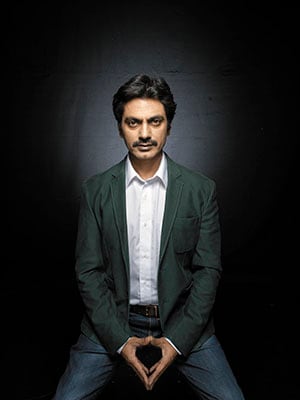

Nawazuddin Siddiqui: The drama king

The long struggle is over for the industry outsider. Nawazuddin Siddiqui, 41, is on every film-maker's most wanted list and, the actor says, he owes much of his success to his roots in theatre

The packed-to-capacity crowd at Eros theatre in South Mumbai erupts into animated applause the moment Nawazuddin Siddiqui arrives on screen. The actor, who essays the character of Pakistani journalist Chand Nawab in the movie showing there, Bajrangi Bhaijaan, is yet to utter a line, but that does little to mute the audience’s shrieks during a late-night show. Had Siddiqui been present in the cinema hall, this reaction would have warmed his heart. It was, after all, this chemistry between an actor and his audience that convinced him in the mid-1990s to pursue theatre and, along with it, a career in acting. And if his recent success and popularity are any indication, the connection has been well and truly made.

Today, Siddiqui, 41, is hot property in the Indian film industry. The three Khans—Salman, Shah Rukh and Aamir—count among his admirers and co-actors; a movie with the iconic Amitabh Bachchan is in the pipeline too. But this—the rubbing of shoulders with the leading lights of Bollywood and matching them dialogue for dialogue—is as unexpected as it is surreal for Siddiqui, who left his hometown, Budhana in Muzaffarnagar district, Uttar Pradesh, as a confused youngster in the early 1990s. “I was unsure about what I wanted to do. I was indecisive as boys at that age are,” he tells ForbesLife India. Yet, despite his slight frame, a physique devoid of ripped muscles and the looks of an everyman—physical attributes which are the exact opposite of those associated with the quintessential Bollywood hero—he’s carved a unique place for himself in the glamour industry and added his name to the wish list of several top directors.

It is tempting to call him unconventional, both on the basis of his appearance and unusual choice of roles, but he takes offence at the description. “People like me are branded unconventional, but I don’t agree with that. If you are using that word with reference to my looks, then it’s being racist,” Siddiqui says while his stylist blow-dries his hair and the make-up man conceals the slight hint of beard on his chin prior to a photo shoot for this magazine. “If people focussed on their looks in theatre, they would be termed as corrupt actors,” he points out.

He would know. The medium has played a pivotal role in shaping Siddiqui’s film career and destiny. And the deafening applause at Eros, and cinema halls across the country, is a nod to that leg of his journey.

Born to a farmer family in Uttar Pradesh, his parents wanted him to secure a stable job which would ensure a regular monthly income. One of nine siblings, Siddiqui completed his graduation in chemistry from the Gurukul Kangri University in Haridwar, following which he moved to Vadodara in Gujarat and worked as the chief chemist at a petrochemical factory for a year-and-a-half. The monotony, though, got to him and soon he was “bored of that job”. The only thrill in his life at the time was his occasional participation in Gujarati plays organised by the drama department at Vadodara’s MS University. (He pushed himself despite his lack of familiarity with the language.) The turning point was when he saw the play Thank You Mr. Glad. That experience sowed the seeds of the actor in him. “I was inspired by the amazing chemistry between the actors and the crowd after watching that show. And I decided to pursue theatre seriously.”

A friend suggested that he move to Delhi and study at the National School of Drama (NSD) since Vadodara only staged Gujarati plays. But it was easier said than done. Siddiqui failed to get admission. However, he did not leave the capital. Instead, he worked as a watchman in the city for nearly two years, earning a measly sum of Rs 600-700 a month to make ends meet. “I had to pay Rs 5,000 as deposit to get the job [of a watchman]. I mortgaged my mother’s gold jewellery in Uttar Pradesh to get that money, thinking that I’d repay the amount from my salary,” recalls Siddiqui. The financial hardships, however, did not deter him from pursuing what was slowly becoming an unquenchable passion—acting. He enrolled himself with an amateur theatre group in the capital, rehearsed for plays in the evenings and acted on stage in the mornings while diligently doing night shifts as a watchman.

Eventually, Siddiqui did crack the competitive NSD entrance exam and graduated from the institution in 1996. His stint there exposed him to a variety of Western drama and literature, and gave him a strong foundation in acting. “After joining NSD, I realised what one must not do in acting. That is also important. Till then, we thought changing one’s physicality or being loud was acting,” says Siddiqui. NSD, he adds, “taught everything lavishly”; it also opened a window to new worlds, for instance the Stanislavski school of method acting apart from opportunities to act in plays as diverse as Shakespearean comedies and those by Anton Chekhov. “Theatre explores all the traits of your personality. It has many forms and there’s experimentation involved. You become rich as an actor,” says Siddiqui. “Theatre belongs to an actor; films are a director’s medium.”

