- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- How rainmaker Sanjiv Mehta is building up HUL for the next decade

How rainmaker Sanjiv Mehta is building up HUL for the next decade

As it comes out of a long period of steady and sustained growth, India's largest FMCG company has put in place the building blocks for the next decade

After studying law I vectored towards journalism by accident and it's the only job I've done since. It's a job that has taken me on a private jet to Jaisalmer - where I wrote India's first feature on fractional ownership of business jets - to the badlands of west UP where India's sugar economy is inextricably now tied to politics. I'm a big fan of new business models and crafty entrepreneurs. Fortunately for me, there are plenty of those in Asia at the moment.

"Our share price journey is not dissimilar to those of the tech stocks in the US," says Sanjiv Mehta, MD and CEO, Hindustan Unilever. Image: Mexy Xavier

"Our share price journey is not dissimilar to those of the tech stocks in the US," says Sanjiv Mehta, MD and CEO, Hindustan Unilever. Image: Mexy Xavier

In my half dozen meetings with Sanjiv Mehta, he’s always got down to talking about his growth agenda quickly. This meeting in early July at the company headquarters is no different.

The 61-year-old boss of Hindustan Unilever (HUL) is in an expansive mood and we go through his victories from his time in the Philippines, Bangladesh, and the Middle East. In 2007, he’d taken over the Philippines operations of Unilever only to discover that the business was absent from a critical part of the haircare market—anti-dandruff shampoos. The field had been left open for competitor Procter & Gamble (P&G), which had a free run of the market. “This was unacceptable,” says Mehta.

Related stories

He needed a plan (and money) to launch a full-fledged assault on P&G’s Head & Shoulders shampoo. He decided to go all out and launch a blitzkrieg campaign. But global budgets were tight and his then-boss Harish Manwani said he could spare only a portion of what Mehta had asked for. Unwilling to get into this battle without full support, Mehta diverted funds from his local business.

The bet paid off and was to go down in Unilever’s marketing lore.

As Mehta describes it, “this was a magnificent marketing battle in every way—communication, marketing, decibel levels”. One day, there was no Clear anti-dandruff shampoo. Overnight 4,000 employees were pressed into the task of making sure it reached the length and breadth of the country. Backed by advertising, the product began to gain market share. So much so that by December of 2007, Unilever, which started the battle 10 percentage points behind P&G, had dethroned it as the leader in the shampoo business.

In every job, Mehta left signature victories as he moved on to bigger roles. He’s known in the industry as someone who, while managing the quarter-on-quarter numbers, is always on the lookout for the next big idea. It was experiences like this that ultimately proved instructive for Mehta when he took over the top job at HUL in October 2013.

In every job, Mehta left signature victories as he moved on to bigger roles. He’s known in the industry as someone who, while managing the quarter-on-quarter numbers, is always on the lookout for the next big idea. It was experiences like this that ultimately proved instructive for Mehta when he took over the top job at HUL in October 2013.

