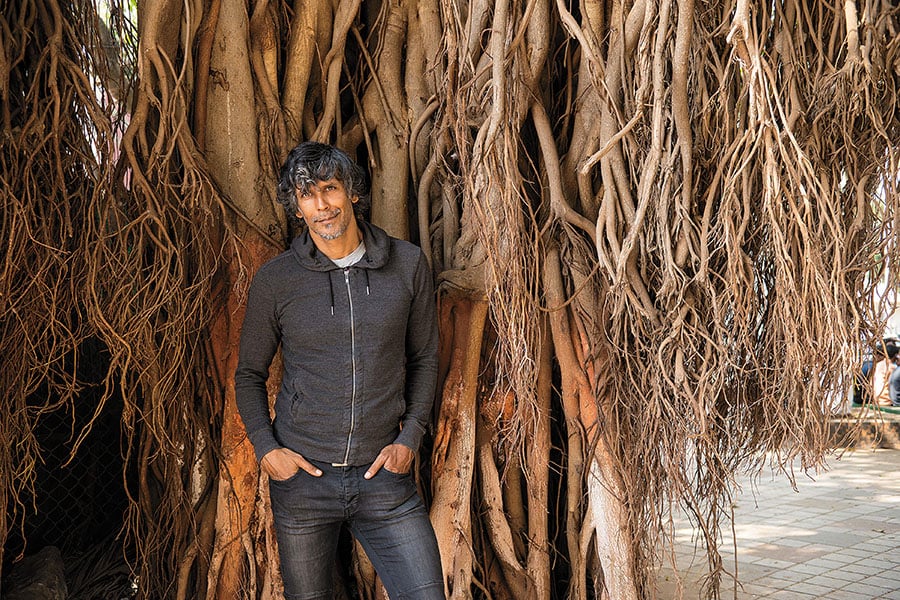

Milind Soman's life outside the box

With his autobiography out, Milind Soman, a man of many parts, talks about how his non-standard, multi-faceted life is really not worth writing home

Image: Aniruddha Chowdhury / Mint Via Getty Images

Image: Aniruddha Chowdhury / Mint Via Getty Images

After one of his training sessions at the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Swimming Pool in Dadar, Mumbai, Milind Soman—then a schoolboy—found a snake slithering on the road. Almost instinctively, he put it in his boots and took the reptile home. For the England-born Soman, who moved to Mumbai in 1973 at the age of eight, the company of animals was more comforting than interactions with people. “He was a loner and an extremely shy boy,” says his mother Usha, adding that her son had got cats, dogs, rabbits and turtles at their Shivaji Park residence.

His posh English and inability to fluently speak his mother tongue Marathi made Soman an outsider. “I was a misfit because I was a minority. I did a lot things that nobody else was doing. I didn’t know other people like me. And I never tried to fit in or have friends. I saw myself as being different because my interests were different. I had a lot of animals at home… I used to read a lot, and was swimming competitively,” says Soman, 54, after the March launch of his autobiography, Made in India: A Memoir, written with Roopa Pai.

National level-swimmer-turned-supermodel-turned-actor-turned-runner-turned-entrepreneur, Soman has worn multiple hats with aplomb. Yet, he believes his life is not worthy of a book because there is no struggle or obstacle that he had to overcome. “No, I am still not convinced that my life deserved a book,” he laughs. Publishers Penguin Random House India approached him with a proposal five years ago, but he declined as he had “forgotten most of his life anyway”.

Around the same time, he came across short snippets posted by Pai on Facebook about Indian sportswomen participating in the 2016 Rio Olympics. Impressed with the content, he commented “you write very well!” on one of the posts. Pai, who has authored multiple books, including The Gita For Children, remembers getting a ‘friend request’ from Soman one day. “To my surprise, it was him… but that was not the end of the story,” she says.

A year later, when Soman relented to Penguin’s persistence, he wanted Pai to write the book. “The challenge was exciting and the fact that Milind had asked for me particularly sealed the deal,” says Pai, who had over a dozen face-to-face interactions with Soman for over a year, each lasting 3 to 4 hours. The book was written in three months, but Soman took 10 months to read the manuscript. “One of the toughest parts was getting him to read the book… he could have finished it in three hours,” jokes Pai.

