Newly rechristened Tata Consumer Products goes beyond beverages

Even with solid tea, coffee and water brands, the company had seen uninspiring returns. Now, the re-invented TCP is writing a new script

Sunil D’Souza, MD & CEO of TCP, is rejigging internal structures and distribution methods

Sunil D’Souza, MD & CEO of TCP, is rejigging internal structures and distribution methodsImage: Mexy Xavier

Why are we not in the top echelons of Indian consumer businesses, was a question that resounded often within the hallowed walls of Bombay House, the headquarters of Tata Sons. The 152-year-old business house had some of the biggest consumer brands in the country across sectors—from automobiles and jewellery to consumer durables and beverages. Over the years it had shown the capability to invest in any business it wanted to. And a competent set of managers ran these businesses. Despite this, Tata Sons found itself cut off from the 50 times earnings multiples that Indian consumer companies commanded.

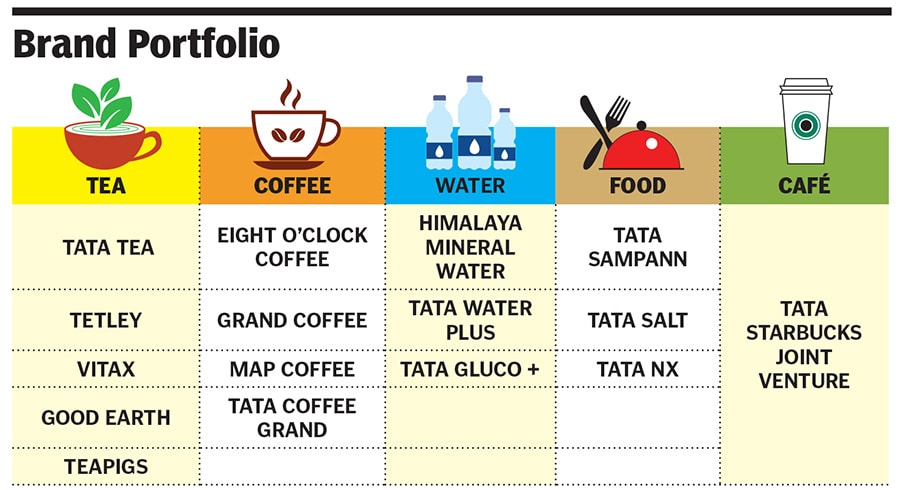

The closest it had come to a consumer business was with a company that has recently been christened Tata Consumer Products (TCP). It had a solid tea and coffee franchise—Tata Tea, Tata Coffee—as well as a premium product in Himalaya water. The global portfolio included Tetley Tea and Eight O’Clock Coffee.

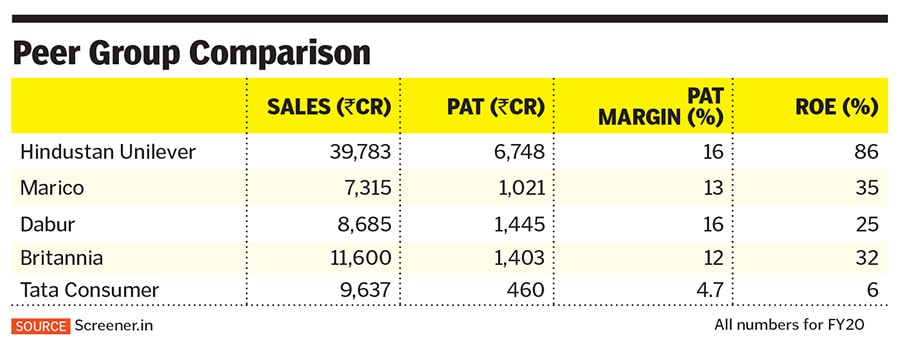

But partly on account of the price it paid for acquiring Tetley and the way its business was structured in India, its return ratios were uninspiring for fund managers to consider buying the stock. Return on equity stood at 6 percent in the year ended March 2020, compared to 86 percent for Hindustan Unilever (HUL) and 35 percent for homegrown Marico.

Operating margins were in the high teens and decadal growth rates for sales and profits were 5 and 4 percent respectively. (Voltas, another group company in the consumer durable space, also had an indifferent decade, with profits growing at 4 percent a year.) For much of the last 10 years, the market has priced it at between 15 and 20 times earnings. In short, it was hardly the premium valuation that a top business house would be happy with.

Meanwhile, between 2015 and 2020, Sunil D’Souza (53) was scripting a success story with the India operations of Whirlpool. He had an impressive résumé—he’d worked in HUL, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo in India and Southeast Asia—and industry watchers liked what he had done with Whirlpool; profits rose by 17 percent a year and revenues 13 percent.

Rahul Rathi, who runs Purnartha Investment Advisors, has known D’Souza from his time at Whirlpool. What impressed him was that the company was able to get into a negative working capital cycle for what are essentially commodity products—refrigerators, washing machines and air conditioners. This resulted in the market giving it an earnings multiple of 58 times, a rarity in this business. According to Rathi, this growth mindset often comes from the leader at the top.

With a successful stint at Whirlpool, the opportunity to write a new script at TCP was a logical challenge for D’Souza to take up. He was promised a free hand. Once the plan was in place, he was to make a presentation to the board and would be given the freedom to execute. “That was a challenge that I couldn’t refuse,” says D’Souza, who took over as MD and CEO of TCP on April 4, when the country was under lockdown. More recently, news that Tata Sons may be in the running for a stake in BigBasket shows that the group is serious about beefing up its presence in consumer businesses. Tata Sons declined to comment.

