Kishore Biyani is Back From the Brink

Kishore Biyani led the retail revolution in India but was also guilty of trying out too many things. A full-blown crisis later, he is ready with an equally grand but a more sedate growth plan

On what seemed like a regular Friday evening, Home Town was teeming with a few hundred excitable shoppers. A furnishings store in Vikhroli, a Mumbai suburb, it offers everything from iron nails that sell for a few rupees to shower enclosures and jacuzzis that cost over a lakh. The reason they were there was that each of them had succumbed to the oldest four letter word in history — S.A.L.E (well, the second oldest actually!).

Sofas could be had at 40 percent off their regular prices while Panasonic 42-inch flat-screen televisions were on sale at Rs. 38,000 apiece. And on Independence Day when the sale ended, revenues at the store touched Rs. 2.1 crore — the most money any store earned on a single day across the Future group’s network.

Sure, it’s the kind of number that gives credence to the boom in India’s consumption story and perhaps signals home furnishings may well be the next big thing. But it also signals the second coming of Kishore Biyani — India’s original new kid on the block and the architect of India’s largest retail network.

The funny thing is, when Biyani first invested in the 200,000 square feet property in early 2008, it wasn’t meant to be a home furnishings store. Like everybody else, he was caught up in the euphoria of sunrise businesses like retail and was trying to grab every little piece of real estate he could lay his hands on. The original plan was, politely put, vague. Something like open two separate stores from among the many formats his group operated.

Then Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008 and the world changed.

The crisis that followed blew a hole in Future group’s portfolio. Sales plunged; bankers who until then had queued up at his offices started to call in their loans; mutual funds that had invested in his companies buckled under redemption pressures and decided to get out; sources of foreign capital dried; his market capitalisation plunged two-thirds in a matter of six months; and Biyani who had invested way ahead of the cash flows from his network found himself trapped.

At Home Town, sales had plunged 30 percent. In any case, the format was still to demonstrate it could deliver profits. In a chat with Forbes India at his quirky office in Mumbai Central, Biyani admits he’s given to whimsical decisions. Nothing else, he said, could explain why he asked his team to convert the entire property into India’s biggest home furnishing store. They looked aghast, but complied.

Damned right he was. This year, the store is on track to bring in revenues in the region of Rs. 200 crore. Biyani claims Home Town has an order book of Rs. 1,000 crore because real estate developers have cottoned on to the idea of selling furnished homes. And new home buyers are looking for a one-stop shop. “The success of that one store energised the entire organisation,” says Biyani.

The fact is Biyani isn’t crawling out of the slowdown. He’s tearing out of it. By the end of this financial year, the group’s turnover is expected to cross Rs. 8,000 crore, up 27 percent from Rs. 6,342 crore the previous year. (This includes some double-counting because parts of the group buy and sell things to each other).

What makes these numbers remarkable is that even before the downturn struck, Biyani was being written off. In 2006, the Reliance juggernaut had announced its intention to get into retail with Rs. 25,000 crore to back its plans. The A.V. Birla group stepped up its plans as well to launch a chain of supermarkets and hypermarkets. Clearly, competition from deeper pockets was a big threat.

“Then, they said we didn’t have the capital to play this game. When the slowdown struck, they said we’d go under,” says Damodar Mall, Biyani’s trusted lieutenant, who now heads integrated food strategy for the Future group.

By all indications, Reliance Retail is still coming to grips with the nuances of the retail business. A.V. Birla, too, is trying to fix its retail model. Even as rivals regroup, Biyani is pushing full steam. While the slowdown exposed chinks in his armor, he kept his head down and fixed his problems with debt, focussed on cash flows and drove for greater efficiencies. “Most senior people were focussed on driving costs down,” he says. “They’d even switch off their air conditioners.”

Clearly, the gut-wrenching experiences have taught him a few lessons. The question is has he changed forever as an entrepreneur? Is it possible that when the dark clouds dissipate completely, the group will lapse back into its old, reckless ways? The answers perhaps lie in the way Biyani is bracing himself for the future.

