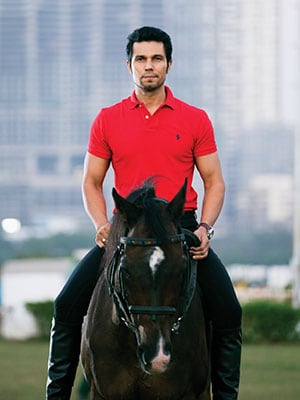

The real love of Randeep Hooda's life

Randeep Hooda is unapologetically the proverbial angry young man-both on- and off-screen. The actor, however, can also tone the intensity down a notch or two. Just watch him in the company of his horses

Randeep Hooda is furious, so much so that the angry red spots on his cheeks blend with the Ralph Lauren T-shirt he’s wearing. After spending 20-odd minutes lunging with his horse ‘Johnny Walker’ in a private enclosure at Mumbai’s Mahalaxmi Racecourse, the actor gives an earful to the caretaker for neglecting the animal’s upkeep.

The contrast in Hooda’s body language could not have been more stark: Barely 30 minutes prior to the outburst, the actor was beaming and cheering as Johnny Walker leapt into the air on his command. Realising the tension his sudden outburst had caused, Hooda, 38, later apologises to us during the short drive from a private enclosure to the clubhouse of the Royal Western India Turf Club (RWITC). “Sorry about that. It’s just that I haven’t been able to come here for a long time and these guys haven’t taken enough care [of the horses],” he says.

If he’s not shooting or busy with assignments, the actor commutes 25 kilometres one way every day from his residence in Yari Road, Andheri, to the racecourse to tend to his horses. He owns six of them, apart from the polo team, Royal Roosters, comprising 30 horses. “I find solace in my horses. I enjoy feeding them and being with them. Also, the racecourse is a vast expanse of lush green space. Where do you get such open spaces in Mumbai?” he says.

His time with the horses helps him escape into another world. A journey of self-exploration, far removed from the accolades he’s been receiving for his performance in Highway (2014) that reminded the industry of his potential.

And this journey inevitably takes him back to the mid-1990s, when Hooda, who hails from Rohtak in Haryana, moved to Australia because he was “feeling suffocated in India”. The turmoil within was becoming unbearable, he says, especially when he was a student at the Delhi Public School in RK Puram, Delhi—a city he describes as a “f***ing village”. “I grew up on Western music, movies and mindsets. I needed to get out of there [Delhi] and get exposed to the larger world. Of course, all those bikini-clad Aussie women in cricket stadiums were an incentive, too,” he smiles.

The script was perfect in his head, but life played out its own story. While pursuing his Masters in human resource management and marketing in Australia, he had to take up odd jobs to pay his bills—expenses for tuitions as well as nightouts. He worked in a Chinese restaurant, first as a delivery boy, then in the kitchen, and later as a waiter. His friend Francis would take him to guests and say, “Bollywood La, Dharmendra La”, while Hooda would stand next to him, avoiding eye contact. But it was a three-year stint as a cabbie in Melbourne that was an “eye-opener” for the small-town boy who aspired to be an actor. “It was my biggest education because people get into the cab and forget that you [cabbie] are there. You get to witness people in their elements,” says Hooda.

The little money he earned from these jobs paid for his “social life”, but Hooda wasn’t satisfied. “As a 21-year-old, you see people your age having a gala time and you are sitting in the cab waiting for the next passenger… all kinds of things cross your head,” he says. It also made him rebellious, he admits. Intensely so. He recalls how he did not complete his Masters and even “threw a book” at his thesis advisor. While he believed he had proved his theory on hedonism in 12 pages, his professor wasn’t willing to compromise on anything less than a hundred.

The transformation from a boy who was bullied in a hostel in India to a confident but angry youth was complete. “It [Australia] helped me grow as a person and as an actor. It also gave me an edge that a lot of people from small towns don’t have, of seeing a wider world and having a wider education. Usually, it is the prerogative of the elite to go to fancy universities. My education put me on par with these privileged people. And I realised that the fear I carried as a small-town boy was no longer there,” says Hooda, whose father is a doctor (now a professor) and mother, a social worker.

The physical and mental metamorphosis was visible by the time Hooda returned to India but, career-wise, he was still finding his feet. He took up a marketing job in Delhi just to prove to his father that he wasn’t wasting his time, but he did not turn up at the office because he thought he would never be able to do that kind of work. He felt disadvantaged in Delhi, which is entrenched in the “tu jaanta hai mera baap kaun hai? (Do you know who my father is?) culture”, and decided to move to Mumbai, “the only cosmopolitan city in India”. Soon enough (Hooda doesn’t recall the year), his friend, designer Varun Bahl, bought him a plane ticket to Mumbai, and thus began his pursuit of becoming an actor. In his early days in the new city, he slept on a friend’s couch, survived on boiled eggs, bananas and Aarey milk. “People buy you a drink, but nobody buys you food,” he says. A few modelling assignments kept him going, but the real struggle, says Hooda, was to find a place for himself in the film industry “I used to think I didn’t fit in there, at least then. Most of the movies made in the ’90s in India were crap. I am glad I missed that period. I often asked myself, ‘Kaunsi movie mein kaam karoonga, yaar? (Which movie can I act in?)’ I never aspired to work in the Mumbai film industry.” Rather, Hooda was hoping to work in a few Indian films, and put together a “showreel before heading West, to Hollywood or to Europe”.