Soman chose Pai to co-author his memoir after reading her posts on Facebook

Soman chose Pai to co-author his memoir after reading her posts on FacebookMade in India: A Memoir gives you a glimpse of Soman finding succour in Enid Blyton’s books and Star Trek, his love for Tarzan, his uneasy equation with his late father Prabhakar—a pharmacologist—his swimming prowess, modelling stardom, acting career and running escapades. It also sheds light on his days as a junior cadre of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). For nearly two years, Soman would be at the RSS shakha every evening for a couple of hours with 20 to 25 children his age, marching in khaki shorts, doing yoga, exercising in a traditional outdoor gymnasium and chanting Sanskrit verses.

“It was for me a playschool kind of a thing. Nobody ever spoke about religion, casteism or racism. There was nothing negative. Even the camps we went to were about inculcating discipline, teaching respect, loving your country and being a proud Indian. It was what every boy needed to learn,” says Soman, an alumnus of the MH Saboo Siddik College of Engineering in Mumbai.

Usha is annoyed with the criticism that Soman has received of late for being affiliated to the RSS as a boy. “It is an uncalled-for controversy. Does a nine-year-old even know the ‘P’ of politics? In those days, the RSS espoused uniting people and loving one’s country,” she says.

She was the pillar of Soman’s strength since he maintained only “basic, superficial communication” with his “idealist” father. “I never thought I could have had any other kind of relationship with him. But he was proud of everything that I did. He used to make clippings of all the news about my swimming and make albums of them. I just didn’t spend that much time with him,” says Soman, the only boy among four siblings.

Growing up, he relished swimming because it gave him time with himself. “I was happy being alone. I love my own company. I enjoy it as I have a lot to think about which is not negative,” says Soman. It helped that he was good at his sport. He won his first national-level medal at 10; in 1984, then 18, he became a national champion in the 100-m breaststroke and defended the title for four years thereafter. His selection for the 1986 Seoul Asian Games was a given, but he was shocked to see his name missing from the list. Soman attributed his omission to “politics” and lashed out at his Indian coach immediately after. “That was a terrible experience for me. It made me a lot more cautious about how I interact with people. And made me more aware of the play of position,” he recalls. The disappointment led to Soman giving up competitive swimming at the age of 23.

In his book, Soman writes that serendipity is his middle name. Nothing sums it up more than his foray into modelling. His friend and co-swimmer Bijoy Jain was approached by model coordinator Rasna Behl to audition for a print advertisement for Graviera Suitings. Since he could not go for it, he asked Soman to give it a shot. He was rejected for “being too young to carry off a suit”, but called for another opportunity three weeks later. “I shot for a couple of hours for a shirting ad for Thackersay Fabrics and was paid ₹50,000 for it in 1989. I gave that money to my mother who asked, ‘Why are they paying you so much? Are they stupid?’” recalls Soman.

Around the same time, Jain introduced Soman to designers at Ensemble, a luxury designer store in Mumbai’s Naval Dockyard area. He was selected to model for Rohit Bal’s first-ever menswear collection, and thus began his journey as a supermodel. “There were only two models who had that kind of magnetic personality: One was Milind Soman, and the other was Arjun Rampal. Milind was always disciplined, he never got carried away… he had a presence, maturity and finesse. He was so sensational that once you saw him, you couldn’t forget him,” says fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani, one of the partners of Ensemble.

Nothing, however, could match the frenzy Soman created by stepping out of a wooden trunk, bare-chested, in Alisha Chinai’s ‘Made in India’ music video in 1995. He’s there for barely 55 seconds in the 4.19-minute song, but such has been its impact that he admits: “It catapulted me to stardom in another way, in another world.” It’s ironical that he found the concept “tacky and cheesy” when it was narrated to him.

Chinai had met Soman socially a few times earlier and had suggested him for the video. “Milind is a little elusive, but I sweet-talked him into doing it. He agreed, but wanted the wig that I wear as a queen in exchange,” recalls Chinai, who cannot imagine anybody else in the song. “Milind looked like a Greek God… he was the epitome of Mr Made in India. He was perfect eye candy.”

Soman had to shoot for only half a day, but he was exasperated by the end of it. “The last bit where he lifts me and walks away… that was hysterical. I was too heavy and it was a long walk, and he kept tripping on his dhoti and half-dropped me,” laughs Chinai. “But ‘Made in India’ was magic. What was amazing was our combustible energy on screen. Actually, this is his only claim to fame. There’s nothing else.”

