation made by Deccan 360 in April 2009 put the size of the logistics industry at $624 million in 2007, of which 60 percent (in revenue) came from air. Blue Dart was the only integrated logistics company in India with its fleet of seven aircraft. Gopinath’s aspiration was to offer a service better than Blue Dart and take away 20 percent share in the next five years. By the end of FY 2010 he said Deccan 360 would have revenues of $73.5 million. The reality is much more sobering. For the year ending July 2010 (for which results are available) the company had revenues of Rs. 43 crore (just over $9 million) and losses of Rs. 200 crore (around $44 million).

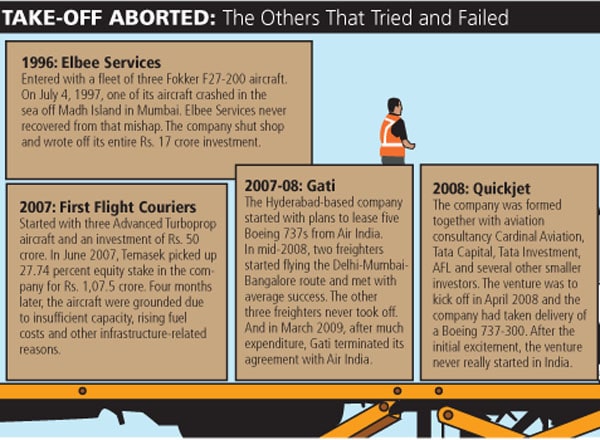

So what happened? To be fair to Gopinath, he did set out on a difficult task. The road to express logistics business is littered with failed ventures.

In 2009, as Gopinath was getting ready to launch Deccan 360, he had two options. One was to scale up gradually, start with surface transport, rent the belly of passenger aircraft of other airlines, and as more customers came on board, increase capacity by leasing out cargo planes. This was the conventional model used by players like Blue Dart. This approach was tried and tested. The downside is that it would take much longer. A bigger problem is that marquee customers, say Nokia or LG, would want an integrated solution. They would want to deal with just one vendor.

Go For Scale

That’s where the second option came handy. Gopinath decided to build it on a scale from the word go, like a telecom player setting up the infrastructure to connect everyone from day one. He is a gutsy entrepreneur who had always taken big bets. “When I get an idea, I am possessed by it,” he once said.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

To achieve this scale in a short period of time, Gopinath decided to use some trickle-down entrepreneurship. He decided to rope in franchisees to tackle the pick-up and delivery — the last mile — while he would handle the core of the network.

Most companies use a mix of franchisees and company-owned outlets as their service centers. The entire service delivery network in Deccan 360 is made of franchisees. The idea was suggested by Mohan Kumar, a director on the board of the company and a close confidante of Gopinath.

Kumar, a chartered accountant by profession, had earlier helped Gopinath set up Air Deccan. Kumar’s logic was that a franchisee-based model would help scale up operations in a short time and also cut down on the capital required. On paper this looked like a good plan and in a matter of months, Deccan 360 had more than 45 service centres employing 600 people. Now that this massive network was ready all it needed was customers. Unfortunately, they did not come.

Where Are the Customers?

The first flight went with all of 350 kilogrammes. “I felt people were laughing at us,” says a franchisee. Admittedly, the first day is no indicator of success. FedEx had just 186 shipments on day one. But demand caught up with the infrastructure soon.

During the early days, that’s what Gopinath believed too. “There are several companies which have logistics bill of over Rs. 50 crore. All we needed were 8-10 of them,” says Kumar. But it was a tough job convincing them to use Deccan. Customers, even those who had been telling Deccan 360 that they were waiting for a model like this were slow to switch. In many cases like those of Titan Industries and Eureka Forbes, the decision was taken at the board level, a process that takes several months. “The cost differential between road transport and air is about four times. There was no reason for us to shift our entire load to air,” says a large customer who did not wish to be named.

And many who did try out Deccan 360 weren’t happy with the service. “Often there were delays in our orders or there would be mix-ups and the packets would be sent to wrong locations,” says a customer. Some of it was because of franchisees. Gopinath placed his bet on the profit seeking instincts of small-scale businessmen to run the service centres efficiently. That seemed to work initially. For example, Kumar says franchisees could find office space for much lower rentals than what would have been possible for Deccan 360. They also knew the local market better, and recruited local talent. But soon, the same profit seeking instincts turned against the franchisees. Since they got the same amount irrespective of the distance they had to travel to deliver a package, the more remote a location, the less willing they were to do so. This affected the brand.