Dealing directly with retailers can give Tata Consumer Products more visibility and shelf space

Dealing directly with retailers can give Tata Consumer Products more visibility and shelf spaceBefore joining, D’Souza spent time visiting markets, understanding the company’s products, and meeting employees. His first few days were spent in getting permissions for restarting plants, making sure the procurement engine doesn’t come unstuck, and getting shelves stocked. With that out of the way, he began work on simplifying the organisation structure—with beverages, food, Nourishco (a joint venture making non-carbonated beverages that had been run with PepsiCo India and was acquired by TCP) and international businesses as prominent verticals. As a leader, he realised that getting a new structure in place would end any uncertainty among employees.

Next began work on simplifying distribution. This was important as it had the potential to allow the company to add new products as well as add to margins. With a product basket as large and diverse as TCP’s, the company faced multiple challenges here. First, it had a layer called consignee agents that most consumer companies had done away with. They typically reach stores directly through their stockists or through company employees.

While money is saved when a layer between the consumer and the company is eliminated, it also allows for faster access to market intelligence and gives companies more control over how their products are placed at stores. TCP’s basket of products was now big enough to allow for this consolidation.

Direct distribution is another key metric consumer businesses focus on. In 2010, HUL had unveiled an ambitious plan to treble its direct reach in rural India. “This increase in rural coverage will be a big leap, and to my mind, will be a huge driver of future growth,” then HUL Chairman Harish Manwani had said at its 2010 annual general meeting.

Over the next 12 months, D’Souza plans to double TCP’s direct reach from 5 lakh outlets at present; the 25 lakh outlets (overall) it reaches should double in the next 36 months. This will give the company great say over display and promotions in stores and then allow it to power its brands with advertising spends. With an integrated backend, a single truck would go for both beverages and food, compared to the different routes that are being followed at present.

With a consolidated front- and backend in place, D’Souza believes the future is “about plugging in a category and driving synergies and a better return profile as we go forward”. He hopes to save between 2 and 3 percent of topline on account of these synergies. This can then be invested in the business or moved to bolster the bottom line. How Tata Consumer performs in improving margins and increasing profitability will be key to judging his tenure.

So far, the market has given the company a resounding thumbs up. It is up by 56 percent since the news of D’souza’s appointment, taking TCP’s market cap to ₹43,000 crore. For now, its operating margins at 12 to 14 percent don’t justify this valuation. It remains to be seen how they move up and how the topline grows.

With distribution rejigged, plugging in more categories will be a key focus. A significant growth driver is likely to be the pulses business. Here D’Souza is clear he doesn’t want to play on the mass end and chase topline. Instead, premium products like unpolished pulses could provide an opportunity for the company to capitalise through the Tata Sampann brand. The business received a fillip during the lockdown when consumers showed the propensity to shift to branded products on account of quality and hygiene.

The last decade has seen various agri commodities move from unbranded to branded products. Take wheat, which now has brands like ITC Aashirvaad, or basmati rice that has Kohinoor, Daawat, India Gate or Fortune. “The smart thing they’ve done is go after a category that was ripe for picking as it is still highly fragmented,” says Devangshu Dutta, CEO of Third Eyesight, a retail consultancy. He cautions that while there is a lot of scope to cut out the middleman and keep margins in what is a thin-margin business, it is also a business that takes time to build and scale. For now, its main competition will be from regional brands.

In the tea business, moving 40 percent of consumers who drink unbranded tea to Tata brands is another focus area. With coffee, it is not a conversion opportunity but a market share gain opportunity that TCP has to work on. Salt lends itself to premiumisation. Varieties with less sodium and more iron can retail for 50 percent more than plain salt. In addition the Nourishco business, which has a ₹200 crore topline, and Tata Starbucks should also provide additional growth levers.

While India is expected to be a growth engine, it is the international business that TCP views as a steady cash generating machine, albeit one with low growth. Its Tetley brand has a strong following in the US, the UK and Canada.

It is here that TCP faces a problem. The acquisition of Tetley for $400 million (₹1,750 crore) in 2000 saddled its balance sheet with goodwill costs that currently stand at ₹7,600 crore. This line item has dragged its return on capital employed to 8.1 percent in the year ended March 2020. It’s not clear how the board manages to deal with this, but when asked whether a sale or large impairment charge was the only way to get rid of this, D’Souza clarified “goodwill is something we already have on the balance sheet and am aware that most investors calculate their return metrices with goodwill. Therefore, our endeavour is to continue to improve performance to move these metrices positively”. He added: “On a separate note, we also review our business portfolio periodically to make sure we have the right mix and will not hesitate in taking tough decisions. We have demonstrated this when we exited Russia, China and recently the Czech Republic.”

There could also be some news on the acquisition front. At ₹2,000 crore, the company has significant cash to deploy, but as several of D’Souza’s peers have learnt, a decade of high price multiples of consumer businesses has meant that these opportunities, in India at least, don’t come cheap. (He declined to comment on whether the company would be interested in HUL’s global tea business, which is up for sale.)

Returning the cash to shareholders is another option. “For any business, as long as you are firing up the topline while keeping the middle portion [fixed costs] tight, then a significant portion of the margin comes into the bottom line,” he says. D’Souza is also aware of the challenge of nurturing businesses that are in different stages of their growth cycle—a key task during his last role at PepsiCo. The market did see a glimpse of that in the first quarter earnings when net profit nearly doubled to ₹345 crore even though topline was up by only 13 percent to ₹2,746 crore. As the market waits for news on acquisitions or new product launches, increased profitability is something that will take with both hands.