FMCG: Consumer stocks lose their shine

Indian consumer companies are no longer market darlings, although Nestlé and Hindustan Unilever stand out in a challenging environment

An extended period of lower growth could see a further decline in the valuations of FMCG companies

An extended period of lower growth could see a further decline in the valuations of FMCG companiesImage: Kuni Takahashi / Bloomberg via Getty Images

In the decade since 2010, buying stocks in Indian consumer goods companies had been a low-risk, high-return game. They grew revenues handsomely, generated predictable cash flows (which were mostly returned to shareholders) and had zero corporate governance issues.

One just had to invest in one or a basket of the dozen-or-so listed consumer businesses, hold them for a few years and count the gains. The Indian consumer with a per capita income of $3,000 (purchasing power parity) and rising was destined to continue to buy a little more of toothpastes, soaps and shampoos each year.

Analyst reports salivated at the prospect of higher incomes bringing in a hockey stock-like growth curve. In time, the per capita consumption levels would rival those of Thailand, Indonesia or Vietnam. There were new categories to introduce, new buyers to be brought into the fold and new business models to experiment with. All one had to do was discount the inevitable cash flows to their present value. What could go wrong? Plenty.

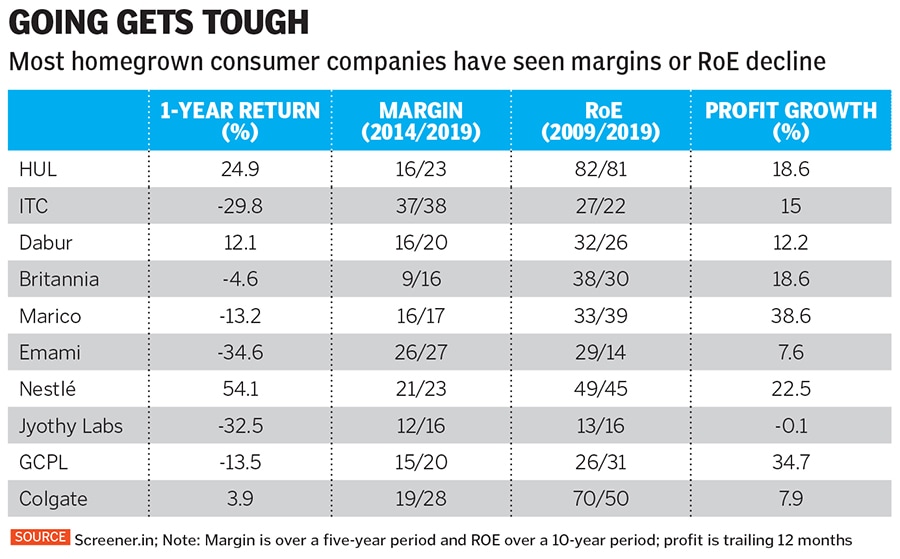

Starting 2015, when retail inflation fell and stayed on an average below 3 percent, consumer companies saw topline growth skid. An inflationary environment also meant that inventory adjustments would contribute to margins. Almost overnight, two critical levers of growth were lost. Add to that the lower margins that modern trade brings, a shift to cheaper low-unit packs and several companies found the going tough. Declining sales and lower margins, in turn, led to lower return on equity (RoE). Most homegrown consumer companies have seen either five-year margins or 10-year ROE decline. Investors voted with their feet and pulled money out from these expensive businesses. As the last year has shown, one can no longer buy just any consumer company and hope to make money.

The game, which till now had been played on rising topline, has shifted. “Over the last couple of years, FMCG companies have not been about topline growth but about margin expansion and profitability,” says Rahul Arora, CEO at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities. He argues that when the economy is slowing, companies cannot be expected to register strong topline numbers. As a result, volume growth, which has also been declining, is being seen as an important barometer of the health of these businesses. Those who just try and push sales will suffer an inevitable loss in profitability, he argues, as the era of secular growth, at least for the time being, is over.

In this shift, two companies—Hindustan Unilever (HUL) and Nestlé—stand out. Their roadmap to improved margins could provide a template for the rest of the industry as it looks to get out of a slump.

With its wide product portfolio, HUL has worked on premiumisation. What that means is that it starts with a small share of the consumer wallet and gradually grows that over the life cycle of that customer. A consumer who buys a ₹1 Sunsilk sachet is a potential ₹500 Lakme customer some day. Over the last decade, urban consumers have disproportionately shifted to higher margin premium products and HUL has the range to cater to their needs. It is a bit like Maruti that has worked on keeping car buyers hooked on to their brands, from Alto to Swift and the Ciaz. HUL has also controlled costs aggressively—everything from employee expenses to packaging costs. At its quarterly earnings press conferences, its chairman Sanjiv Mehta makes it a point to talk about their cost reduction targets. A wide product portfolio has ensured that HUL can bargain or demand better shelf space with retailers. There is also a constant push to repackage and relaunch products to generate excitement among consumers.

This has resulted in HUL’s margins expand every quarter for 34 quarters. Its outperformance in the last two years has meant that HUL, despite its larger size, has given investors higher 10-year returns (24.7 percent) than Marico (19.5 percent), Dabur (20.4 percent) or Godrej Consumer (22.4 percent)—the top three homegrown consumer companies.

Nestlé, which has a smaller portfolio, has also kept its margins intact (although its ROE dipped a bit in the last decade). Market share for Maggi is higher than it was post the product withdrawal in 2015 and the company continues to get favourable terms of trade from retailers.

An important factor for Nestlé and HUL scoring over their peers has been the consistency of their performance which is neither dependent on input costs (Marico, for instance, is overly dependent on the price of copra) or one product (Godrej Consumer Products is dependent on household insecticides, demand for which has collapsed). Colgate has seen its toothpaste portfolio challenged by Patanjali. When the Patanjali threat receded, Dabur, and not Colgate, gained market share with its ayurvedic toothpastes. At a time of slowing growth, these companies would do well to focus on profitability and holding on to market share.

At between 30 and 40 times earnings, even after the decline in the last year, Indian consumer stocks are not cheap. As blogger Rohit Chauhan explained, this is on account of the fact that the market believes there is still a probability of growth returning. He cites the example of Coca-Cola, which is a high quality, low-growth stock. Over the last decade, it has returned 7.18 percent a year plus dividends.

Even after the recent decline in margins and ROEs, Indian consumer companies are likely to remain high quality franchises. What remains to be seen is whether they return to their high growth path. An extended period of lower growth could see a further decline in valuations.

For now, “One can never rationalise the valuations of these companies for the growth they are posting,” says Raamdeo Agrawal, chairman of Motilal Oswal. Their recent troubles notwithstanding, he still has faith in these companies.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)