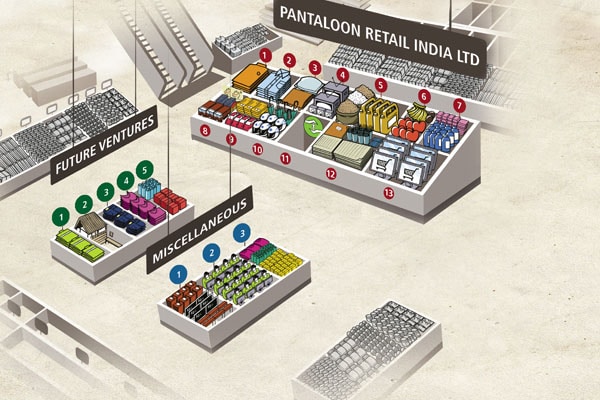

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

PANTALOON INDIA

1. Pantaloons Sells branded clothing. Strong on private labels like John Miller, Rangmanch and Urban Yoga.

2. Central High-end branded clothing; stocks labels from a host of brands like Benetton, Lee and Levis.

3. Home Town Furniture and furnishings. New business that should bring in 30 percent of turnover in 5 years.

4. Ezone Electronics. Loss-making business that the group plans to grow as they drive footfalls in stores.

5. Big Bazaar Provison and other household products. Format best suited for first time supermarket shoppers.

6. Food Bazaar Grocery. An extension of Big Bazaar format for food.

7. KB’s Fair Price Kishore Biyani’s answer to the kiranas. Small neighbourhood stores with limited availability of items.

8. Future Supply Chain Transports goods for the group and also sells its services to other parties.

9. Future Capital Holdings Loans and credit cards; plans to sell his stake in the business soon.

10. Future Generali India Insurance General insurance sold through kiosks set up mainly in Biyani’s stores.

11. Future Generali Life Insurance Life insurance — again sold through kiosks set up in Biyani’s stores.

12. Future Staples Stationery; world’s largest office supply chain store.

13. Future eCommerce ebusiness; platform to buy on the Internet anything from the Future group stable.

FUTURE VENTURES

1. Indus League Clothing Independent brand.

2. Aadhar Rural standalone stores bought from Godrej.

3. Lee Cooper Independent brand.

4. Celio Independent international brand.

5. Capital Foods Packaged foods.

MISCELLANEOUS

1. Future Human Development Soft skills training visual.

2. Future Knowledge Services IT networking and back-end services for the group.

3. Future Brands Private labels created by the group with the potential to go global.

The Perfect Storm

Actually, Biyani’s troubles began well before the financial meltdown starting towards the end of 2008. The listed entity, Pantaloons Retail had an overleveraged balance sheet with a debt to equity ratio of 3:1. Its rapid expansion had required short-term borrowings. Under Biyani’s messianic zeal, the group opened too many fronts — book retailing, electronics, sports, salons, apparel.

The Lehman bankruptcy put an end to easy credit and the business began to feel the pinch. With developers in bad shape, future expansion was put on a hold. “There were a couple of days when running scared, I could have taken any decision,” admits Biyani.

This was indeed a decisive moment for the man who started life on the fringes of the Indian retail industry in the mid Nineties. Till 2001, no one quite took notice of the inarticulate, fidgety man. The media shunned him, bankers couldn’t figure him out — and peers didn’t take him seriously. They simply couldn’t understand why Biyani kept harping on the need to think local, and fretting about borrowing retailing concepts from the West.

All that changed once Biyani discovered Big Bazaar, a quintessential desi format. In one year alone, the three stores of Big Bazaar did Rs. 200 crore of business. Money remained an issue though till Biyani decided to do the conventional stuff that most bankers looked for: Hire top notch talent, woo bankers and learn to communicate with media. Thereafter, there was no stopping him. Riding on the back of the Big Bazaar success, Biyani hit centre stage. Suddenly, media couldn’t have enough of him. He was on magazine covers, television shows on entrepreneurship; he was the star speaker at any retail forum and even went on to author a book.

