The theatre of sports

Bollywood has caught on to sports biopics as filmmakers depict real lives and humanise heroes

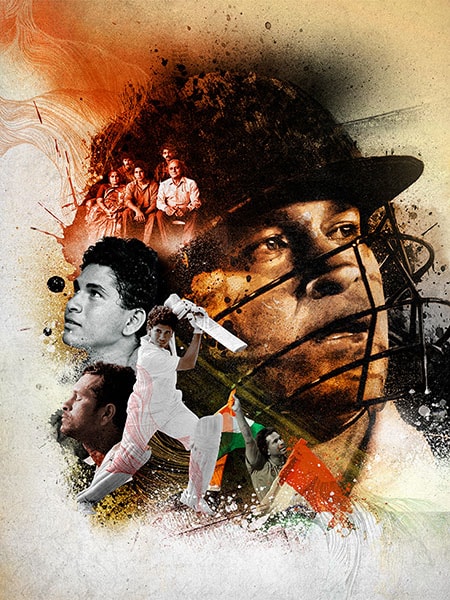

Sachin: A Billion Dreams is the latest in a growing list of films on the lives of sports personalities

When filmmaker Omung Kumar, then an art director of Chameli (2004), Black (2005) and Saawariya (2007) among others, wanted to start directing, his writer Saiwyn Quadras asked him if he knew the life story of boxing star and Olympic bronze medallist Mary Kom. Kumar didn’t, and Quadras insisted that he read about her. Hers was a compelling life story with a women-centric theme, he said.

Once Kumar learnt about the exploits of the five-time world champion, he flew to Imphal, Kom’s hometown in Manipur. At that point, he did not have a producer on board and “wasn’t sure if she’d be interested”. “But we clicked instantly. Within half an hour of meeting us in a restaurant, she gave her consent,” says Kumar, who made his directorial debut with Mary Kom in 2014.

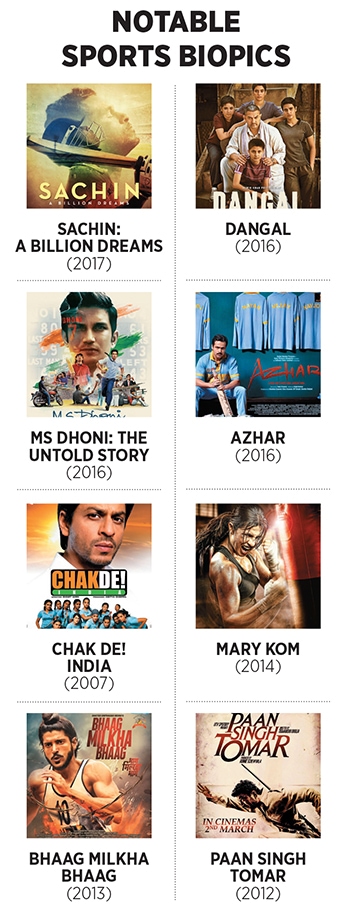

This was one in a series of sports biopics that has caught on in Bollywood, a trend kickstarted by Chak De! India, the story of former hockey player and coach Ranjan Negi, in 2007. Both Mary Kom and Chak De! India earned over Rs100 crore worldwide. Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), which depicts the life of celebrated Olympic sprinter Milkha Singh, raked in Rs120 crore at the Indian box office and over Rs250 crore globally, as did MS Dhoni: The Untold Story (2016), a narrative on the meteoric rise of India’s wicketkeeper-batsman-captain, earning more than Rs200 crore. The recently-released Sachin: A Billion Dreams, a docu-drama on the country’s cricketing god, has also had a fair run at the box office, earning an impressive Rs28 crore in its first weekend.

Bollywood has a strong line-up in the next few years as well, with biopics being announced on Saina Nehwal and PV Sindhu, India’s only two shuttlers with Olympic medals. Besides, director Aishwarya R Dhanush has announced a film on 21-year-old Paralympic gold medallist Mariyappan Thangavelu, while films are being planned on hockey legend Dhyan Chand and former All-England champion P Gopichand, among others.

For an industry that is obsessed with high-octane drama and song-and-dance sequences, what explains this glut of sports biopics? For one, India’s deeply-entrenched culture of venerating sporting glories. But these films perhaps owe their success in equal measure to the fascinating storytelling that humanises idols and brings out vignettes of their life beyond the sporting arena. Take Sachin… for instance. Tendulkar’s heroic feats over a 24-year career are well known. But as he himself has said, the film reveals the person behind the cricketer, his highs and lows, with rare real life footage from his personal and professional lives. For instance, moments with friends and family, celebrating daughter Sara’s birthday and training with son Arjun in England. It is this humanness that filmmakers look to tap into when they depict a sportsperson’s journey.

Similar sentiments were at play when Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra decided to portray the life of Milkha Singh. Having grown up in Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar, hearing poignant stories of Partition, Mehra identified with Singh, who witnessed the massacre of his family in the violence. The journey of a boy who did not have two square meals a day or shoes to wear, but went on to become an international athlete stayed with Mehra during his growing up years. Later, his interest was rekindled on reading the Flying Sikh’s autobiography, The Race of My Life. He sought a meeting with Singh and the more they spoke, the greater was Mehra’s conviction about making the film. “It was such a beautiful story… deep down in my heart, I was convinced that it needs to be told,” says Mehra. “It’s a human story, and also that of a brother and a sister. A story of a true Indian hero that is so entrenched in modern history.”

