Unilever's buyback coup

Five years on, Hindustan Unilever's gambit to purchase its shares from Indian holders has worked well for both the company as well as investors who surrendered their stock

Unilever’s office built over old factory buildings in Rotterdam, Netherlands

Unilever’s office built over old factory buildings in Rotterdam, Netherlands

Image: Geography Photos / UIG Via Getty Images

If a CEO had a $5-billion war chest, chances are he’d probably buy back his own stock. It’s a route several companies, including Unilever, have taken in the past few years. But in the summer of 2013, Unilever CEO Paul Polman decided to adopt a circuitous route to boost earnings —he bought stock in its Indian subsidiary Hindustan Unilever. His bet was long-term growth in emerging markets would deliver superior earnings per share in the long run.

Few could have argued with his logic. In the early part of this decade, Indian consumer goods companies were on a roll. Increased rural spending mainly on account of the employment guarantee scheme had contributed to double digit volume growth. Their urban counterparts were uptrading to more expensive varieties of soaps and shampoos. The net result: A steady 20 percent annual growth in top line and a concomitant growth in bottom line.

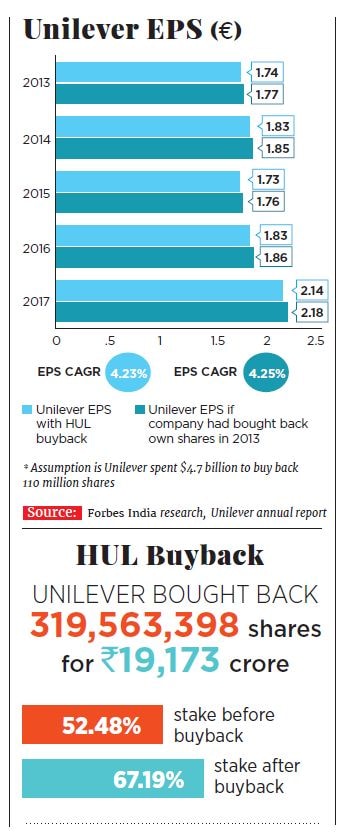

Unilever owned 52.48 percent of Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL). Developing markets contributed 55 percent of Unilever’s sales in 2013. Having lost out to rival Procter & Gamble in China, the company found itself mostly shut out of that market. Next in line was India which contributed 8 percent of Unilever’s sales.

In a May 2013 story (Unilever's Bargain Offer: Should You Hold On or Tender Your Shares?), Forbes India had argued that while it made perfect sense for Unilever to up its stake, it was also a good idea for minority shareholders to surrender their stock. India’s fast growing economy has quality businesses that were then available at reasonable prices. We argued that investors were better off hitching a ride with them.

A significant portion of minority shareholders believed it best to stick with HUL. By July 2013, its shareholders surrendered just under 32 crore shares, taking Unilever’s stake in HUL to 67.26 percent, well below the 75 percent it aimed for. Large minority shareholders like Life Insurance Corporation of India and investor Ramesh Damani refused to turn in their stock.

Five years later where do both parties stand? Would Unilever have been better off buying its own shares instead? And how have Indian consumers who decided to stay on done? “If one were to look back, it has worked well for both parties,” says Rajeev Thakkar, chief investment officer, PPFAS, a mutual fund. It is one of those rare deals where everyone comes out looking good but for different reasons.

Unilever’s Pie

Soon after he took over as Unilever boss in 2009, Polman made a decisive break from the past. Earnings guidance was out and he emphasised that he aimed to run the business with a long-term lens. He laid emphasis on volume growth and put in €80 billion in top line target—a stretch number that was put in to inculcate a culture of growth. (Unilever ended 2017 with €53.7 billion in revenue.)

In the interim, the company has divested businesses—most notably its spreads business—and fended off an unsolicited takeover bid from Brazilian buyout firm 3G Capital. This has prompted it to institute a regular buyback programme starting 2017. It has retired preference shares that gave owners 23 percent votes with just 1 percent of outstanding share capital.