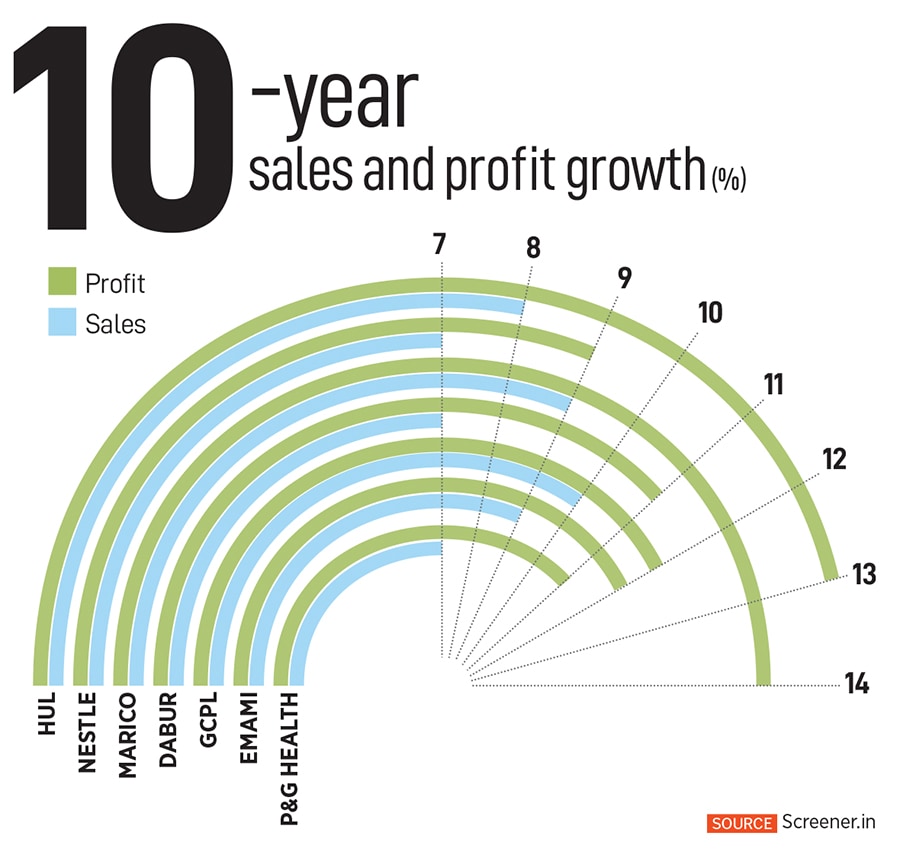

India’s largest fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company had come out of an almost decade-long slump in the 2000s. Revenues in the five years to 2013 had grown by 12 percent and profits at 13 percent a year. It had embarked on an ambitious expansion that would treble rural direct distribution reach. A few months earlier, in May 2013, parent Unilever had given a thumbs up and put down $5.4 billion in a buyback offer that took its stake to 67.25 percent.

But there was still work to be done. “You are dilutive to margins from a Unilever perspective,” was the clear message Mehta had received from his boss at Unilever, Paul Polman. In a business that has both strong global as well as homegrown Indian brands, every percentage point of market share is keenly contested. Polman wanted the company to be more competitive, that is improve market shares and be made future-ready.

HUL’s answer was to break India into 15 clusters from the earlier four and pursue tailor-made growth strategies for each. This came from Mehta’s extensive travels. Christened ‘Winning in Many Indias (WIMI)’, teams in the South would work on moving consumers from washing powder to liquids, while teams in the North moved from converting them from bars to powder. Marketing campaigns were decentralised and personnel moved to smaller cities such as Bhopal, Lucknow and Indore. In effect they were made CEOs of their regions.

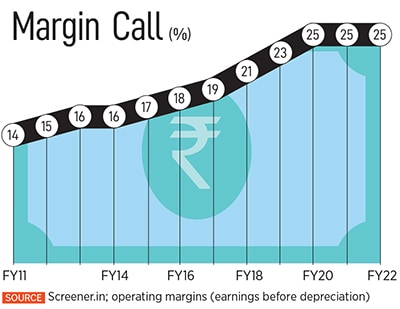

The results are plain to see. Nine years on, HUL’s revenues have doubled, Ebidta trebled and market cap quadrupled. Its margins at 23 to 24.5 percent are higher than Unilever’s 18 percent (Ebit) and have expanded by 100 bps every year. While the US remains the top Unilever market from a revenue perspective, India is the largest on the volume front. Importantly, as WIMI demonstrated, the company hasn’t slowed down even as it has grown to ₹50,000 crore in topline. It has also managed disruptions like demonetisation, the implementation of Goods & Services Tax (GST), the 2019 slowdown in rural sales as well as the Covid-19 outbreak. “Scale is not the enemy of growth. It is the ability to adapt that is more important,” says Jay Desai, managing director of Universal Consulting, pointing out that WIMI has shown the company can adapt.

HUL’s sales are up by 8 percent (on account of low inflation that resulted in sticker prices moving up slowly, compared to 2008-13) and profits 13 percent a year in the last decade, and compare favourably with competitors. Market shares across categories have improved. HUL ranks as India’s fifth most valuable company, with a market cap of ₹609,000 crore.

