Why doesn't India promote its rich cricket history?

In a country where the sport is considered religion, cricket libraries are crying for attention, paid ground tours like the ones organised at Lord's in England are non-existent, and an immersive experience for spectators is yet to be conceptualised

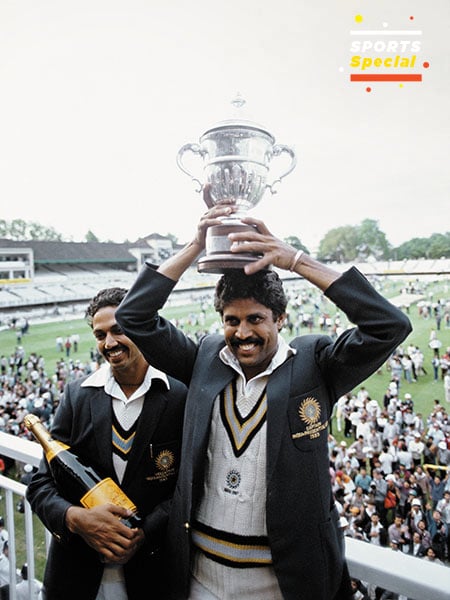

Kapil Dev (right) and Mohinder Amarnath after India’s historic win in the 1983 World Cup. The trophy was damaged in January 1999

Kapil Dev (right) and Mohinder Amarnath after India’s historic win in the 1983 World Cup. The trophy was damaged in January 1999Image: Adrian Murrell /Allsport /Getty Images

It took just 10 minutes of mayhem to damage one of the most coveted trophies of the country. In January 1999, members of a political outfit went on a rampage at the Board of Control for Cricket (BCCI) headquarters at the Cricket Club of India (CCI) in Mumbai to protest against the India-Pakistan bilateral series scheduled that year. The hockey sticks and stumps that they used to smash furniture and office equipment also left dents on the 1983 Prudential Cup. Several other trophies were broken too.

India’s unexpected win in that World Cup had nourished cricketing dreams for the likes of Sachin Tendulkar who would go on to become one of the greats of the game. From being the underdogs in 1983, India has now become a cricketing powerhouse with another World Cup win in 2011 and at the inaugural T20 World Cup in 2007. However, despite the game enjoying a religion-like status, the country has been slow off the mark in preserving its legacy, or, in some cases as above, gone ahead and ruined it.

Vandalism apart, cricket libraries are crying for attention, paid tours of grounds like the ones organised for visitors at Lord’s in England or Melbourne Cricket Ground in Australia are non-existent, and an immersive experience for spectators is yet to be conceptualised. “The problem is that cricket romantics are not in positions of power,” says Hemant Kenkre, cricket columnist and consultant with BVK Sports & Media, a Mumbai-based communications firm. “And I don’t think we have the intent to do that… you need someone passionate to drive such initiatives.”

Abhishek Dalmiya, joint secretary of the Cricket Association of Bengal (CAB), agrees. “What is most important are initiative and intention. If you have these two things, anything is possible,” he says.

The Melbourne Cricket Ground in Australia has guided tours for visitors

The Melbourne Cricket Ground in Australia has guided tours for visitorsImage: Scott Barbour / Getty Images

Among those who showed a genuine desire to do something in this regard was the late Raj Singh Dungarpur. The two-time BCCI president and former president of CCI wanted to build a cricket academy in Mumbai in the early 1990s on the lines of the Australian Cricket Academy as well as a cricket museum. He held a series of meetings with the likes of Sunil Gavaskar, the late Ajit Wadekar and the late Dilip Sardesai among others, in connection with it. Eventually, the country got a National Cricket Academy in Bengaluru in 2000, but the plan for a museum failed to materialise.

Other facilities continue to exist, but are either beyond the reach of the common man or in a shambles. Former India player Madhav Apte urged in good faith in 2014 to make CCI’s Anandji Dossa reference library available to the public. However, his request fell on deaf ears; only members of the club have access to it. A little over 2 km away from CCI, at the Wankhede Stadium, the Dr HD Kanga Memorial Library was in a sorry state even a year ago. A March 2018 report by Mumbai tabloid Mid Day said several books lay in a heap of dust and dirt in a corner near the lift of the media conference room. Ironically, the Mumbai Cricket Association (MCA) managing committee had approved ₹25 lakh for the restoration of old books in 2017 while a member decided to donate ₹5 lakh to recondition the tomes.

An MCA official tells Forbes India on condition of anonymity that the library has been shut for at least over six months. He claims renovation work is on, but has no idea when it would reopen. Apte says people don’t realise the importance of libraries and cricket literature, and the value they can provide to future generations. “We don’t see their worth,” he says. Kenkre believes the right people with zero political interest or no agenda should be given charge of such libraries, along with a free run. “Also, why can’t a reputed company or a conglomerate sponsor these libraries?” wonders the former CCI captain and member of the club.

