Shree Cement's Hari Mohan Bangur: On solid ground

The entrepreneur from Kolkata has all the trappings of an industry leader: He has survived tough times, innovated to grow and is bold to a fault

Forbes India Leadership Awards 2017: Entrepreneur For The Year

The inside of Hari Mohan Bangur’s office, on the banks of the Hooghly in Kolkata’s old commercial district, is marked by a lack of clutter. The desk is spotless, no computer or any other gadget to distract the 65-year-old managing director of Shree Cement as he manages his cement empire spread across northern and central India.

A firm believer in delegation, his phone also purrs only occasionally. But this is also because his plants run with clockwork precision. This can be, in large part, attributed to the fact that his employees are encouraged to share ideas. For instance, they’re told that if they don’t hear from the management in 48 hours, they should run with an idea. Also, the company has no variable pay. “Working is a reward in itself. Your peers force you to perform better. If someone is paid extra for a good idea, it means I would have to penalise someone else for a bad idea. This is not something I want to do,” says Bangur.

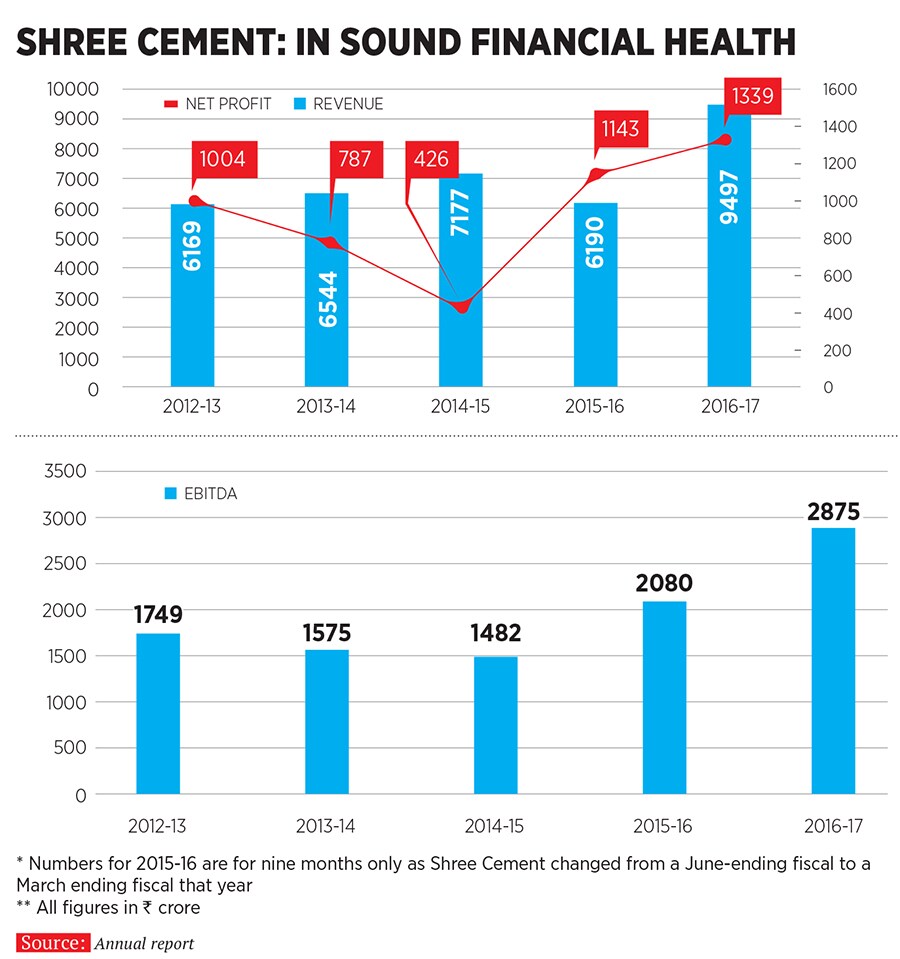

It is this measured philosophy that has allowed Shree Cement to innovate and expand capacity over 15-fold, from 1.8 million tonnes in 2000 to 28 million tonnes today. The company says it is on track to breach the 40-million tonne mark by 2020. It also has an efficient power generation business, which makes use of the steam produced during the production of cement. All this has made the company’s stock a market favourite. In the last 15 years, its share price has risen from ₹50 to ₹18,500, at a compounded growth rate of 48.3 percent, making it the best performing cement stock in India. As a result, Shree Cement’s market cap stands at around ₹64,000 crore. Prashant Jain, executive director and chief investment officer of HDFC Mutual Fund, attributes the company’s success to the culture of innovation. “They were the first to try out an alternative energy source, which enabled them to outperform their peers,” he says.