With margins up and the company more competitive, Mehta is now working on HUL’s ‘ability to adapt’ to keep a vast and unwieldy organisation primed for growth. A key part of the plan involves a rewiring of the distribution architecture, allowing them to go direct-to-retailers as well as direct-to-consumers (D2C) in some cases. Small experiments in the D2C space have resulted in websites—Simple and Love Beauty and Planet—that ship D2C. The company is working hard at establishing a D2C foothold in a market that is estimated at $1.9 billion by Technopak.

Then there’s the use of data to take decisions and evolve strategies. Christened ‘Livewire and Jarvis’, the data platform has been live since 2015, but it is only now showing signs of becoming a true edge in the marketplace. And lastly, there’s the speeding up of the innovation cycle that allows it to compete more effectively with faster, nimbler FMCG companies.

Controlling distribution

An hour from Chennai, in the town of Periyapalayam, the outline of a vast new project is taking shape. Here, in an industrial park shared with the likes of Flipkart and Honda Motorcycle, the Samadhan centre is located in a 450,000 sq ft warehouse and is beginning to have an impact on the way the company distributes its products.

The 28,000 kiranas dispersed in the Chennai metropolitan region would earlier be served through the distributor network. Depending on the size of the outlet, a distributor employee would visit the outlet either daily or once in a few days to collect orders and have them delivered during his next visit. These distributors were crucial to the company as they were its eyes and ears on the ground. They also extended credit to the kirana network.

The 28,000 kiranas dispersed in the Chennai metropolitan region would earlier be served through the distributor network. Depending on the size of the outlet, a distributor employee would visit the outlet either daily or once in a few days to collect orders and have them delivered during his next visit. These distributors were crucial to the company as they were its eyes and ears on the ground. They also extended credit to the kirana network.

The initial iteration of modern trade in India did not pose too much of a threat to established FMCG companies. Sure, there were some disputes, with the most prominent example being the now-bankrupt Future Group pulling Kellogg’s cereals from their shelves over a margin dispute. But, in general, modern trade was too small to pose a threat to the established cost structures of HUL. Instead, the company chose to extend its reach in rural India.

This changed, starting 2015, when large business-to-business (B2B) retailers—Reliance Retail, Flipkart Wholesale, Metro Cash & Carry, Udaan—started taking away market share. At the same time, implementation of GST saw traditional wholesale channels suffer. Large FMCG companies could see the writing on the wall. S Muthu of Chinamani Agencies, a Chennai-based distributor, admits that at times, the kiranas he serves would prefer to take supplies from Udaan due to the promotions they run. “It [HUL] realised that once these delivery models get sticky, it will end up losing power with the consumer,” says Amit Khurana, head of research at Dolat Capital.

Also read: Traditional trade's resilience in the era of instant gratification

There is also an inherent limitation with the distributor model. As the size and scale of operations increase, the distributor has to stock more products, employ more capital and have more boots on the ground. Few have the ability to scale up. “If you go to a distributor today, I have to admit, they struggle with the tail of the portfolio. To make sure they serve the kiranas with these is difficult,” says Willem Uijen, executive director, supply chain at HUL.

HUL’s answer was to deploy a tech-heavy solution. All orders are served directly from the company warehouse. Kiranas are promised next-day delivery with no minimum order. They can order just one 50 gm tube of Closeup toothpaste each day and it will be served. Clearly, for the company, no sale is too small to lose and kiranas are comfortable stocking just as much as they need.

In return, the company gets ground-level granular data of what is selling, how much and where. This allows HUL to maintain control over 80 percent of its sales sold through general trade. (HUL says 20 percent of sales comes from the digital channel, which includes ecommerce, modern trade as well as orders taken on its own Shikhar app.) It would have tighter control over promotions, customer development, new launches and new SKUs (stock keeping units). Absent this, it would end up conceding control to large wholesale retailers and in time weakening its bargaining power with them.

