Indian ecommerce bandwagon: (More) Big shopping days ahead

As Amazon, Walmart and Alibaba gear up to shape both online and offline retail in the next decade, the capital-guzzling, deep-in-red Indian ecommerce bandwagon may have little option but to join the checkout queue

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur“An Indian ecommerce venture, profitable and sustainable, will remain a mirage for years to come.”

Days after Walmart announced its $16 billion buyout of a 77 percent stake in Flipkart, the rather grim prognosis was the candid view of the founder of one of India’s largest internet companies that’s a leader in the industry it operates in. The founder who spoke to Forbes India on the condition of anonymity then went on to point out a truism that none of his tribe will say on the record: That for most ecommerce entrepreneurs chasing valuations remains the prime objective.

There’s little gainsaying that initial reactions to Walmart’s buyout of Flipkart, in early May, bordered on the euphoric. As congratulatory messages to the founders Sachin and Binny Bansal poured in, the most commonly heard phrase was ‘watershed moment’. Homegrown entrepreneurs celebrated one of their own hitting pay dirt. Clearly this was the coming out party Indian ecommerce had been waiting a long time for.

But scarcely had the dust settled on the Flipkart deal when those same homegrown entrepreneurs, and the investors backing them, began to ponder the inevitable question. What is the road ahead for their businesses and how long before a viable model emerges for Indian ecommerce?

Image: Mexy Xavier

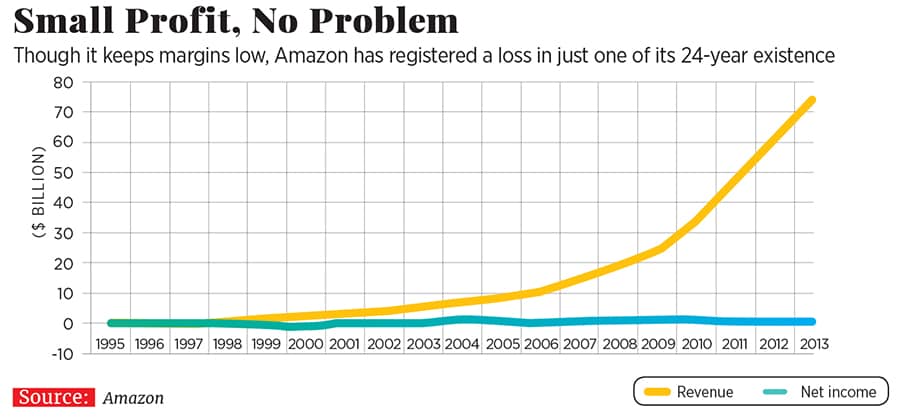

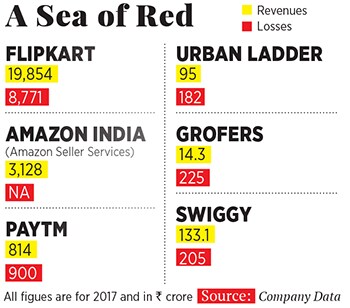

For clues, turn to the very acquisition that the Indian startup ecosystem is celebrating. In 2017, Flipkart registered an impressive 29 percent increase in its sales, or gross merchandise value (GMV), to ₹19,854 crore while losing ₹8,771 crore. In an investor presentation its new parent Walmart all but admitted that they expect losses to mount further to ₹11,500 crore in 2020 as the company battles it out with arch-rival Amazon and Alibaba-owned Paytm. On the day the deal was announced nervous investors in the United States shaved $10 billion off Walmart’s market cap.

And herein lies the dichotomy at the heart of many ecommerce ventures. India with its 200 million plus addressable internet consumers is among the largest markets in the world after the US and China. It’s enough for the three main actors Amazon, Walmart and Alibaba, with its 55 percent stake in Paytm Mall, to dig in for the long haul.

Still, for now at least, getting to those consumers is an expensive proposition—order sizes are low and delivering and collecting cash involves expensive logistics. Add returned orders (26 percent of total), and the reverse logistics are equally challenging. Online companies believe that what they lose with touch and feel, they can make up with discounts leading to high levels of cash burn for the foreseeable future. That number (losses) is estimated at ₹27,000 crore.

What’s clear is that the rules of the game are bound to change with the battle being fought entirely with foreign capital. Kashyap Deorah, author of The Golden Tap, a book on Indian ecommerce, believes unlike China and the US, India will not be a winner-takes-all market. Instead he argues that growth will be slower than projected and “the Indian market will remain far more fragmented”. It’s also the only market in the world where the world’s three biggest retailers Amazon, Alibaba (through Paytm) and Walmart compete head on and fight for a pie of the estimated $200 billion ecommerce market by 2027.