This explains why Bollywood as well as regional cinema in India have been blessed with several actors and directors who emerged from theatre: From Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri and Pankaj Kapur to Irrfan Khan and Manoj Bajpayee. It is impossible to leave Siddiqui out of that list today. In fact, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to suggest that his popularity rivals that of any ‘mainstream’ talent.

Had Siddiqui stuck to his original plan, Indian cinema would have been deprived of his talent. “I thought I’d do theatre all my life. I had no plans to come to Mumbai and act in films,” he says. After graduating from NSD, he had focussed on street plays and workshops in Delhi for five years because a trained actor like him was aware that the “process should not break”. “It is very important for an actor to stay busy and continuously hone his craft. I was working with the same intention,” he says.

The paucity of money in theatre is no secret. Even his deep involvement in plays could not make Siddiqui impervious to this bleak financial situation. “When you are young and have passion, you can do it [theatre] for years. As you grow up and realise that there will be more responsibilities, you know that this can’t go on,” he says. Some of his NSD seniors, like Manoj Bajpayee, had by then moved to Mumbai and gained some popularity by virtue of acting in Bandit Queen (1994), their first big project after graduation, and earning a handsome sum. Siddiqui thought it was only logical to try his luck in Mumbai and came to the city in 2000 “to act only in serials”. “After NSD, we had become ghamandi (arrogant) and thought we’d easily get work in Mumbai. But we soon realised that they did not need our kind of actors,” says Siddiqui.

A harsh reality stared him in the face; hardly anyone was willing to give him a chance. The skinny and inexperienced Siddiqui had to face rejection and contempt at every step. He claims he was bombarded with comments like, ‘Actor banney aaye ho? Lagtey toh nahi ho (You’ve come here to become an actor? You don’t look like one)’ at auditions. But Siddiqui quickly learnt to become friends with adversity. Work came in the form of crowd appearances in advertisements (he was a washerman in a soft drink commercial featuring Sachin Tendulkar), cameos in serials and small roles in C-grade movies like Joginder’s Bindiya Maange Bandook (2001). It was enough to keep him busy, but not something he wanted to flaunt. In fact, he says, he would hide his face, to avoid being recognised, whenever the camera focussed on him in the crowd. “My reputation was at stake. I wondered what my NSD colleagues would think of me.” Over the next decade, Siddiqui graduated to doing cameos in A-list movies such as Munna Bhai MBBS (2003), Ek Chalis Ki Last Local (2007), Black Friday (2007) and New York (2009). By this time, the actor had surrendered himself to fate. “After about five years in Mumbai, I convinced myself that I would get only these types of roles. I thought it is better not to have expectations, else it would result in disappointment,” he says.

But even though he underrated his own chances, there were others who noticed the spark in him, even in those blink-and-miss appearances. Director Dibakar Banerjee was one of them. “I wanted to cast Nawaz in a film since I saw him in Black Friday. He had a small role in the film, but he stood out. I was actually impressed when I saw him in Ek Chalis… and wanted him to play the character of Bangali in my film, Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! (2008). But I did not know his name then. I only knew him as the guy in Black Friday and was unable to figure out who he was,” says Banerjee, whose films Khosla Ka Ghosla (2006) and Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! have both won National Awards. The two went on to work together in Bombay Talkies (2013) in which Siddiqui plays a failed actor who struggles to make a living after his father’s death. “It’s my favourite, among all the roles I have enacted so far,” says Siddiqui.

Actor Manoj Bajpayee, who co-starred with Siddiqui in Gangs of Wasseypur–Part I (2012), echoes Banerjee’s views. “I always foresaw Nawaz becoming an actor of repute. I knew that the day he got a meaty role, he would succeed. That’s the best part about him… he was ready for the big thing,” says Bajpayee, who also played the lead in one of Siddiqui’s first plays, Uljhan, in which the latter was a tree and stood quiet for two hours with his arms stretched upwards.

A similar patience was needed in his seemingly-endless wait for substantial roles. It did not help that many of Siddiqui’s films struggled to find an audience here for want of promotion. In some cases, his films did not release in India despite winning acclaim at foreign festivals. (Dekh Indian Circus, for example, won the Audience Choice Award at the Busan International Film Festival in 2011.) However, cinema was seeing a definitive change at the turn of the millennium with directors willing to experiment. By 2010, the tide had turned completely and actors like Siddiqui were in demand, thanks to the author-backed roles written for them. And the meaty roles, that Bajpayee referred to, began falling in Siddiqui’s lap. The lineup: Kahaani (2012), Gangs of Wasseypur and Gangs of Wasseypur – Part 2 (both in 2012), Talaash (2012), The Lunchbox (2013), Badlapur (2015) and Manjhi—The Mountain Man (2015). In between, there was a smattering of commercial cinema—Kick (2014) and Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015)—and slightly offbeat movies like Miss Lovely (2014). “Thank god, there was a change in the way films were being made. There was experimentation and film-makers did not want a ‘face’ or a ‘star’, but an ‘actor’ to enact the roles. Else, it would have been very difficult for an actor like me. After Kahaani, Gangs… and Talaash, my life became simpler,” admits Siddiqui.