Distributors have had their roles rewired to collecting orders, collecting payments and extending credit to shop owners. They don’t stock inventory anymore. Muthu of Chintamani Agencies sends his team of 14 employees to collect orders every day. By 3 pm, the information is relayed to the company through their handheld devices and his job is to extend 14 days’ credit. On his part, he still gets to maintain an 18 percent return on investment without the need to block his capital in inventory. Kirana owners are also blocking less capital and have the confidence that their orders will be served the next day.

Khurana estimates that HUL’s larger rivals are almost sure to follow its lead, but would be constrained with the size of their portfolio, which would make daily direct distribution beyond a point unviable. Smaller companies with weaker brands would eventually end up ceding ground to ecommerce and modern trade.

Since late 2019, HUL has spent time perfecting the technology behind the Samadhan centre. Order information is relayed along a conveyor belt, as pickers put in everything from soaps and shampoos to detergents and food products in pre-labelled boxes. They are then sent to a stacking system where they wait for their chance to be loaded on to trucks along a pre-determined route. Over the last two years, Pratik Kejriwal, who heads the fulfillment operation for South India, estimates they’ve made a dozen iterations to the software to make sure it runs smoothly. “We now plan to take Samadhan to metros across the country over the next two years,” says Uijen.

Reams of data (and analysis)

If Samadhan is ‘Exhibit A’ in making HUL future-fit, its digitisation journey is arguably as important. It also provides an insight into how technologically heavy companies have become, as well as the power of data in making business decisions.

Starting 2015, the company moved to get comfortable with the reams of data its business units generated. While there was a lot of information within business units on trade promotions, media spends and competitive intensity, it hadn’t been put into a system that was accessible to all. “What we ended up doing was democratise the use of this data,” says Arun Neelkantan, vice president, digital transformation and growth at HUL.

Christened ‘Project Livewire’, the first three years were spent getting comfortable with data and running hundreds of experiments. This gave rise to the Shikhar app where today 8 lakh retailers enter orders online. It allows the company to witness a demand slowdown or surge (as in the case of hand sanitisers during the Covid-19 pandemic) in real time.

Christened ‘Project Livewire’, the first three years were spent getting comfortable with data and running hundreds of experiments. This gave rise to the Shikhar app where today 8 lakh retailers enter orders online. It allows the company to witness a demand slowdown or surge (as in the case of hand sanitisers during the Covid-19 pandemic) in real time.

Stabilising data is a mammoth task and there is also the challenge of what to do with it. Data massaging and parsing have a lot of techniques, starting from a simple Excel sheet where one can look for outliers and correlations. There’s the Bayesian framework, where the number of input items can impact the outcome. There’s narrow artificial intelligence (AI), where banks look for outliers to help them with fraud detection; and there’s wide AI, where companies like Google and Tesla are working on driverless cars.

Neelkantan explains that the company spent three years figuring out what works. One cannot tinker with the data sets too often as that would impact the output and make it harder to study causality. The company is now confident that this system has been through enough repetitions for the data to be relevant across a wide variety of business decisions. This would eliminate decisions taken on gut feel.

“We are finally moving from diagnostic to predictive and prescriptive,” says Mehta, pointing out that the possibilities that this results in are immense. Data sets would allow the company to look for causality between, say, increased media spends and sales. In certain areas, advertising in the afternoon on regional channels would work better; in others, spending on trade promotions would work better. If this was earlier done at a state level, it can now be done at the district level. Areas with similar socioeconomic profiles will behave similarly and the company can decide what products to push there.