But the Shree Cement story isn’t without its share of twists and turns. In the late 1990s, struggling to cope with a particularly ferocious downcycle—when, according to son Prashant, “interest payments amounted to 12 percent of sales”—Bangur almost sold the company to Vicat, a French cement company. But even as the deal was waiting to be signed, he decided to give the business one last try.

Thereafter, as he’d admitted in a 2013 interview to Forbes India, his entrepreneurial journey has been “dream-like”. In 2016, during another interaction with the magazine, he ascribed Shree Cement’s success to “having a plan and working towards it”. And that plan has worked out so well that Bangur’s company is setting industry standards.

Tracing their lineage back to Mungee Ram, who emigrated to Kolkata in West Bengal from Didwana in Rajasthan in the early 1900s, the Bangurs were, in the 1960s, counted among the top 10 business houses in India. Their rise was in no small part powered by the boom in Indian businesses before and during World War II when Mungee Ram, Bangur’s great-grandfather, bought an old jute mill in Howrah, near Kolkata, and turned it around.

The British departure post-Independence resulted in the sale of several businesses and the family used the opportunity to enter sectors as diverse as cotton textiles and paper, and also set up a graphite factory and a cement plant. However, a series of reverses during the 1960s and ’70s resulted in the Bangurs losing their footing.

Image: Vikas Khot

They were destined to find it in cement, with which the Bangurs have had a long relationship. It goes back to early 1915 when, invited by the Maharaja of Jamnagar, the Bangur family had set up a cement plant called Digvijay Cement in Gujarat. (It has since been sold several times and is no longer with the Bangurs). While that business struggled to make money, unbeknownst to the owners, some company executives procured a licence for a cement plant in Rajasthan in the 1970s. During the Permit Raj, getting a licence was everything and while the executives received a tongue-lashing for not having taken the owners into confidence, the Bangurs decided to go ahead and set up Shree Cement, which began production in 1985.

It was in this business that Benu Gopal Bangur, chairman of Shree Cement and Bangur’s father, became actively involved.

This was also the time that Bangur was cutting his teeth in the business. His initial years were spent in diverse sectors, from cement (both Digvijay Cement and Shree Cement) to cotton and jute textiles as well as in a mattress company owned by the family. In fact, fresh out of studying chemical engineering at IIT Bombay, he went to work for his father’s cousin, Narsing Dass Bangur, who was considered the head of the Bangur empire and was Mungee Ram’s grandson. (There was an unsaid rule among the Bangurs that no one would work with their parents.)

What he learnt from the late Narsing Dass proved invaluable. “My father would always look at the micro picture—say, how they fixed a particular machine in the factory. My uncle would not bother with this… he would only look at the larger macro picture,” he says. So if demand for paper was expected to pick up, he would invest two years ahead of schedule to take advantage of the inevitable cyclical uptick.

Another important lesson Narsing Dass taught the young Bangur was that the family should not invest in any business where an agricultural product was the raw material. The logic for this was simple. During bad times, the government forced companies to pay a certain minimum amount to farmers and, during good times, it would never allow the industry to make super normal profits. “If we look at industries like sugar and jute, we realise how right he was,” says Bangur.

After working in the family business for over a decade, Bangur, along with his father, settled on cement during what can easily be described as a different era in the mid-1980s. Every aspect of the industry was regulated—from how much to produce to whom to sell how much to. The controller of cement would allot quantities—bags sold to allottees were priced at ₹60 and immediately sold in the open market at ₹160. Cement companies would even collect money two months in advance, obviating the need for working capital in the business.

In the last 15 years, Shree Cement’s share price has risen from ₹50 to ₹18,500 at a compounded growth rate of 48.3%

As the government gradually ‘decontrolled’ the cement business through the late ’80s, there was a rush to set up capacity. As a result, through the 1990s, the cement industry was saddled with overcapacity. Things started to look up for the industry after 2003 once demand recovered.

