Realty funds: This financial lifeline has caveats

Realty funds are making significant investments in an industry in distress. But what happens if sales don't pick up?

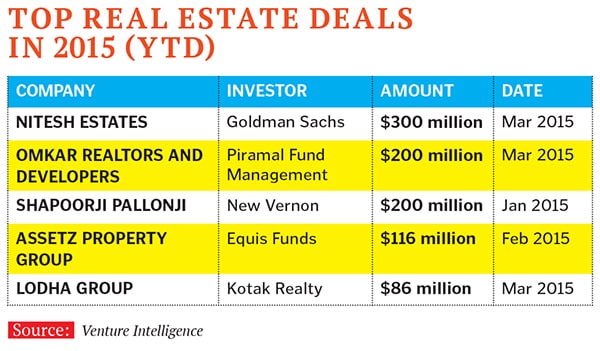

Amid the slum tenements of Worli in mid-town Mumbai, the outline of a vast project is taking shape. Across 20 million sq ft, Omkar Developers is building three residential luxury towers that promise to reshape Mumbai’s skyline. The project, christened Omkar 1973 Worli after the latitude and longitude along which Mumbai is located, recently received an investment of Rs 1,200 crore from Piramal Fund Management, promoted by billionaire Ajay Piramal.

The deal, which was sealed in March 2015, is the third time the fund has invested in the project. The first was a Rs 200 crore investment in 2010 when the builder was redeveloping a nine-acre plot of land, and had to provide housing for locals under the Slum Rehabilitation Authority scheme. Two years later, the fund pumped in an additional Rs 130 crore, which Omkar used to buy a small plot adjacent to the project. But it is the Rs 1,200 crore deal that has got the industry talking, and with good reason, too: It is a bold bet on the real estate sector at a time when sales have been, to put it mildly, not at their best levels. Data from Knight Frank says sales of residential units in the top six cities fell from 284,555 units to 234,930 units between 2014 and 2015.

With this injection of capital, Piramal Fund Management has effectively bought over 8 million sq ft of the 20 million up for sale. Half of the money has been given against future receivables and the other half can be sold by the fund at a time when it sees fit. “Omkar has achieved financial closure on the project, and we’ve got a slice of marquee real estate,” says Khushru Jijina, managing director of Piramal Fund Management. Left unsaid is that with this latest round of financing, the fund has allowed the developer to maintain prices in the current lacklustre market.

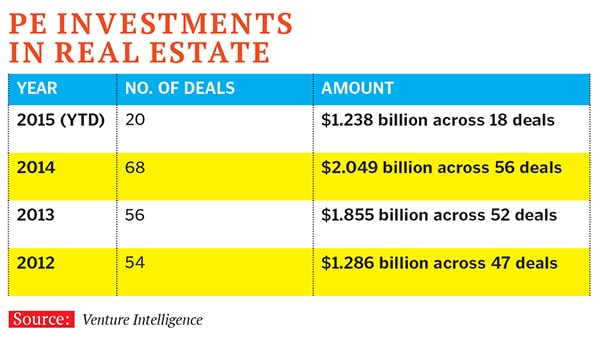

At a time when sales are slowing, private equity (PE) real estate funds are providing a lifeline to developers. Most of the two dozen fund heads that Forbes India spoke to declined to come on record when discussing the future of the business, but in piecing together their conversations, a few takeaways have emerged. A lot of money is being pumped into the industry, and newer players with lesser underwriting skills may be making optimistic projections. According to research firm Venture Intelligence, between January and December 2014, PE players invested $2.049 billion in real estate projects across the country. Since the start of 2015, $1.238 billion has already been invested. One developer even boasted that there was so much money around that he was juggling five term sheets for each of his projects.

But PE realty funds may very well cut this lifeline if sales fail to pick up. Their less-than-stellar record in the last eight years remains fresh in collective memory, and the numbers tell a sobering tale: While there is no official data, industry analysts estimate that of the 160 funds that set up shop in India after 2006, over 90 percent failed to return to their investors the principal they had invested. “It was an industry where the players clearly did not realise what they were getting into,” says Amit Bhagat, chief executive officer of ASK’s realty fund. He cites delays in getting permissions from authorities and the execution risk that a lot of developers faced as some of the reasons for their poor performance.

Many of the builders did not have the skills to ramp up their operations. Management bandwidth was stretched. As a result, many deals saw muted returns.

One of the mistakes the initial investors made in the 2006-08 period was to get into equity deals with developers. As projects stalled, funds saw their returns vanish.

Only about three dozen funds survived the upheaval, and they are walking the fine line between risk and reward. “Those that survived realised that they needed to understand the risk profile more clearly,” says Rahul Rai, executive vice president and head of ICICI Prudential AMC’s realty fund.

As a result, the industry did a U-turn, and since 2008 has undertaken only a handful of equity deals. Now, funds insist that the developer agree to a certain rate of interest (between 18 and 24 percent) with the option of a kicker if a project does well. In short, the industry is willing to sacrifice higher gains that could come from an equity investment for a more stable and assured return.

On the one hand, there are signs of innovation because funds are not constrained by many of the rules that banks and non-banking finance companies have to follow. A case in point is the realty fund set up by financial services group ASK, which has partnered with a developer to buy land. (The norm for most funds is to lend debt to under-construction projects.) In another emerging ‘innovation’, PE funds are buying entire blocks in ongoing projects.

Ambar Maheshwari, chief executive officer of Indiabulls’s first real estate fund, sees these trends as a maturing of an industry that has taken a lot of hits over the past few years. “We’ve clearly learned from past mistakes, and hopefully we will fare better with these investments,” he says.

Ramesh Jogani, managing director of India Property Advisors, puts it more bluntly. “As an industry we haven’t made significant returns for our investors,” he says. Investments made after the Lehman crisis should be better.

Since May 2014, from the time the Narendra Modi-led government was formed, sales have slowed even further. Residential real estate, which is for the most part self-financing, has been forced to borrow money as developers are unable to sell apartments fast enough for the project to pay for itself. PE has filled the gap, for now, and this has helped premium developers in sought-after areas maintain pricing. But if sales don’t pick up in the next 24 months, the industry could be staring at another set of write-offs, and may not be able to return capital to their investors.

To guard against this outcome, investing funds have assumed a much lower growth rate in prices. But even the most optimistic managers agree that they haven’t factored in a prolonged period of stagnant prices or a price correction.

It is likely that a marquee project like Omkar 1973 may sell out: There has already been an uptick in sales as the Rs 1,200 crore from Piramal Fund Management allowed Omkar to offer a 20:80 scheme where a buyer can pay 20 percent of the price and then nothing till possession. However, not all investing funds have the luxury of getting into one-of-a-kind projects (the price per sq ft is about Rs 40,000). Such projects are more an exception than the norm.

One fund manager even admitted that if the current sluggish pace of sales continues, “a lot of us will have to start looking for new jobs”.

For the realty fund business in India, the next three years will be a make-or-break situation. Failure to get it right this time around may mean that investors will be unwilling to trust developers with their money a third time.

And that is a scenario no one wants to see play out.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)