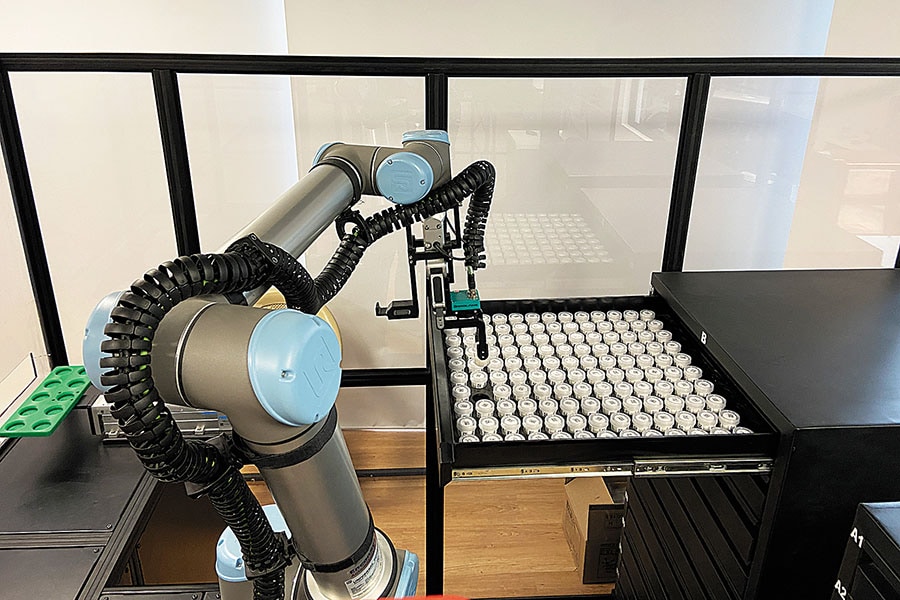

A robot-assisted perfume laboratory provides access to multiple fragrances

A robot-assisted perfume laboratory provides access to multiple fragrances

Brand managers could craft marketing strategies for similarly placed districts in a state or region. They would be able to access data on piped water connections or Ujjwala gas beneficiaries while deciding on trade promotion spends. In some areas, they may decide to go slow on low unit packs—₹1, ₹2, ₹5 and ₹10 that make up 30 percent of sales—while others could see the launch of bridge packs to hold on to market share.

While decisions like these would earlier be taken in silos, learnings are now visible for the entire organisation at the click of a button. Neelkantan estimates that this has given a 2 percent annual uptick in sales and probably explains why HUL is able to tap into multiple micro-growth levers even when the rest of the industry slows.

Small batch manufacturing

While most of HUL still thinks in tonnes or 1000s of kilogrammes, there is a small part of the company that is getting comfortable working with kilogrammes. As consumer markets get disaggregated, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to satisfy the consumer of the future. A housewife might prefer her dishwashing soap in a certain fragrance ordered directly from the company, while a teenager might want a face mask with a mineral that can only be made in smaller batches.

Also read: Juicy, Sugar and Wow: How three families are giving India's FMCG giants a run for their money

This is a challenge FMCG companies the world over are preparing to address. India has seen the rise of smaller D2C brands that have scaled up rapidly. Take, for instance, Honasa Consumer, the parent company of Mamaearth. It doubled its revenue from ₹460 crore in FY21 to ₹960 crore in FY22 and entered the unicorn club. Shampoos and skincare products now cater to niches that larger competitors are often absent in. Normally HUL would talk in terms of 5,000 kg or 10,000 kg, but now a batch size of 250 kg is possible, says Uijen. This is partly because large established companies like Unilever have worked on the premise that bulk manufacturing is cheaper. The rise of national television networks allowed for advertising to aggregate demand and benefit from economies of scale. Now, as consumers become more individualistic about their products, these companies have been pushed to respond to this shift.

Advertising for new challenger brands is online instead of mass campaigns, as they are loath to concede these markets to small, more nimble, custom manufacturers. This requires a reconfiguration in the way they operate. It’s still early days and while HUL doesn’t break out its D2C numbers, a run rate of ₹100 crore a month is what they are aiming at, according to industry sources.

HUL now has several challenger brands in the D2C space: Dove Baby, Love Beauty and Planet, Simple, Dermalogica and Lakme. Others like Indulekha also have standalone websites where consumers can order from. It is also a global push from Unilever, which saw ecommerce sales move to 9 percent during the pandemic and has acquired online-only brands like Dollar Shave Club that helped it learn more about shipping D2C.

A key part of working directly with consumers is shortening the product development cycle. In the past, a new product would take six to 12 months from concept to market. The research team and supply chain have crunched this to 70 to 100 days.

To understand how this works, step inside HUL’s AI lab in Mumbai, Bengaluru or Gurugram. Here, the company picks up signals on what consumers are searching for, from trade data as well as search terms on the internet. In 2019-20, the company saw a threefold increase in search for rice water shampoo—a segment it had no presence in. Two brands, Mamaearth and Buds and Berries, had split the market between themselves.