Not only has it become simpler, it has also become a movie script —a small-town aspirant with few ambitions, struggling to find his way as an actor, becomes a watchman by night and an amateur theatre performer by day. And all this even before his movie career began, which, it can be safely said, is segueing into a happy ending for our protagonist. Consider that in the space of a decade, the man who started with a one-scene role in Aamir Khan’s Sarfarosh (1999) was sharing significant screen space with the superstar in Talaash. While shooting for the film in Mumbai Central, Siddiqui gently reminded Aamir of his miniscule role then. This piece of information bemused Aamir who then brought the shoot to a halt and told everyone about the cameo. Aamir was one of the first people to see Talaash and he was so impressed with Siddiqui’s performance that he texted his co-actor at 2 am, saying, “You were wonderful… amazing.”

The appreciation and laurels began pouring in for Siddiqui from across the globe too, with his films making it to international festivals. At the Cannes Film Festival, six of his movies were screened in two years—Miss Lovely, Gangs of Wasseypur and Gangs of Wasseypur - Part 2 in 2012 and The Lunchbox, Bombay Talkies and Monsoon Shootout in 2013—a worthy achievement for any actor. It was a fulfilling journey for someone who would travel 45 kilometres from his home by bus to watch C-grade movies of Kanti Shah and Joginder in a theatre in Muzaffarnagar by paying Re 1 or Rs 2 for the ticket. For many people in the industry, though, it was still hard to place the ‘outsider’ as an ‘actor-hero’. When Siddiqui approached a fashion designer to style a suit for him for his appearance at Cannes, he flatly refused. “He probably did not believe that even my films could go to Cannes,” says the actor. Siddiqui then got a new suit stitched by a local tailor. The second time round, he says, a host of designers approached him, but he decided to wear an old suit instead.

Such experiences may have left him bitter, but they also helped the shy and reticent Siddiqui evolve as an actor. His leading lady in Manjhi—The Mountain Man, Radhika Apte, says: “The way he’s come up in life… that changes what work means to you after a point. Nawaz has seen sudden fame and adulation, but that has not changed his dedication to work. He takes his work very seriously. He does not like to take the limelight and wants to ensure that the entire thing works. People generally run after fame and money. Not him. His simplicity is his asset.”

Money, Siddiqui says, has never been a criterion for choosing roles. That explains him signing two movies in a day four years ago; one for Rs 1 lakh and another for Rs 1 crore. “The good thing about the industry is that you don’t need to quote your price. If you deserve it, you’ll get it,” he says, unwilling to name the two films.

What does he look for in a script then? “I only do stories which inspire me. I look for newness in the script, a character which I have not played before and doing something which will make me insecure. I want to break out of my comfort zone with each film. I don’t want to get trapped in one style. I wish to give something unexpected to my audiences; it is my responsibility to shock them with each film of mine,” he says.

At one point, Siddiqui was underrated and under-utilised. Not anymore. Now, directors are writing roles especially for him. “Nawaz is very special, the kind of actor who inspires material. I wrote the part of Shaikh in The Lunchbox with Nawaz in mind. I am always looking for an excuse to work with him and am writing something currently keeping him in mind,” says The Lunchbox director Ritesh Batra via email. Dibakar Banerjee describes him as “one of the finest actors in the world”. “His process is internal and hidden. It’s instinctive and deeply connected to the human details of everyday life. If I was a believer, I would have said it’s god-given,” he says. “Nawaz makes the character and the shot interesting even if he is not doing anything. He shares the trait with Irrfan Khan, Abhay Deol and Tabu.”

The ability to own and steal a scene despite being pitted against senior actors has been a result of intense preparation, something that he learnt from theatre. He would practise for plays for months and follows the same work ethic when it comes to films. For example, to play Dashrath Manjhi in Mountain Man, he went to the deceased labourer’s Gehlaur village in Bihar a week before shooting commenced. He interacted with the locals to understand Manjhi’s personality because he wanted to get all the characteristics right; after all, he had given his nod to play the character after hearing just one line. And for the scenes shot in Nashik jail for Badlapur, he regularly spent time with 20-25 inmates there to understand their mindset.