If the happy ending to the Dhoni story drew audiences to the cinema, the poignancy of the life of Paan Singh Tomar, the armyman and seven-time National Games gold medallist (in the 1950s and ’60s) who became a dacoit, struck a chord with the audience. In Mary Kom, too, director Kumar not only focussed on her triumphs in the ring, but also her fights off it. “There was a human aspect to her story,” says Kumar.

Making a biopic, however, is not easy. It not only requires immense research before it goes on the floors, but also makes actors walk the extra mile. Before Dangal (2016) turned out to be Bollywood’s top grosser with collections of over Rs1,700 crore worldwide (as of June 1), lead actor Aamir Khan, who played former wrestler and Olympic coach Mahavir Singh Phogat, had to pile on 27 kg, going from 70 kg to 97 kg, and then lose it.

Sushant Singh Rajput, who essayed the role of Dhoni in the 2016 film, underwent rigorous training to walk, talk and bat like the cricketer. He also watched several of Dhoni’s video interviews every day for hours for 10 months.

“I did not even know when I started walking and talking like him,” says Rajput. He also practised under former India wicketkeeper Kiran More to ensure that his physical and mental transformations were in tune with each other. “I put on weight and grew my hair… for 11 months, every 3-4 weeks, I would stay with Dhoni’s friends in Ranchi and tell them to talk to me the way they would with him,” says Rajput. One can expect a similar level of meticulousness from the actor on a film on swimmer Murlikant Petkar, India’s first Paralympics gold medallist, the rights to which he has recently acquired.

Directors lead from the front when it comes to doing their homework. Amole Gupte, who has announced a film on Saina Nehwal, has watched all the matches of the former World No 1 and has met key characters in her life, including her former coach P Gopichand, to understand the person behind the star. “The film will also be about her human side… not only badminton. You need all the colours to complete the painting,” he says.

One prerequisite for making biopics, according to filmmakers, is to be honest about that individual. There can be interpretations, but you can’t goof up. “You have to be true to the person. A biopic demands that. You have to be real,” says Kumar. Gupte concurs: “With my other movies, I was always trying to seek the truth. In this case, I am narrating her story. I don’t have to create it; just be truthful.”

Actor Sonu Sood, who’s gearing up to make a biopic on 2016 Olympics silver medallist PV Sindhu, says her family has made notes on the smallest incidents in her life to help the filmmaking process. Similarly, Mehra considers himself fortunate that he could get first-hand insights from Singh about the incidents that shaped his journey. “I was so lucky to get anecdotes from him and understand his conflicts. It enhanced my storytelling,” he says.

Shuttler Saina Nehwal on whom a film is being made

Image: Kumar/ Jass4team For Forbes India

Biopics have been made at different stages of a sportsperson’s life, some while they are still playing, and others after their retirement. Is there a right time to tell these stories? Is it too early to make a film on, say, someone like Nehwal and Sindhu who are still at the peak of their careers? Both Gupte and Sood disagree.

Nehwal, says Gupte, has already achieved iconic status and has brought a new wave in badminton. Her greatest contribution, he believes, is not just in bringing down the “Chinese wall”, but in getting children to play the sport across India. “The earlier you tell her story, the better. She is only going to rise further. This film is celebrating that,” he says.

Sood was among the millions glued to their TV screens when Sindhu fought and lost the Olympic gold medal to Spaniard Carolina Marin last August. “When she won the silver, every Indian felt like a winner,” he says. That’s when he went through her story and decided to make a biopic on her. “It’s tough to make a biopic while a player is playing. However, it’s not just about the rise and downfall of an athlete and when they retire... why not create something that’s already there and is making our country proud?” he says.

Given the emergence of new heroes from different sports, it is not surprising that their stories are finding resonance with filmmakers. Paralympic high jumper and 2017 Forbes India 30 under 30 alumnus Mariyappan Thangavelu says he is excited that a movie is being made on his life, taking his story to the world.

Mehra says the success of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag has proved that the audience is hungry for good content. “It was a pioneering effort and fortunately for all of us, the film did extremely well. That must have opened the eyes for all of us… there are so many Indian stories to be told to the world,” he says. Kumar, though, believes it’s just another genre that is being tapped by the industry. He says such films will continue to be made, as will movies on war and history.

However, the buzz around sports biopics should now make it easier for aspiring filmmakers to get funds for such movies. Mehra hopes that directors will no longer have to run around to justify the movie, like he did before making Bhaag Milkha Bhaag. “To pitch it to people so that they can buy into your dream was an uphill task,” he says.

In the same breath, however, Mehra says that when you attempt something, the idea should be to create a perpetual kind of an asset which gets more precious over time. “If the reason for telling a story is only to make money, somewhere the story will suffer. When you make such an attempt, you should give yourself the permission to fail,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X