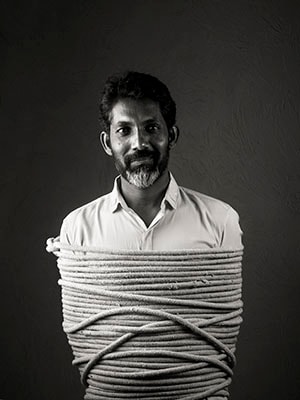

You don't need to have a grudge to depict society's harsh realities: 'Sairat' director Nagraj Manjule

Nagraj Manjule, whose Sairat has become the highest grossing Marathi movie of all time, talks about growing up as a Dalit in rural Maharashtra, and his anger against the establishment which goes beyond issues of caste

The first film by Nagraj Manjule, Pistulya (2010), a short, which he made while studying mass communication at the New Arts, Commerce and Science College in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, won him the National Award for Best First Non-Feature Film. The 38-year-old filmmaker’s next, the Marathi feature film Fandry (2014), received critical acclaim and the Indira Gandhi Award for Best Debut Film at the 61st National Awards. However, it’s his latest Sairat (which translates to wild)—the highest grossing Marathi film to date with Rs 68 crore in earnings as on May 20—that has elevated his stature as a master of his craft.

Sairat’s story, co-written by Manjule too, of two young lovers—Archie (Rinku Rajguru), the daughter of a landlord, and Parshya (Akash Thosar), a fisherman’s son—caught in the clutches of caste and economic class in rural Maharashtra has captured the imagination of not just the state, but also several parts of India and the globe.

Trade figures reveal that the film—produced by Zee Studios—is being screened in more than 500 theatres, including over 50 outside Maharashtra, with 14,000-plus shows.

It surpassed the record Rs 15-crore first-week collection of Natsamrat (2016) by earning Rs 25.25 crore at the box office; it eventually beat the Nana Patekar-starrer, which grossed a little more than Rs 40 crore overall, to enter the uncharted territory of Rs 50 crore for a Marathi film. Its commercial success is more evident when you consider the fact that ticket prices of Marathi films are a third of mainstream Bollywood films, and their distribution is largely regional.

Sairat’s dream run comes at a time when Marathi cinema is witnessing a revival. Court (2015), directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, was India’s official entry to the 2016 Oscars, while the likes of Lai Bhaari (2014), Fandry, Natsamrat and Killa (2015) garnered mass appreciation and commercial success.

In an interview to Forbes India, Manjule talks about his experience of growing up as the son of a Dalit labourer from Karmala in Maharashtra’s Solapur district, and the harsh realities of India’s caste system that shape his cinema (Fandry, too, is a love story that cuts across caste lines). Edited excerpts:

Q. Did you expect Sairat to be such a success?

I knew people would like it immensely, but I had no clue about how it would fare at the box office. When I narrated the script to my team, my friends and villagers, I got positive feedback. That gave me a lot of confidence. But after the phenomenal response to Sairat at its world premiere in Berlin in February 2016, it occurred to me that it could be a massive hit. The foreign audience loved the film and could relate to the story of youngsters in a remote part of Maharashtra. That assured me that people here would receive it well too.

Q. It’s one of those rare Marathi films where the story is told from the female actor’s point of view. Was it a conscious decision?

I am fed up of the male-dominated culture and the films that we have. I am tired of the usual portrayal of a good-looking, muscular hero saving the damsel in distress. Unlike Bollywood, where female actors are used just for song-and-dance sequences, I wanted to show a different side of a woman. I added colour to the girl I had imagined and, consciously or subconsciously, Archie became a strong, dominating character. While caste discrimination exists in our society, gender bias is an uncomfortable truth too. It’s worse for women because they are always treated as secondary human beings, irrespective of the caste they belong to.

Q. Why is caste so central to your films?

Because it forms a huge part of my personal experiences and is a social reality too.