Such meticulousness rubs on to his fellow actors as well, who find an able ally to work with in Nawaz. Says Apte: “The best part about working with him is that he works together with his co-actors. A lot of actors don’t. So, there is collaboration. He is open to suggestions and accepts the right processes. There is no hierarchy. It therefore brings out the best from both actors.” Actress Richa Chadda had a similar experience with her Gangs of Wasseypur – Part 2 co-actor. “He’s a natural performer. He is very confident of his ability and that puts everyone at ease. It is always good to work with someone who motivates you to do better,” says Chadda, who is currently basking in the success of Masaan.

After spending over 15 years in the film industry, Siddiqui is still hungry to learn. “Acting is like a sea, the deeper you go, the more you discover things. My journey is still on,” says Siddiqui. “I am exploiting cinema and this wonderful phase completely. There’s no better time than now to be in films.” The challenge now, he says, is to choose the right roles. “Until there are complications and layers in a role, there’s no fun. If you want to be appreciated as an actor and be proud of your body of work, you must take risks.”

Siddiqui knows a thing about that too. He took a huge gamble in leaving his hometown and coming to Mumbai. And, despite the hurdles, it has paid off for him. He has quietly, and patiently, built a place for himself in a competitive industry and proved that, sometimes, even talent can be enough.

Today, he graces magazine covers, walks the red carpet at foreign festivals and is the toast of the industry. But this was never the endgame. “It was never my dream to become a star or a popular actor. I was happy with what I was doing, but did not expect this kind of success. Things just fell into place,” he says.

So he is learning to become comfortable with, and even enjoy, the spotlight. It is sensible he does that. Because the claps and whistles are only going to get louder.

Stage Pride Sonali Kulkarni, 40

Sonali Kulkarni, 40

The National Award-winning actress has been a staunch theatre actor who loved performing since she was a child. “Theatre began [for me] even before I could begin. I cannot differentiate myself from theatre,” says Sonali Kulkarni, who hails from the culturally rich city of Pune. Inspired and “deeply influenced” by her elder brother Sandeep—an actor and poet who also wrote plays—she began participating in local cultural programmes during festivals and training in classical dance. When she was in class XI, she participated in a workshop conducted by theatre guru Satyadev Dubey and realised “this is real freedom”. “I decided to become an actor then. Dubeyji played a huge part in moulding my personality,” says Kulkarni, who recently acted in Gardish Mein Taare, a play based on actor Guru Dutt and his wife Geeta’s life. Being an introvert, theatre, she says, provided her an outlet to portray the many emotions and observations that take place on a day-to-day basis. “Theatre involves expressions and that gives me a sense of lightness and fullness. You don’t feel empty because of the numerous characters that you essay,” she tells ForbesLife India. “Acting in plays is challenging because you don’t have close-ups. You can’t hide yourself… it’s not about styling.” The month-long preparation for plays helps in building the character as one can go down memory lane and refer to some inspiration or gesture, says Kulkarni, who has worked with the likes of Girish Karnad, Amol Palekar, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Farhan Akhtar and Gurinder Chadha in films. Having won accolades for her performances in regional cinema as well as Hindi films, Kulkarni says she is enjoying the process and earning well enough too. “I am getting appreciated too and that is what you die for. At the same time, you don’t want to be struggling for your rent,” she says, alluding to the lack of financial prospects in theatre.

(Image: Sunil Shirsekar)

She’s at the peak of her career with widespread appreciation for Badlapur, Hunterrr and the Bengali short film Ahalya, but Radhika Apte still has a special place for theatre in her life. “You do theatre exclusively for the love of performing. Theatre teaches you discipline, commitment, dedication, focus and the importance of practice. That is very crucial to keep your feet on the ground and for mastering your art,” says Apte, who recently acted in the Marathi play, Uney Purey Shahar Ek, directed by Mohit Takalkar. Like any youngster with an inclination for the arts, she took part in dramas in school. Later, at Pune’s Fergusson College, she was less in the classroom and more on stage. It was then while she was attending theatre veteran Satyadev Dubey’s workshop that Takalkar approached her to be a part of the play Brain Surgeon (2003) and his theatre group, Aasakta Kalamanch. Apte says she enjoys the process of rehearsing for months for plays even if it means waking up as early as 6 am for practice. The actress, who has signed a film with megastar Rajinikanth, finds the time to do theatre even today. “The film scene in Mumbai keeps you very busy because there are other things associated with it. As a result, you miss out on keeping in touch with your practice. That is the reason I need to go back to theatre,” she tells ForbesLife India. Though Apte says she would not like to be a part of the rat race, she wants to do a mix of films apart from plays. “For people like me who are not thorough [theatre] practitioners, we need something to support us because theatre does not pay. I am an actress who’d like to do everything. It’s not necessarily everyone’s ambition to become a top actress and make Rs 200 crore. And trust me, these big films are also very challenging.”

(This story appears in the Sept-Oct 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)