Should P&G and Unilever Merge?

A merger between P&G and Unilever doesn't make business sense

Let’s not lose market share even if it means sacrificing margins in the short term. Long Procter and Gamble’s battle cry, in the last few years it had increasingly become an intrinsic part of arch-rival Unilever’s strategy as well. Hardly surprising, as Paul Polman who became Unilever CEO in 2009 had spent 27 years at P&G.

With mergers and acquisitions picking up globally, it was only a matter of time before someone started speculating about these two behemoths. On June 2, a Daily Mail story did just that. The Mail said P&G was lining up a $62 billion bid for rival Unilever. Both companies have maintained a steadfast silence. But the question still remains: Is it a good move, or one that could destroy both companies? First off, the merger would be a step back for both companies.

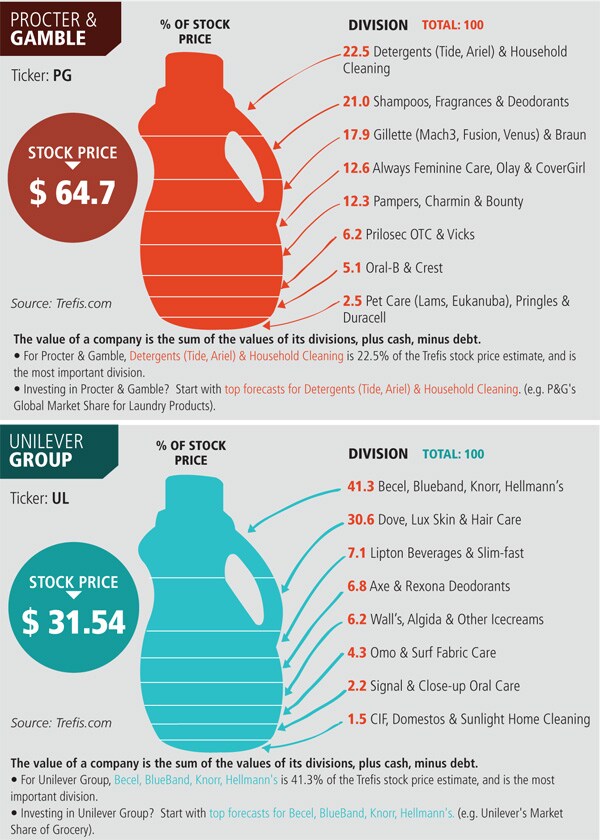

In the last decade they’ve both become leaner organisations. While both may be consumer goods companies P&G focusses more on its health and wellness business and Unilever is big on food. To merge and acquire the very same businesses they sold in the last decade does not make for good business. Then there are areas where the product overlap is so strong, particularly in the detergent segment, that it is almost certain to fall afoul of competition laws. Regulators in Europe and America have been particularly careful in approving mergers that are likely to reduce competition. Both companies will also struggle when it comes to human resources. P&G is known for its centralised decision making. Unilever on the other hand has been known for empowering local managements.

Perhaps the strongest case against a merger comes out of India and China. Both are growth markets for the companies with Unilever being strong in India and P&G being strong in China. In India, industry watchers are unsure how much smarter the two companies could get about, say sourcing, for instance. “Both companies are already large enough to get good deals from suppliers. After a point, size stops getting you lower prices,” says Shirish Pardeshi, co-head of research senior analyst at Anand Rahti.

Lastly, with the threat of competition laws, no one believes the companies would want to take on the hassle. “If you take a 20-year timeline the merger might make sense but unless you show benefits in the next three or four years the shareholders won’t be happy,” says Nirmalya Kumar, professor of marketing at the London Business School.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)