It was by way of a family settlement—there was an earlier one in 1989 to split the business among the various Bangur families—in 1998 that Benu Gopal got complete control of Shree Cement. It was then that the young Bangur found that he had his task cut out as the company had just expanded capacity at Shree Cement’s Beawar, Rajasthan, plant from 180,000 tonnes to 600,000 tonnes. Unfortunately for Bangur, he caught the lowest point of the cement cycle. “After we expanded, the market became very bad and the company lost a lot of money as demand tanked as the cash was converted to assets,” he recalls.

Unsure of what to do with the business, Bangur decided to shop for a buyer. French cement major Vicat was looking for an entry into India and agreed to get into a deal with Bangur. The plan was to form a 50-50 joint venture. But the night before the deal was to be signed in Paris in 2002, Bangur realised that it would be difficult to run a business by consensus. Also in time, as Vicat had more access to capital, it was likely that the Bangur family stake would get diluted. “If I could sell it this year, I was reasonably confident I could sell it the next,” he remembers. After a quick call to his father, he decided not to go ahead with the deal even though Vicat agreed to raise the offer.

Subsequently, Bangur got to work at turning around operations. Help came in the form of pet coke marketed by Reliance Industries (owner of Network 18, which publishes Forbes India), which was trying to promote it as an alternative to coal. While Reliance had approached several companies, Shree Cement was the first to try it out. Prashant remembers that pet coke was 30 percent of the price of coal and “that resulted in a huge cost advantage”, he says.

But in making the switch to pet coke, the company lost significant production. Workers had to be sent to Germany for training so that they could gain on-the-ground knowledge. Furnaces had to be modified and oxygen levels increased. The pet coke had to be ground finely so that there was a larger surface area to burn. Every 3-4 days, the furnace would stop working. But the lower energy costs were enough to make the plan worthwhile to pursue. Prashant estimates that in the first two years of using pet coke, they lost 30 percent of production, but as the market for cement had shrunk, the effective loss was only 5 percent, or 100,000 tonnes.

But Bangur made the bold call to persist with using pet coke. Fortunately for him, the market was just emerging from a downturn and he was able to use this time to effectively understand the new technology. “Whenever someone [people from other cement companies] would call us, we would tell them using pet coke is very difficult. But we still persisted,” he says.

(As an aside, Bangur mentions how they helped Nestle destroy its Maggi stockpiles after the company decided to withdraw them from the market in 2016: 6,800 tonnes were burnt in their furnaces for which Nestle paid them ₹4,250 per tonne.)

After the turnaround was complete, Shree Cement steadily expanded capacity. And even though it readies to breach the 40-million tonne mark in 2020, Bangur mentions that the company still has a long way to go. “If we say that we’d like to grow at 12 percent a year, then capacity should double every six years,” says Bangur. While this may sound fanciful, there is a real possibility that India may run out of limestone to support cement expansion in the next decade. At present, the limestone capacity is enough to support 600 million tonnes of production as against an installed capacity in the country of 400 million tonnes. As its production base has increased, the company has rationalised its brands. It now sells only the Bangur Cement and Shree Cement brands and has discontinued Rockstrong as the company believes it has properly segmented the market with these two brands. Both fall in the B-brand category, which means that they are not as expensive as an Ambuja Cement or Ultratech, but Bangur maintains that there is no difference in quality as they conform to ISI norms. All the work for both the brands is done separately. Even the sales teams sit in different spaces, the godowns are separate and the email IDs for staff have different suffixes.

One of the hallmarks of Shree Cement’s growth has been the fact that it has never diluted its equity base. It has done this by retaining profits that are then reinvested in the business; they raise debt where necessary. “Paying dividends after paying dividend distribution tax and then raising equity capital at 15 percent is self-defeating,” says Bangur. He prides himself in saying that the company is working first for the shareholders. Its per share cement production capacity has now ballooned to 800 kg per share.

Bangur, who till a few years ago would still take the Common Aptitude Test for IIMs every year to assess his skills, is nowhere close to done. His mind is sharp and agile. He’s not afraid to voice his views on the economy. He believes that the earlier growth was on a shallow base and could not be sustained. “We like individual good and collective pain. What we are going through now is individual pain and collective good,” he says, alluding to the fact that banks are being asked to rein in their bad loans.

As the avenues to expand in India get limited, Shree Cement has already started scouting for locations abroad, Bangur says. The company has looked at East Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. “We are looking at areas that are familiar with Indian culture,” he says. This is also being done so that the company can deploy its capital judiciously. Clearly, the company is on rock-solid ground, but it isn’t worried about finding its feet on newer terrain, under the aegis of its bold leader.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X