The only person who he thought could exploit his potential was director Ram Gopal Varma; Satya (1998) and, later, Company (2002) were the kind of films he could picture himself in. But Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding (2001) came his way before he could work with Varma. After Nair called Hooda at his Delhi residence, he remembers going for the audition with his mother, and asking her to park the car two blocks away because he did not want anyone to know that he had travelled with her.

The small role in Monsoon Wedding led to more offers, but Hooda refused most of them. It didn’t help that by then Varma had promised to launch him in a big Bollywood production titled Ek, which never got made, and stopped him from working outside his banner. Varma paid him Rs 35,000 per month for three years. “I had no work. I was frustrated. I turned down many movies in good faith. But I complained to him [Varma] only once in three years. I really felt that he was the one man who could do something,” says the actor.

Varma eventually made D with him in 2005, but in the four-year period prior to that, Hooda honed his skills on stage by joining Naseeruddin Shah’s theatre troupe, Motley. “It [theatre] was very fulfilling. I had a student-like approach to life. I still do, and that’s what holds me in good stead,” he says. Surviving in an expensive city like Mumbai was tough. Hooda was paid just Rs 250 for a show at Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre, of which he spent Rs 150 on beer at a nice bar. “I ate in a dhaba-like place, but the beer had to be expensive,” he chuckles.

The high that he got from theatre translated into euphoria in 2005 when he saw his name on the big screen followed by the words “starring in and as D”. He says it gave him the false notion that all he needed to do was “stand in front of the camera and people will flock to see me”. He says, “I guess my small-town head came into the fray. I thought I was Marlon Brando with a Miss Universe as my girlfriend.” (Hooda was dating actor Sushmita Sen at that time.) His bubble burst soon after, when he found himself selling off his pressure cooker, TV and cars to pay the rent.

After a string of forgettable films, which made him an “unsuccessful actor”, Hooda bounced back with well etched-out roles and performances in Once Upon a Time in Mumbai (2010), Saheb Biwi Aur Gangster (2011), Jannat 2 (2012), Murder 3 (2013), Bombay Talkies (2013) and Kick (2014). “Just because I was in an Ajay Devgn movie [Once Upon a Time…] which was produced by Ekta Kapoor and directed by Milan Luthria, people said, ‘Isko acting aati hai (he knows how to act).’ It was then that I learnt that you need top banners and a big platform,” he says. “The kind of push and marketing a project requires and the opinion-makers’ good words it needs to get somewhere are things I realised after I worked in many great ideas.”

One such “idea” was Highway directed by Imtiaz Ali, whose hits include Jab We Met (2007) and Rockstar (2011). Ali decided to cast Hooda because of his “suitability” to the character of Mahabir Bhatti, a small-time criminal who abducts the daughter of a tycoon. “I had seen Randeep in a play and had always liked him as an actor,” Ali tells ForbesLife India in an email.

Playing Bhatti was a massive challenge, physically and mentally, for Hooda. “It was a f***ing depressing role. I hated it. Socio-economically, it was far lower than where I stand. Breaking that barrier is always hard. But it was a transformational role, something that I love [to do]. I had to attempt to be that person. Also, I got to see the country I belong to,” he says.

The language he spoke in Highway was not quite Haryanvi; it was Gujari, similar to the Hindi dialect, Brij Bhasha. He hired a tutor to get it right. The physical transformation was not easy either. To look the part, he exposed himself to the scorching sun for hours, did not bathe for days and eschewed moisturiser for six to seven months. “I wanted to look older, so I would keep scowling,” says Hooda, as he pulls a few faces for emphasis. The results were there for all to see. Or so he thought till Ali told him, “Sir, bohot achhe lag rahe ho [you’re looking very good]”. That remark petrified Hooda, who then drank an entire bottle of vodka and lay under the sun in Kashmir, where they were shooting at the time. Ali lauds Hooda’s thorough preparation for the roles he enacts. “He lives the life of the character while he is shooting, wears the same clothes and follows the same routine. For instance, even when he was not shooting for Highway, he used to drive a truck. That makes him a more believable actor,” he says.

Vishesh Bhatt, who directed Hooda in Murder 3, concurs. “You can make out from his choice of films that he is quirky and edgy. But he’s also a risk-taker and will stick his neck out if he’s interested in the subject. He’ll take up offers that the others would be scared of [accepting]. He has the guts, but is not reckless in his approach,” he says. Hooda’s honesty, says Bhatt, makes you realise that though he comes across as a hard nut from the outside, he is also vulnerable and courageous. Both these characteristics came to life as Bhatti in Highway.

