Testing company Kilpest: Valuing a sudden bump in profitability

An unexpected and extraordinary development at Kilpest left investors grappling with a question: How does one value an extraordinary surge in profits?

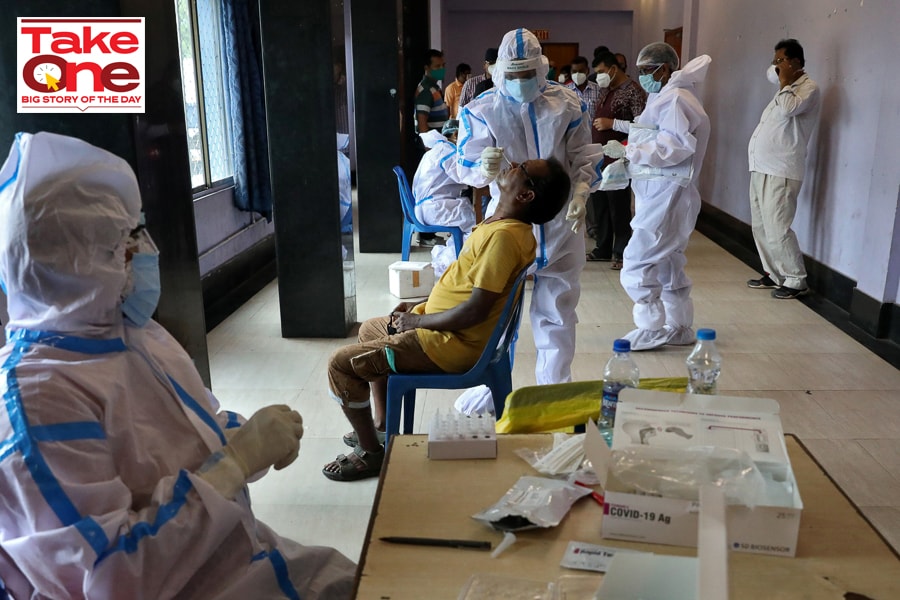

A healthcare worker wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) takes a swab sample from a man for a rapid antigen test at a check-up centre, amidst the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Kolkata, India, July 30, 2020.

A healthcare worker wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) takes a swab sample from a man for a rapid antigen test at a check-up centre, amidst the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Kolkata, India, July 30, 2020.

Photos by Rupak De Chowdhuri / Reuters

As the Covid-19 lockdowns began, and investors rushed for exits, Kilpest India’s stock held steady. It saw little erosion in value during March, and through April and May there were more buyers than sellers on most days.

The company had stumbled upon a rare opportunity and had moved quickly to make the most of it: Its RT-PCR kits, which test for the Covid-19 virus, were in high demand, and Kilpest was the only listed player that could capitalise on the opportunity. A business that had never made more than Rs 10 crore in annual profit over the last decade was now on track to end the year with Rs 100 crore in profit. (It has delivered Rs 76 crore in the first two quarters of this fiscal.) As investors rushed in, its market cap soared fivefold to Rs 550 crore in August.

But this sudden, unexpected and extraordinary development left investors grappling with a question that has come up several times over the past decade: How does one value an extraordinary surge in profits?

Past examples—there are several, such as SAIL, Rain Industries, Graphite India, HEG, Vikas WSP—have shown that in the short term, markets almost always err in according too high a multiple to the cash that has come into a business. They start pricing in the good times continuing for longer than they do. As profits rise investors rush in, only to be disappointed as the management misallocates capital and the profits eventually prove unsustainable.

“If you are a conservative investor, it makes sense to be wary,” says Sanjay Bakshi, professor at Management Development Institute, Gurugram. Bakshi, who has studied this phenomenon, points to the fact that according too high a multiple to what could essentially be a one-time infusion of cash is wrong. For instance, if a business were to receive money on account of the sale of land, the market would rarely accord that cash a high multiple.

Almost always in cases that have seen a sudden one-time surge in profitability, the managements have not been able to effectively deploy the capital. In the case of HEG and Graphite India, the managements didn’t even pay down debt fully. Instead, they chose to reward shareholders with hefty dividends. SAIL expanded capacity at the top of the steel cycle. As a result, valuations went back to levels that they were at before this one-time event. A good rule to remember is that it is best to exit these businesses at a low PE multiple.

Almost always in cases that have seen a sudden one-time surge in profitability, the managements have not been able to effectively deploy the capital. In the case of HEG and Graphite India, the managements didn’t even pay down debt fully. Instead, they chose to reward shareholders with hefty dividends. SAIL expanded capacity at the top of the steel cycle. As a result, valuations went back to levels that they were at before this one-time event. A good rule to remember is that it is best to exit these businesses at a low PE multiple.