When the Milk Runs Dry: India's New Dairy Policy

From being proudly self sufficient, India now faces a dairy shortfall

Very few kids growing up in the 1980s and the 1990s in India are acquainted with the concept of a milk shortage. The main reason for this is the success of the four-decade-old Operation Flood, the dairy development programme started by India’s National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in 1970. One of the largest of its kind, the programme’s objective was to create a nationwide milk grid. It resulted in making India the largest producer of milk and milk products in 1998.

So, when NDDB chairman Amrita Patel painted a different picture while speaking at a national gathering of the dairy industry last month, it grabbed national headlines.

According to Patel, rising incomes have led to a shift away from cereals to vegetables, milk and meat. While milk production has so far been able to meet demand by growing at 3.5 million tonnes a year or 4 percent, it will now have to grow at 6 percent to keep up. Efforts to increase production have proved unsuccessful as the industry struggles with poor quality animal feeds, low yields and poorly bred cattle.

This was followed by a warning by the Economic Survey, a fortnight later, that unless production increased from 112 million tonnes to 180 million tonnes a year (an annual increase of 5.5 percent) in the next decade, India will need to import milk. The Survey also said that the recent spurt in milk prices does not bode well.

What ails the dairy industry and does India have a plan up its sleeve?

India’s dairy industry has chosen to follow a disaggregated production model. This means that large cattle farms using scientific milking techniques are few. Individual producers, who own a small herd and supply it to co-operatives, together with private dairies, account for 20 percent of the milk produced in India. The unorganised sector comprises the remaining 80 percent.

The co-operative model harks back to the days when capital was scarce and private enterprise frowned upon. “It has resulted in milk getting the highest price realisation among agri products, with 70 percent of the price paid by the consumer going to the original producer,” says R.G. Chandramogan, chairman and managing director of Hatsun Agro Product, the largest private dairy in India based in Chennai.

But at the same time, individual farmers inevitably lack the means to invest in improving cattle yields. Parithibhai Bhatol, chairman of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), which sells milk products under the Amul brand name, says he can only borrow money at 10-12 percent interest as against the 4 percent interest that is given to farmers. Many GCMMF members have held back their expansion plans because of the high cost of capital, says Parthibhai.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Fodder prices have risen from Rs. 4,500 per tonne to Rs. 7,000 per tonne in the past two years, creating another disincentive for producers to expand, according to N.R. Bhasin, president of the Indian Dairy Association. Exports of oilcakes, a key fodder input, crossed Rs. 10,000 crore last fiscal.

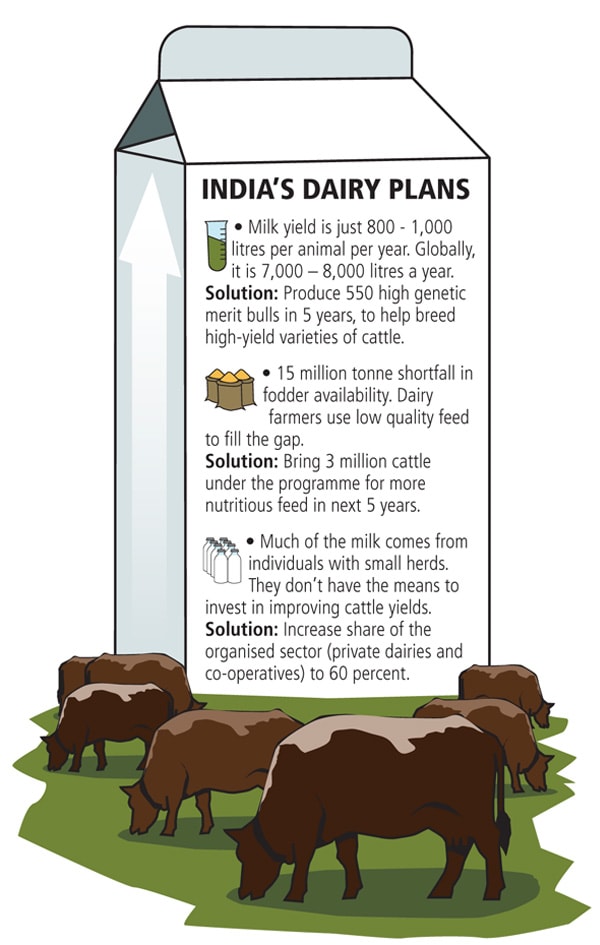

Patel estimates that while the demand for fodder is about 30 million tonnes, only about 15 millions tonnes are available. At times like these, many producers usually resort to feeding cattle leftover feed from their farms, which lowers yields further.

Productivity of Indian cattle is between 800 and 1,000 litres of milk per animal per year as compared to between 7,000 and 8,000 litres per year for the best varieties around the world, according to Pankaj Gupta, practice head, consumer and retail, Tata Strategic Management Group.

In the past two years, milk prices have risen by 13-15 percent a year to Rs. 28 to Rs. 30 a litre, with some states increasing prices every month. The government banned exports of milk and milk products this February in order to tide over the present shortfall; a move that was opposed by

the industry.

“We are not for or against an export ban. What we are against is an inconsistency in government policy,” says Devendra Shah, chairman of Parag Milk Foods, a Pune-based company. According to him, it hinders the industry’s ability to plan ahead.

For now, the government realises that increasing milk production will require its active support and has formulated a National Dairy Plan that aims to double production in the next 15 years. Rs. 1,584 crore has been earmarked for the first phase, which kicks off later this year once approvals are received.

Improving cattle varieties by breeding them through artificial insemination forms the cornerstone of the plan. In the next five years, these cattle breeding centres aim to produce 550 high genetic merit bulls a year. At present, 45 million farmers make use of artificial insemination. This will be expanded to 95 million in the next five years.

To shift production away from the unorganised sector that consists of farmers with a few cattle, the Plan aims at increasing the organised sector’s share to 60 percent, allowing for expanding processing facilities.

Lastly, it is the extension, education and delivery of services to the milk producers at their doorstep that will be the real challenge, said Patel, speaking at the convention. The National Dairy Plan is still working on addressing this.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)