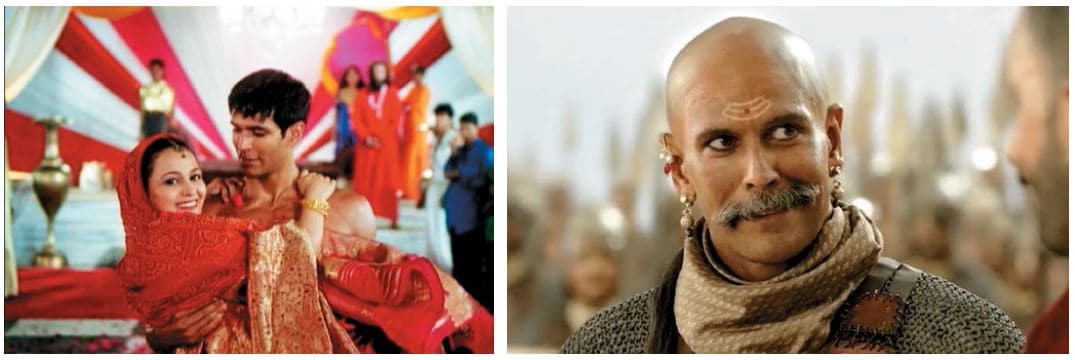

A still from ‘Made In India’ (left), the song that made Soman a household name, and Bajirao Mastani, among his latest films

A still from ‘Made In India’ (left), the song that made Soman a household name, and Bajirao Mastani, among his latest films

As an actor, Soman did not enjoy the success that he had as a swimmer and model. He attributes it to his lack of seriousness. “I enjoyed acting, but I wasn’t invested in my film career at all. For me, it was like a holiday,” says Soman, who starred in A Mouthful of Sky, Captain Vyom and Sea Hawks—all television series aired on Doordarshan—and films such as Tarkieb, Agni Varsha and Bajirao Mastani, among others. In fact, he walked out of the 1992 hit Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar after a couple of shooting schedules because the crew did not feed him enough. “I didn’t get along with the unit and had a showdown,” he says.

Soman has steered clear of controversies and conflicts. The only time he courted trouble was when model Madhu Sapre and he posed nude with a python between them for an advertisement for Tuff shoes in 1994. Political parties gave lectures on morality and women’s organisations handed stacks of sarees to Sapre’s father. A public interest litigation was filed for obscenity and a case registered under the Wildlife Protection Act for the illegal use of a python. The case was dismissed 14 years later, in 2009.

Usha was in Africa when she saw the ad in one of the international magazines. She called to tell her son that it was a beautiful picture. “The concept was nice. There was no need to paint it with a moral brush. But it upset people and ended up being a headache for us,” she says.

The model says the case did not affect him, but he’s glad it’s over. “It’s a relief because we don’t have to pay the lawyers anymore. For 14 years, nobody knew that the case was on, except us. We never went to court anyway, but it was a pain,” says Soman. In fact, a couple of years before the Tuff ad, Soman had shot in the buff for designer Suneet Verma and photographer Bharat Sikka at the Ridge in Delhi. The Delhi edition of the Saturday Times—a weekend supplement of The Times of India then—had even published the photo. “That did not elicit any protest,” says a bemused Soman.

Of late, he is trolled for marrying a woman 26 years younger, but Soman remains unperturbed. “I never looked for validation since I was a child,” he says. “I don’t like to put up a façade because it is hard work.” People who have collaborated with him concur. “He’s a real person, grounded. He’s not in the rat race for fame or success. He’s got an attitude, but it works for him. He’s a little self-centred because he knows he’s good and so he doesn’t care,” says Chinai, who also shot music videos such as ‘Prized Possession’ and ‘Tu Jo Mila’ with him.

Pai had no clue what to expect from a celebrity like him, but Soman charmed her in their first meeting. “Not with his looks, or by being thoughtful and putting me at ease, but just by being himself, someone so comfortable in his skin, so aware of who he was, and so content with his life choices,” she says.

In the last decade-and-a-half, Soman has become synonymous with fitness. The man who would once smoke 30 cigarettes a day has now run the Mumbai Marathon (21 km and 42.2 km) for several years, completed the Ironman Triathlon (3.86-km swim followed by a 180.25-km bicycle ride and 42.2-km run) and the Ultraman challenge (10-km swim, 148-km bicycle ride on Day 1; 275-km bike ride on Day 2; 84-km run on Day 3). He’s also started the Pinkathon—a marathon for women—and is the director of Speaking Minds, an international speakers’ bureau. “He’s busier now than he was when he was a model,” says Usha.

Soman is only following his philosophy: “I don’t overstep. I know exactly what I can do, what I am comfortable with, that takes me ahead. I don’t jump 20 steps… I jump one step at a time, but I keep jumping.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)