Commercial real estate: A possible resurgence

A looming supply shortage, rising rental yields and capital values are driving investments in commercial properties

“We’ve reached a point where we believe that this is the right time to get into commercial property transactions,” says Jayesh Dattani, who manages the real estate investment desk at the family office of Narotam Sekhsaria, the erstwhile promoter of Ambuja Cement. His argument is simple: Unlike residential projects, commercial property offers investors the opportunity to make a respectable nine percent-plus rental yield. Add to that the scope of a decent price appreciation in select upcoming pockets in metropolitan cities across India, and investors find that risk/reward, at this juncture, favours the commercial real estate market. “The family office is actively looking at opportunities in pre-lease commercial space,” says Dattani.

While residential real estate faces a sustained and prolonged demand slump, commercial properties offer a glimmer of hope. The demand is coming from two sources: Patient high net worth investors (HNIs) and realty funds that hitherto had chosen to deal with only residential properties.

A significant example of this is global private equity firm Blackstone Group, which has over the last decade invested $3 billion into commercial real estate in India. Its marquee properties include Express Towers at Nariman Point in Mumbai. It also invested in a clutch of office space in Bangalore, which it owns in partnership with property development company Embassy Group. Other investors, who, for the most part, took their eyes off commercial assets in the last decade, are now starting to show interest too. A case in point is the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which recently tied up with the Shapoorji Pallonji Group to jointly purchase commercial assets in India.

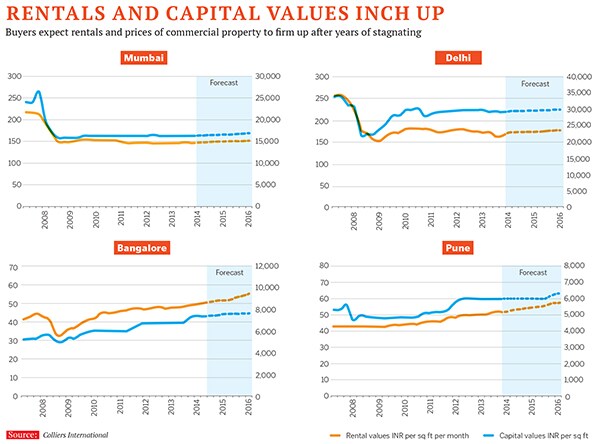

It is early days yet, but brokers are already seeing an increase in inquiries. “I have investors who are looking to buy commercial assets,” says Joe Verghese, managing director, India, at Colliers International, a real estate consultancy. According to him, this increased activity has come after a hiatus of about five years, one that saw both stagnant rentals (due to an oversupply in office space) and flat capital values (also the result of oversupply). But with renewed demand, both rentals and capital values, or asset prices, are now showing signs of moving up. This has led to a rise in investor interest. In 2013, companies rented 30.44 million sq ft of office space across India, according to Colliers International. The following year, that number rose by 17 percent to 35.62 million sq ft.

To understand why commercial properties are finding favour with investors, one needs to go back to the period between 2003 and 2008. Real estate across India was on steroids, and residential and commercial developers saw their capital values appreciate. In 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers caused a credit crunch, and prices of both types of properties took a tumble. Residential prices started climbing very quickly from 2009 onwards, but commercial real estate fared a lot worse. The prices of commercial assets in many business districts have only now managed to touch 2008 levels. But this relatively low capital value has resulted in higher rental yields for owners of these commercial assets. In the current market, residential assets—which have doubled and even trebled from the 2008 lows—fetch a rental yield between 1.5 to 2.5 percent. Commercial assets command anywhere between 8 and 10 percent.

Investors are also banking on capital values moving up. It helps that with the Modi government making all the right noises, there is a general uptick in business activity. “There is also the expectation that these assets can be spun off into real estate investment trusts (Reits), which is driving demand,” says Ambar Maheshwari, CEO of Indiabulls Realty Fund. (Reits are investment vehicles that have office spaces as assets and are traded like shares on the stock exchange.)

One concern for realty funds is the lack of quality commercial projects or Grade-A office space in industrial parlance. Real estate companies like DLF, which have a large portfolio of leased assets, have made it clear that they are not for sale. “After the top 10 or 15 commercial developments in any city, there is a sharp drop in quality and this is something savvy investors are not willing to put up with,” says a real estate portfolio manager. As a result, when a Grade-A property comes up for sale, there are often a dozen investors vying for it.

HNIs can afford to go down the quality chain and buy either floors or office zones in commercial developments. Investors usually prefer to buy such developments in districts that are likely to emerge as business hubs in 5-10 years. For instance, in Mumbai, areas like the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC), Goregaon and Thane are prime candidates. In BKC, Complex Capitol, a marquee development, was sold to investors on a strata title (piecemeal) basis. It is in this space that brokers have seen a noticeable increase in inquiries.

There is, however, no circumventing the lack of Grade-A properties. And all evidence indicates the fact that developers may not find it worth their while to make new offices, which in turn, will lead to a shortage in the market. There is a reason for this reluctance on the part of builders: They’ve been badly stung by the lack of demand in the last three years, and have stopped bringing in significant supply to the market. “I see the demand-supply equation changing in favour of buyers [who come in and buy now],” says Rahul Rai, head of ICICI Prudential Asset Management Company’s realty funds. Another factor that comes into play is that commercial real estate developers only start to recover their investments once the property is leased out. (Residential is self-financing as builders raise money from buyers in tranches.)

Pirojsha Godrej, managing director of Godrej Properties, says the entire debt load on his balance sheet is due to the commercial projects they are working on. “I would prefer to take on more residential projects in the future,” he says.

Investors, however, are happy with this delicate status quo: All signs point to commercial properties being a better bet than residential projects.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)