Blind Men and the Elephant

But franchisees have a longer list of complaints against Deccan 360. The tracking system didn’t work. Deccan 360 promised to assist franchisees in getting the business, but they didn’t do it well, or not at all. Deccan 360 kept changing the flight schedule. And worse, at times they suspended the network. The business volumes never grew as they initially suggested — and many hadn’t broken even. The payment system — which required the franchisees to deposit money with Deccan, and was adjusted against payments — was a cause of discomfort, especially when customers refused to pay citing bad service levels. “The communication from Deccan 360 was so bad, that often we had no idea what was happening,” says a franchisee.

It’s not clear if even those in Deccan 360 knew. “It was the case of the elephant and the six blind men. We had a highly capable team on the board, and they were very good in their respective areas. But they didn’t see the big picture, of how the entire system works,” says Kumar.

A series of such unfortunate events turned Deccan’s scale against it. Its strength became its weakness. “What you see in Deccan 360 is more than 32 tonnes of capacity to be filled every night and the problem comes when you don’t have enough business to fill that capacity” says Tushar Jani, founder of Blue Dart.

What must hurt Gopinath even more is that his team that was executing the plan was absolutely top-notch. From the outset, Gopinath was clear that he needed a professional team which understood the logistics business. This was unlike his approach in Air Deccan where, for a long time, he ran the operations himself. He went after the best companies — DHL, Blue Dart and FedEx — to hire his senior leadership team. In many cases he paid a premium of about 45-50 percent to get them on board. He would often boast that the combined team had an experience totalling 100 man years in the logistics business. But his team of professionals could not survive the rigours of a chaotic start-up environment. After his first CEO Jude Fonseka left in early 2010, Gopinath tried a co-CEO model. He brought in Thomas Mathew from UPS to run the logistics business and H.L. Rikhye to run the aviation business. That model too didn’t work. Mathew left the company in April this year.

Now the knives are out for the Captain. There are people who believe that Gopinath’s ambitions far exceeded his execution capability. Gopinath’s detractors say it is time to write the obituary for Deccan 360. They see Gopinath as a failed entrepreneur who comes up with good ideas which he is not able to sustain. He created India’s first low cost airline, but almost ran it down to the ground, before it was bought out by Vijay Mallya.

Shrink to Survive

His supporters on the other hand say that he is a visionary, who dreams up big ideas, but is often let down by investors who do not support him till the end. Like Air Deccan, they believe Deccan 360 is a revolutionary idea which, given some time, can become a viable business.

Amongst all the bad news, the only good news is that demand may be picking up. This year the company is expected to touch revenues of Rs. 200 crore.

Under new CEO Rikhye, an airlines professional with over 30 years of experience, a massive clean up operation is underway. Rikhye, who unlike Gopinath, tends to speak in a slow and measured tone, and to take a pragmatic, rather than an idealistic approach to the task at hand, says his focus is now on restructuring the business.

It was his idea, he says, to suspend operations, because the company was not able to live up to the delivery targets or to respond to customers. “Obviously, everybody only thought of repercussions. But I felt, unless you take a hard step and swallow your pride, it will not get corrected.”

His broad plan is to scale operations down to manageable proportions, and then gradually build it up. The immediate priority is to stem the haemorrhage — by closing down non-profitable routes, reducing capacity and also cutting down on number of cities serviced.

Kumar says that the company has two lines of credit still available and the banks will release Rs. 15 crore to Rs. 20 crore to get the operations going. In the next six months, if Captain Gopinath finds an investor, this can be taken care of. Rikhye says that he has been assured by Reliance and Gopinath that funds will not be an issue. He says operations are set to resume from May 16. Maybe Gopinath can still pull it off even if he has to shrink to survive.

In the novel, the old man finally returns to the shore, but with the skeleton of a huge fish, half-eaten by sharks. Still, generations of readers have been inspired by the scale of his ambition and the nobility of his effort. And what beat you, he thought. “Nothing,” he said aloud. “I went out too far.”

(Inputs from Nilofer D’Souza & Cuckoo Paul)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)