In those heady days, it was easy to lose one’s head. Today, Biyani admits as much. “I think markets were behaving differently. Everybody was telling you that you’re smart. Every day, you looked in the mirror and you thought you were smart,” says Biyani.

After the downturn, he landed with a thud. In any case, 2009 was proving to be a tough year for Indian retailers. Slowing growth and job losses had resulted in lower footfalls. While the food and fashion businesses held up, customers baulked at buying items with higher sticker prices, many of which bring in better margins for retailers. The brisk expansion of the previous two years left retailers gasping for capital that had almost overnight become hard to find.

Most prudent retailers like Shopper’s Stop would look for outside funding only for the initial expansion; subsequent store openings are funded by internal cash flows. But Biyani chose to expand faster than his cash flows allowed, based primarily on borrowed money. The two years from 2006 were heady times for the industry. It seemed as if he was more focussed on valuations and growth and less on the cash flows and operating efficiency.

Now, faced with a severe crisis, the Biyani household began to do a fair bit of soul-searching. The man in the hot seat chose to act decisively. He used this chance to consolidate his balance sheet and get rid of loss making businesses. As many as 200 mid-level managers were asked to leave, a decision that Biyani says he now regrets. Anything to do with retail has been brought under the Pantaloon Retail umbrella with businesses like Future Brands and Future Realty hived off. At Future Capital Holdings, he’s recently brought in V. Vaidyanathan from the ICICI group to run the show and restart the operations which had floundered soon after launch.

Along the way, he also rolled over debt. Most of the debt will now mature in three to five years. B. Anand, group CFO, says he’ll have to pay a little more in interest outgo for that, but at least he won’t have to worry about it during the next three-year growth phase.

For now, Biyani will concentrate his efforts on four large formats — Pantaloons, Central, Big Bazaar and Food Bazaar. That’s down from the over 22 formats he had just two years ago. Food, fashion, home and general merchandise are his main growth drivers. He’s also pulled out of joint ventures he’d signed on for, like the one with the French lingerie retailer Etam.

The Value of Delegation

But the biggest decision was to step back from daily operations. While he’s still passionate about visiting his stores, the overall responsibility for the retail business has moved to cousin Rakesh Biyani. Insiders at the company say the two are as different as chalk and cheese. While Kishore Biyani relies on his intuition, Rakesh Biyani is a methodical, numbers-driven guy with the patience to drill down and see a task through.

An upshot of this has been the company getting its supply chain in order. During the boom, it focussed on opening new stores and expanding business in existing ones. This frenetic pace of expansion led to the supply chain creaking under pressure. Fill rates (industry parlance for optimum availability of merchandise on shelves) at stores hovered at less than 70 percent. For global retailers like Wal-Mart in the US, fill rates are closer to 90 percent. (Future now operates at 80 percent).

“Life had already become a problem due to hyper growth and lack of consolidation,” says Rakesh Biyani, who went about setting the house in order. He estimates that the growth took away the group’s attention from improving logistics for about a year. For the fashion business, the company had 18 warehouses across the country. The delivery was poor and tracking orders within the system, which came in one of 60 different box sizes, was a logistical nightmare. Differing taxation rules across states meant that each warehouse had to place a different purchase order, leading to accounting complications.

Rakesh and his team, in their effort to streamline operations, reduced the number of stock holding points to five and delivery hubs to four. Vendors would ship goods to one of the delivery hubs from where they would be routed through the system according to differing demand in different regions. Warehouses were upgraded at a cost of Rs. 150 crore at a time when cash was hard to come by. The order processing system for each store was streamlined using handheld devices, RFID (radio frequency identification) technology and warehouse management systems for tracking goods within the system. With the distribution system toned up, Rakesh Biyani is confident he’s laid the foundation for a scale-up operation.