Q. What were your experiences like?

While growing up, I did not know that I was bearing the brunt of being a Dalit. It is only now that I realise, what was happening was wrong. It was normal then, in the same way as it was normal for a woman to cook while the man sits in the living room. We were Dalits and considered tuchcha [inferior] compared to others. It’s so direct and so subtle that it does not lead to riots. Everyone knows their place in the village; there is a hierarchy that people are aware of. My horizons expanded when I began reading BR Ambedkar, Mahatma Phule and Chhatrapati Shivaji. I realised what our identity is and where we stand in society.

Q. Do you hold any grudges?

No. I don’t harbour any ill feelings. My anger and problem is with the establishment and the system.

Q. Do you portray that through your cinema?

It happens unknowingly. Only if you want to avoid the caste interplay in society do you need to try very hard. Otherwise, it happens naturally because that’s the reality. You don’t need to have a grudge to depict the harsh realities of our society.

Q. Are you trying to be the voice of the oppressed?

Perhaps [laughs]. I try to showcase reality through my films. Art is a mirror of society. I am not biased or angry despite what I have gone through. But I want to tell what’s happening in society, which is usually not shown in films.

Q. Sairat is also a love story. What’s your idea of love?

What new thing can you say about love? When you love someone, you shouldn’t look at the [other person’s] caste or economic status. But now we do. We exaggerate too much about love, saying it is blind and all. But, practically, you don’t see this kind of love in real life. Everyone does what’s right for them and then they call it love. I find that funny.

Q. Unlike Fandry, Sairat is touted as a commercial, mainstream film. Was it deliberate?

I don’t understand what’s commercial. Fandry, which was made on a budget of around Rs 1.5 crore, also did well, earning Rs 6-7 crore. Sairat’s story has romance, humour and fun. So it had to be shot that way, with songs and all. As a result, it became mainstream. I would never make a masala film just to ensure that it becomes successful financially. I’ll stick to the films that I want to make; if in the process they become commercial hits, I’ll be happy. I don’t bracket films as mainstream and art house. Sairat was screened in Berlin, so it’s also an art house movie; plus it’s a box office hit, so it’s a commercial film too.

Q. One criticism is that Sairat’s running time of three hours is too lengthy. Did you think of shortening its duration?

I did not think of trimming it even once. At the most, I would edit it by 5 minutes; I cannot cut it by 15 to 20 minutes. Length is not a physical thing, it’s psychological as well.

Q. The pre- and post-interval parts feel like two different films.

I don’t even consider an interval while making a movie. If you look at the film in totality, the story flows seamlessly. The interval is a very Indian concept.

Q. What’s with you and shocking endings that stay with the viewer?

The story has to end in some way. I do it my way. I cannot say what the impact is, but I like the way I do it. There is a plan, but it’s not to shock the audience.

Q. What does cinema mean to you?

I don’t think I can define cinema. I was crazy about films while growing up as they transported me into another world. I had seen Deewar, Khuddar and Coolie and I used to think of myself as Amitabh Bachchan. I would walk around with a knot on my shirt like the superstar did in his films. I wasn’t even aware of reality. Now, I am trying to bring reality into my films. I was in the audience once; now I am on the other side.

Q. What are your views on the changing face of Marathi cinema?

I love Marathi films, more than Bollywood. Content-wise they are superior and there is a lot of experimentation. The flavour can be seen in the kind of different stories that are being told. I feel blessed that I am working during such a wonderful phase where a lot of talented directors are making great films.

Q. The state has made it mandatory for theatres to reserve a prime slot for Marathi films. Your views?

I don’t think there’s fun in that. You can reserve a slot, but people don’t flock to the theatres just because a film has released. People came to watch Timepass, Duniyadari, Natrang, Natsamrat and Lai Bhaari because they were good films.

Q. With successes like Fandry and Sairat, you are being hailed as a game changer.

How can I say who I am? I am just doing my work. A lot more people know me now. But I haven’t changed. Of course, we become smarter and work harder. But as a person, you remain the same.

Q. What next?

I have some stories in mind, but I haven’t decided which to make into a film. I want to take a break for some time. I am not bound by any limits. If I feel like it, I’ll even make a Bollywood film. There is a future, but I don’t know if it’s bright or not [laughs].

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)