What if Unilever had used that same money to buy back its own shares in 2013? The company could have extinguished 110 million shares with a $4.7 billion buyback. A Forbes India analysis shows that both scenarios would have been more or less even for Unilever. Unilever’s EPS CAGR with the buyback would have been 4.25 percent versus the 4.23 percent with the HUL buyback. Thus, it’s fair to say Unilever made the right call. This despite the fact that it paid a premium for a business where it already had operational control.

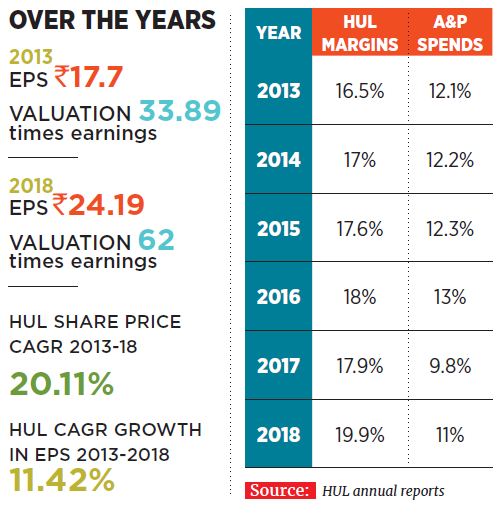

HUL has in the last five years maintained its positioning as India’s pre-eminent consumer goods company. In a country where two-thirds of the population lives in rural areas, it has trebled its rural distribution. It has successfully fended off the challenge from homegrown Patanjali and launched its own range of ayurvedic products. While competitive intensity has increased (advertising and promotion spends are 11 percent of sales), margins have risen to 19.9 percent from 16.5 percent.

On the other hand, it is also true that Unilever’s growth assumptions for the Indian market haven’t quite worked out. At ₹600 a share using the discounted cash flow formula, it likely assumed a long-term 18 percent growth in profit. That hasn’t materialised so far. But what’s interesting is that while growth across the board for consumer companies slowed, the share prices of these companies have risen faster than profits. In HUL’s case, while profits between 2013 and 2018 rose by 11.4 percent a year, its share price growth was 20.1 percent a year. HUL has also outperformed the Nifty FMCG Index which has compounded by 12.2 percent in the same period.

Lastly, HUL’s valuation multiples have expanded from 42 to 60. Thakkar believes that as growth in other parts of the economy kicks in, the performance of Indian consumer stocks will be mediocre from here on.

For minority shareholders the exit logic was equally strong. Was it possible for them to invest in companies that grew faster than 18 percent a year? Forbes India had argued that it was possible and it was a good time to switch to faster growth businesses. While we didn’t account for the slowdown in sales starting 2014, the effects of demonetisation and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax, which slowed growth, we also didn’t factor that the valuation multiples for the Indian consumer basket would continue to expand.

A key reason for this was the fall in global commodity prices. As a result, while top line growth was muted, the bottom line held up. As commodity prices rise, it remains to be seen how much growth the company is willing to sacrifice to protect margins. So while shareholders who didn’t surrender may still be able to pat themselves on the back, growth has come more on account of valuation multiples than on profit growth.

What about those who sold? In the last five years, HUL has underperformed its peers. The top five consumer goods companies barring Dabur have seen their shares appreciate faster. A range of other sectors from metals to auto and financials to agriculture related companies have outperformed. On aggregate mid-caps have done better than their larger counterparts.

A key risk for organised consumer goods businesses remains the expansion of modern retail. At about 12 percent of the $600-billion Indian retail pie, organised retail chains have seen a few skirmishes with the likes of HUL. Both sides argue that they deserve a higher share of margin and want to see lower prices for the consumer. Regional brands like Ghadi and CavinKare continue to power ahead from a lower base. There has been no let up in advertising and promotion expenses for the likes of HUL and Nestlé India. This time, investors betting on valuations rising faster than growth may run into a wall.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)