The Food Bet

For a long time, Biyani wasn’t entirely ready for a line of business that accounts for 55 percent of the Indian retail pie: Food — more specifically, fresh fruits and vegetables. Biyani was concerned about margins. If the foods business had dominated his overall portfolio, the blended margins would have been severely dented. And yet, as Biyani figured later through a detailed study done by McKinsey & Co, the group wouldn’t be seen as a significant player in retail unless it had a large-enough footprint in the business because fresh fruits and vegetables brought traffic to his stores.

Until then, fresh fruits and vegetables were outsourced to another retailer, like ITC Choupal Fresh. If it needed to be a dominant player, the Future group had to chart its own destiny.

All along, for the fresh foods business, Biyani followed one assumption: He looked upon himself as a retailer. He ruled out any investments in building a cold chain and trying to erect a farm-to-fork supply chain that many others like Reliance had begun. He believed it didn’t pay to invest on elaborate infrastructure. He also didn’t believe the hypothesis that 40 percent of fresh foods in India are wasted. “If that’s the case, the wastage ought to be visible somewhere,” quips Biyani.

When Reliance started implementing its plans, Biyani chose to watch from the sidelines. As things turned out, the Reliance Fresh expansion met with a series of setbacks. The cost of setting up the cold chain and warehousing infrastructure was simply too high. And it would have a huge impact on the final retail prices. Reliance has now shut down several stores that have proven to be unviable. Much the same thing is true of A.V. Birla’s More.

As for Biyani, he is now looking to build a low-cost distribution and sourcing operation for fresh food. That entails building linkages with a set of farmers in areas like Nashik and encouraging them to follow good practices. So to reduce wastage and retain freshness, farmers are given information on when to harvest. For instance, if the store does higher volumes over the weekend, farmers are asked to time their harvest accordingly.

Instead of buying from third party consolidators, Biyani is now buying directly from farmers. That ensures he gets to keep higher margins — and get fresh produce into his stores. But there’s a cost involved with setting up consolidator units across the country. “We’ve got to figure out how to offer something special that allows you to charge a small premium,” says Damodar Mall.

Now, this is where the Future group’s sophisticated understanding of Indian consumers kicks in. Last year, it conducted a detailed set of home visits across the country to build a better understanding of food habits. The size of refrigerators at Indian homes has increased over the years, says Mall. Which means, most households are now willing to stock up on perishables like fruits, vegetables, milk and bread for as long as a week. A closer inspection of the refrigerator also revealed that it often contains left-over food and plenty of work-in-progress items like chopped vegetables, chutneys and pastes.

Armed with these insights, Food Bazaar has taken over the fruit and vegetable sections of its stores that had been franchised to third parties. It is working with farmers in Kashmir and Himachal to buy apples directly from them, which will then be polished and pasted with stickers that indicate where it originates from. Adding this sticker allows Food Bazaar to charge Rs. 5 more per kilogram, says Vivek Dhume, director for foods. Next on the agenda are citrus fruits. Display areas have been spruced up. “We plan to celebrate fruits within our stores,” says Mall.

The other big plank of the strategy is to localise the offering as much as possible so that it is tailored for each community. Mall and his team have done a detailed study of eight major communities in the country to understand their customs. And this is the crux of how it hopes to compete with global chains like Wal-Mart and Tesco.

Food still has wide regional variations. For instance, a Bengali living in Delhi still prefers to consume Govindbhog rice. But until five years ago, she wouldn’t pay a premium on it if it was available at the local store. Instead, she would travel to the Bengali-dominated Chittaranjan Park area where it could be had cheaper. But things change and now time is at a premium. Mall reckons that a new market is waiting to be tapped. Under the Ekta brand, Food Bazaar plans to sell over 70 such ethnic foods, often at twice the margin.

Last month, in Kalyaninagar store in Pune, Govindbhog rice outsold even the local varieties, a surprisingly quick validation of the company’s efforts. Still, Ekta is only a small part of the private label (or private brand as the company refers to it) strategy of the group.

The fashion side has well established brands like John Miller, Rangmanch and Urban Yoga and Biyani is keen to recreate this on the food side as well where margins for in house brands can be two and a half times higher than brands the company has little control over. Research by Interbrand shows 80 percent of buying decisions in the case of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) are made in the store. So if one gets the private label business model right, the upside can be huge.