A team at the headquarters got cracking. The first step was to see if the product was available in Unilever’s global repertoire. It was. Unilever sold rice water shampoo in 21 countries. With the click of a button, HUL was able to study price points, ingredients, durability, consumer feedback and acceptability.

An onsite perfume laboratory provided access to 3,000 fragrances. 3D printers worked on the packaging. Always-on consumer panels provided feedback within a week. (The company takes temporary approvals to ship products to consumers for feedback.) “In all, we were able to get the product to market in 72 days, which is significantly ahead of our earlier lead time,” says Vibhav R Sanzgiri, executive director, research and development at the company. He keeps a close eye on what consumers are searching for, what’s trending in other Unilever markets and what is working in ecommerce. Most of this data is available in real time. The rice water shampoo was launched under the D2C brand Love Beauty and Planet, and is available on its own website.

Manufacturing is done at one of the five nano factories that HUL has set up. These are designed to run small, custom manufacturing batches of as little as 5 kg each and can be controlled remotely. The company declined to comment on numbers for this specific rice water shampoo example, but said it is able to quickly scale up or down products with different fragrances, based on consumer acceptance. For now, the numbers of the small batch manufacturing front are small, but they show how large FMCG companies can take on nimbler competition and don’t necessarily have to vacate market niches on account of the way their manufacturing is structured.

Keeping control of consumer data, using technology to work on increasing sales and tapping into consumer niches are what make investors confident about the HUL stock.

A decade of outperformance

Mehta is justifiably proud of how the company has rewarded investors since he took over. Sure, a lot of the building blocks were put in place before 2013, but the company has shown that it can grow under all market circumstances. In the last decade, the stock has returned 18.9 percent a year to investors, outperforming the Sensex, which is up 12.8 percent a year in the same period.

HUL’s Samadhan distribution centre is located in a 450,000 sq ft warehouse in Periyapalayam, an hour from Chennai

HUL’s Samadhan distribution centre is located in a 450,000 sq ft warehouse in Periyapalayam, an hour from Chennai

“Our share price journey is not dissimilar to those of the tech stocks in the US,” says Mehta. When one accounts for the fact that unlike tech stocks, HUL’s performance comes with less volatile growth, steady cash flows and a rising earnings multiple, it is probably a better bet than Alphabet, Amazon or Microsoft, which have compounded at between 18 percent and 23 percent in the last decade.

“Investors have rewarded us for our consistent performance,” says Ritesh Tiwari, chief financial officer at HUL. Volatile numbers rarely get a high price-to-earnings multiple as it becomes that much harder to estimate future earnings. While HUL commands a multiple in excess of 60 times earnings, Unilever trades at 20 times. A part of that is on account of the longer growth runway as well as the fact that the company has not had a single year of low growth in the last decade.

But this period has also seen low food price inflation in India, and until the pandemic, commodity prices were subdued. Both those have reversed and this is something the top management is keenly aware of. HUL has been working on a 7 percent per year cost reduction target so that consumers have to face a lower sticker shock. In some markets, they have chosen to withdraw from their low unit pack price points, which make up 30 percent of sales; in others, they have reduced grammage.

There’s also a limit to which margins can expand. At 23 to 24 percent, they are already the highest in the industry (Nestlé India comes close at 22 to 23 percent), giving them limited room to grow. This Tiwari confirms has already been communicated to the market. “The value creation model will now be growth-led with modest margin expansion,” he says, while pointing out that they still hope for double digit EPS (earnings per share) growth.

There could also be opportunistic plays like the Horlicks acquisition. Unilever was able to wisely use the gains from its 2013 buyback to pay for a large chunk of the acquisition. Yet, Mehta is aware that the next decade may be harder than the previous one as inflation eats into consumer income and the commodity cycle remains elevated. “When there is a lot of breeze, even turkeys can fly, when there is no breeze... that’s when you determine who is an eagle and who is not,” he says signalling that he doesn’t disagree with the hypothesis.

“But I remain confident. Watch this space.”