Hooda’s earthy, rugged, rustic look in the movie did not stop female attention from coming his way. “That was never a problem,” he says. “People find me charming and appealing. That’s what I wanted to cut out [for Highway]. And lo and behold, they found me more appealing and charming,” he adds, laughing out loud. He, however, admits that though he previously didn’t care about how he looked during award functions, success has made him more conscious of his appearance. “I thought only what happened between action and cut was important. But that’s not the case. You’ve got to do b***s*** to be relevant,” he says.

He may well be wrong here. Because it is films like Highway that will ensure that Hooda remains relevant. The adulation is palpable but the actor insists that life hasn’t changed much. “It’s just that people are more sympathetic towards me. They say I didn’t get my due and that I am an underrated actor. But that’s still better than being overrated,” says Hooda, who is awaiting the release of Main Aur Charles, a biopic of serial killer Charles Sobhraj, made by Prawaal Raman.

According to Bhatt, one of Hooda’s greatest assets as an actor is that he seeks out the uniqueness of a filmmaker. This could explain the recent revival of the actor’s career. It is rare for an “outsider” to have a successful second innings in Bollywood, but Hooda has shown that it is possible. He says he goes purely by the roles offered to him, even if it means playing second fiddle to another star. “I’ve stood out in those roles,” he says. And he doesn’t care about the opinions of people. “Either you come and pay my bills or keep your opinion to yourself.”

The actor insists that he has finally reached a stage in life where he “doesn’t give a f***” about recognition as long as he is paid and gets to do the work he wants to do. “I live in my head. I blend into the environment, but don’t necessarily acquire it.” But for all his brash confidence, he feels that he has a lot more to give to his art. “I could do a lot better than I have so far,” says Hooda, who is also reticent about his personal life and relationships. Is love one of the things he craves, then? After all, by his own admission, he feels perennially lonely, but when he’s surrounded by people he realises “how irritating they are”. “I’ve learnt from experience that the only relationship you have to cherish is the one you have with your parents and your work. That does not mean I am averse to love and marriage. But I am not a normal person. I am not conventional. I don’t want to burden myself on someone else,” he says.

One relationship that hasn’t changed though is the one he shares with his horses. He kept them close to him even when he was struggling to make ends meet. “I did not sell my horses,” he says. And then, repeats himself: “I did not sell my horses.”

This love started in school but became an obsession about eight years ago. When Hooda saw Naseeruddin Shah wearing his riding boots, he told the veteran actor that he too loved horse-riding. “Naseer bhai asked me to take membership at the Riders’ Club [at the racecourse]. That was probably the biggest disservice he did to me,” says Hooda. He calls it a “disservice” because he is now addicted to his horses.

The actor looks at his horses as expensive, fragile sports equipment. “They are not my pets. I don’t put them in the living room. They eat and s*** a lot and weigh about 1,200 kilos each. Like you have soccer boots and a ball, in equestrian sports, your horse is your equipment. For me, it is a sport,” he asserts.

It is this conviction and love that prompted him to own a polo team, Royal Roosters, with Tarun Sirohi, ex-CEO of 61st Cavalry and former India polo captain, and friend Rohan Saharan, an Air India pilot. “Equestrian sports in India are suffering. Like kabaddi, polo is an Indian sport; it originated in Manipur. I decided to promote a sport that I play and spend so much time and money on. I want to turn it into a spectator sport. It is not a money-making venture for me,” he says.

On his own: “I live in my head. I blend into the environment, but don’t necessarily acquire it,” asserts the actor who calls himself “perennially lonely”

Hooda points out that it is a misconception that polo is a sport only for the rich. “You don’t have to own a horse to ride one. You can get membership (at the Mahalaxmi Racecourse) and pay Rs 100 a day (to ride a horse). Hiring cricket nets costs more and there is a queue for that,” he says. And there are several benefits associated with it. “It teaches empathy along with leadership. It keeps people close to nature,” says Hooda. “There are open spaces and great advantages for children to get involved in this sport. It develops your personality,” he says.

Horses aren’t his only interest though. He used to play the saxophone once, and is now waiting for a role that will rekindle his love for the musical instrument. As someone not fearful of communicating, writing is another activity that Hooda enjoys. But he adds that there is no question of maintaining a diary. “I can’t be regular with anything,” he says.

Often branded as brash and impetuous, Hooda agrees that his outspokenness has rubbed people the wrong way. “But nobody would say that I am not a nice guy or that I have swindled anyone. My conscience is clear,” he says.

For the greater part of the nearly three hours that ForbesLife India spent with him, Hooda regaled us with his wit, gave more than a glimpse of his eloquence and showed us why he is perceived as crazy and unpredictable. “There is no constant in life. I am not constant,” he admits, reminding us of his outburst earlier in the evening.

We say goodbye, and he flashes a smile that is at odds with his near-the-surface anger. He has to travel another 25 km to train for his new film, Do Lafzon Ki Kahani, in which he plays the role of a former mixed martial arts fighter. It will be another long and tiring ride back to Andheri. But for someone who journeyed to Australia and back in pursuit of a dream, he is unlikely to break into a sweat.

(This story appears in the Mar-Apr 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)