Enter Tasty Treat, Clean Mate, Care Mate, Premium Harvest and Sach, all of which have grown above expectations contributing 20-25 percent to the top line. Tasty Treat soups illustrate the company’s understanding of the consumer and how it has managed to market its brand in a market where multinationals dominate.

Store research showed customers were shy to admit they consumed soup in mugs, and not bowls. When the figures were tallied, 82 percent said they drank soup in mugs. The marketing response was swift and precise. A mug was given away with every two packs of soup bought and sales skyrocketed. It’s now the second largest soup brand sold in Food Bazaar. “Our biggest advantage is that we do our research ourselves in our stores due to our direct interaction and engagement with customers and don’t rely on an outside agency,” says Devendra Chawla, business head of food and FMCG, private labels.

Sach toothpaste is another success story. Again the team relied only on customers visiting stores to craft their strategy. They asked consumers which youth icon they identified with. Sachin Tendulkar was the overwhelming favourite. Housewives said he was humble and rarely seen on page 3. He’s someone they would like their children to emulate. Tendulkar was roped in and Sach is now the second largest toothpaste in Biyani’s stores. For the time being though, Biyani says he has no ambition of being an FMCG player and will stick to selling these products in his stores.

The next big thrust is to set up a food park near Bangalore, where the Karnataka government has given it cheap land. Pantaloon Retail has invited manufacturers of soup, noodles, and a range of Indian food items to set up shop there. It will buy these products for its own store brands.

The Future

The focus on fewer formats has helped ensure there is greater attention to growing big brands in the group, particularly Big Bazaar, which now generates more than Rs. 5,000 crore in turnover.

Although they can’t quite understand the logic behind crowded aisles and the seemingly chaotic nature of the chain, even foreign retailers grudgingly reckon Biyani may have discovered a truly pan-Indian model. Ashni, Biyani’s daughter, who trained at a design school in New York, is now leading a project to figure how Big Bazaar stores ought to look like in 2015. Quick change could alienate customers while slow change will lead them to competition, says Ashni. “In the times to come we will continuously be in touch with India’s idea of modernity. Our entire design or features of stores is going to grapple with that main concern,” she promises.

A new Food Bazaar store at Malleswaram in Bangalore will be her model for a destination store. Here, papads will be made live and fresh nimbu paani served. In future, Food Bazaars could also see live counters that grind chutneys and cooking pastes for customers, similar to salad counters in Western supermarkets.

Vibha Paul Rishi, who headed marketing for Pepsico in India a decade ago, is now the new chief marketing officer for the group. Her task is to track evolving customer tastes. “To grow, we have to come up with an overarching customer strategy, not one that tracks just SEC A and B,” says Rishi. Her aim is to start collecting data on customer preferences and bring in organised systems to track them using loyalty programmes. The group will be investing in analytics to track all the data and use it for target marketing campaigns.

So while Big Bazaar stays focussed on serving its customers and gradually upgrading as the customer base matures, Biyani has his eyes peeled on the opportunity on a more premium offering a few notches higher than Big Bazaar. For the past year, Biyani has been busy trying to frame a joint venture with Carrefour for a chain of midmarket stores. The talks continue.

As consumption demand kicks in, the Future group has one big advantage: it has mapped out all the major catchments across most tier-one, tier-two and now tier-three towns. “It is easy for us to expand into these locations because we know what to stock and how to roll out quickly in these markets,” says Mall.

On his part, Biyani says he is careful not to get carried away by his own breakneck pace of growth. “This time the pace will be a lot more gradual,” he says. But the data he offers as support isn’t exactly measured. “By the end of 2012, our group will be Rs. 18,000 to Rs. 20,000 crore in revenues, with close to Rs. 1,500 to Rs. 2,000 crore in cash flows. Since my capital deployment is only Rs. 600-700 crore, there will be some cash for mergers and acquisitions as well,” says the flamboyant Biyani.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)