The Lord’s Cricket Ground in England has guided tours for visitors

The Lord’s Cricket Ground in England has guided tours for visitorsImage: Shutterstock

The CCI, like Lord’s, has a glorious past, with the Brabourne Stadium having hosted its first Test match in 1948. Similarly, Kolkata’s Eden Gardens, which has a capacity of over a lakh people and has hosted the 1987 World Cup final, is regarded as one of the finest cricketing venues of the world. However, both these stadiums do not have tours for visitors. Neither does the Wankhede. At Lord’s, one can pay 25 pounds (₹2,200 approximately) for access to the dressing rooms, the pavilion, the hallowed Long Room and the Marylebone Cricket Club museum with a guide narrating anecdotes about the Home of Cricket.

The major difference between a place like England and India, says Apte, is people’s outlook. Because cricket originated in England and the first Test it played in 1877 was way before India did in 1932, they attach a lot of prestige to its heritage.

In India, on the other hand, pitches are targeted to make a political point. The Wankhede strip was dug up in 1991 to prevent Pakistan from playing in the city. And the Ferozeshah Kotla pitch in New Delhi was damaged in the hope that the India-Pakistan match at the venue in 1999 would get cancelled.

Dalmiya, who was also the former chairman of the New Area Development Commitee for the Northeast, concedes that “we have been able to do our master’s but the PhD is pending”. He believes that should such tours happen in future, people should not be charged for them. It should be a nominal amount at best for basic upkeep. “It’s a thin line, but one has to separate the business from the sport. At the end of the day, it is a sport. One cannot make it only a money-oriented thing. Balance needs to be maintained,” he says.

The Brabourne Stadium in Mumbai hosted its first Test match in 1948

The Brabourne Stadium in Mumbai hosted its first Test match in 1948Image: Ben Radford / Getty Images

The time, according to administrators and experts, is right to set the ball rolling, given that the 2023 World Cup is scheduled to be played in India. India’s growing clout in the cricketing universe and the success of the Indian Premier League (IPL) offer a chance to ensure spectators get their money’s worth. The eternal optimist that Kenkre is, he is hopeful that things will change for the better if like-minded people, including current and former cricketers, come together. Apte points to the need for the state to play its part to encourage these initiatives.

The Manchester United tour allows football lovers to sit in the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand and take in a stunning view of the ground, as well as visit the manager’s spot in the dugout. Dalmiya wants spectators to have a similar feel of the Eden Gardens: Enjoy a breathtaking view of the majestic ground while having a cup of tea. “Cricket is a passion that unites the country. The spectators are the biggest stakeholders… one must acknowledge their support and give them world-class facilities like a good cafeteria, museum, audio and video snippets with former players speaking about the game,” he says.

A portion of revenue generated from the IPL, says Dalmiya, should be reserved for these plans. “You have to give it back to people. You cannot sit idle and take benefit of the people who love the sport. The next couple of years are crucial, otherwise it will be difficult to catch up later.”

As a youngster, Sunil Gavaskar once famously asked his maternal uncle Madhav Mantri to give him one of his Team India caps. The former India player told his nephew that he should earn one if he wanted to wear it. Gavaskar not only did that but also became the first player to score 10,000 Test runs and held the record for the maximum number of Test centuries before Tendulkar surpassed his record. The incident, however, gives an idea about the fascination for cricketing memorabilia in the country and its untapped potential.

Rohan Pate, a former club cricketer who played for Maharashtra Under-19 and junior county cricket in Bristol, England, opened the Blades of Glory museum in Pune in 2012 because of his passion for the sport. He claims to have 31,000 items in his collection, including Donald Bradman’s bat and the pink ball used in the first day-night Test in 2015. The 5,000 sq ft facility also has rooms dedicated exclusively to Tendulkar and Indian captain Virat Kohli.

At least 450 international cricketers, from VVS Laxman and Kapil Dev to Wasim Akram and Chris Gayle, have visited the museum, apart from 16 lakh visitors. Pate, 31, feels the perception about museums being “old and boring” needs to change. He has, in fact, kept Tendulkar’s bat for people to hold and take photos with. According to him, these experiences make the visit worthwhile.

The way forward to preserving India’s cricketing culture is by changing attitudes. “Some officials are merely concerned about their state associations. Nobody looks at the country as a whole. Such a project requires a lot of hard work. You need someone to take an initiative,” says Pate. “It is important to preserve the game’s history because cricket has changed over the years. Future generations must get to know the change.”

It’s perhaps time to take fresh guard.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)