Election effects: Expecting the unexpected

The Sensex was up 4.6 percent in the three sessions since the results were declared, and the market had shrugged off the poll results

Image: Kunal Patil / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Image: Kunal Patil / Hindustan Times via Getty ImagesHow do markets react to unforeseen events? The state election results on December 11, which saw the BJP lose its majority in three states, were expected to result in declining stock markets. Instead, the opposite happened. The Sensex was up 4.6 percent in the three sessions since the results were declared, and the market had shrugged off the poll results.

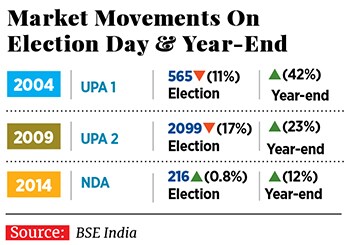

In doing so the Indian markets follow a global script: When Donald Trump won the US presidential race in 2016, the Dow recovered within days; when the UK voted to leave the EU, the FTSE began pricing in higher profits for British exporters due to a weaker pound. Similarly, in 2004, the NDA’s shock defeat had prompted a quick brutal correction before rising corporate earnings resulted in a four-year bull run. The 2009 UPA’s re-election euphoria was short-lived, despite the markets hitting two upper circuits on election day.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X