Paani ka passbook: How drought-hit Marathwada villages are budgeting every drop

Farmers in the Maharasthra region are leading the efforts to practice community-based water governance

Farmers in Kolegaon village have put up a water budget board that tracks water availability and consumption

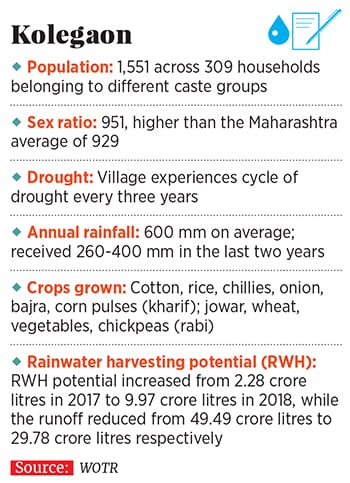

Farmers in Kolegaon village have put up a water budget board that tracks water availability and consumptionDushkaal Aasmani Nasun Sultani Aahe’, goes a popular Marathi saying: Drought is not because of lack of rain but because of poor governance. Narayan Deorao Susar, 70, a farmer in Maharashtra’s drought-affected village of Kolegaon, claims that no one understands this better than him. Over the years, he has seen government officials turn a blind eye to the fact that water conservation policies with respect to farming exist only on paper. Through the years, water-intensive crops were cultivated in his village because people did not know better. When rainfall proved insufficient, groundwater was extracted indiscriminately. When crops failed nonetheless, farmers struggled with debt. Many migrated to cities in search of work.

Susar realised that only participatory planning involving members of his community and the local gram sabha (village council) could make a difference. So, in 2016, with the support of Pune-based non-profit Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR) that was working to improve water management in Kolegaon, Susar and a few like-minded farmers led the efforts to practise community-based water governance.

To start with, farmers in this village in the Marathwada region started maintaining a metaphorical ‘Paani ka Passbook’ that tracks water consumption vis-a-vis its availability.

Outside the premises of the village temple is a huge board resembling an accountant’s ledger, tracking the movement of water. Twice a year, in May and October, the gram sabha takes stock of the water availability and consumption numbers, analysing data collected by designated villagers—called jal sevaks—on a monthly basis. This way, every drop is accounted for, and every household is held accountable for water usage.

“Last year, we received less than 260 mm of rain as opposed to the annual average of 600 mm, leading to a water deficit. But the first few days of rain look good this year, so we will be able to make up for the loss,” says farmer Ishwar Wagh.

It is the first week of July, and he points to the board behind him, where, on the left is an estimation of how much water the village receives from various sources and the right side accounts for where the water is spent. As on the first week of July, the village had received almost 101 crore litres of water, collected via soil percolation, groundwater recharge mechanisms, cement canals and earthen bandhs. The board indicates that villagers need almost 5 crore litres for personal and animal consumption annually, and 2 crore litres for other occupations. This leaves 84 crore litres for farming purposes. However, the farmlands, spread across 458 hectares in the village, will require at least 282 crore litres of water.

Farmers are not worried. Last year, even with the scanty rainfall, they had managed to shake off their dependence on tankers to secure minimum water needs. “This is different from, say, five years ago, when we required tankers from February despite receiving over 500 mm of rainfall,” says farmer Tejrao Ballari Gawande.

What made all the difference, he says, is learning to recharge shallow and deep aquifers, and preventing water runoff. Kolegaon has arrested close to 13.61 crore litres of water through its seven check dams, four earthen nala bandhs, 18 farm ponds and 412 hectares of compartment bunding.

Farmers also planned crops according to water availability. “For example, instead of water guzzling kharif crops like rice and onion, we cultivate soybean, chillies and moong. We follow it up with either no rabi crops, or ones with low water requirement like jowar and harbara (gram),” Gawande says. A few other farmers like Wagh have turned to zero-budget or organic farming, using minimum water and chemical fertilisers. The water budget board also lists how much water per hectare each crop requires for cultivation.

Making it count

Abhijeet Kavthekar, assistant manager, WOTR, says jal sevaks are trained to use manual rain gauges for accurate measurement of water, and monitor the open wells and borewells on a monthly basis. “A committee called the Village Watershed Management Team (VWMT)—comprising farmers, landless labourers, women and other stakeholders—has been created to guide villagers. They bring about a mindset change that water security does not always require capital-intensive structures or policies. One just needs to know how to manage what one already has.”

Villagers of Kotha Jahagir raise money to maintain the community percolation tank. In 2017-18, they rejuvenated one earthen nala bandh and two cement nala bandhs

Villagers of Kotha Jahagir raise money to maintain the community percolation tank. In 2017-18, they rejuvenated one earthen nala bandh and two cement nala bandhsChhaya Parameshwar, the first woman in Kolegaon to become a jal sevak, in January, says villagers must be made aware of government policies and other local rules. She is referring to gram sabha-imposed regulations like setting up a borewell extraction depth limit of 150 feet, and a ban on directly lifting water from harvesting structures. “One is also required to plant trees,” she says.

About 10 km away, the smaller village of Kotha Jahagir narrates a similar story. The water scarcity situation here seems a tad more severe than in Kolegaon, with the village requiring up to 381 crore litres of water for farming against an availability of about 128 crore litres. Apart from water budgeting, this year, the village constructed five new harvesting structures like cement nala bandhs through the Jalayukt Shivar Abhiyaan scheme launched by Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis in December 2014 to make Maharashtra drought-free by 2019.

“Villagers raise money for maintaining the community percolation tank every year. In 2017-18, they rejuvenated one earthen nala bandh and two cement nala bandhs to create an additional harvesting capacity of 5,602 cubic metres,” says Kavthekar. “About 70 percent farmers have moved from flood to drip and sprinkler irrigation. This has saved over 7 crore litres of water in three years.”

The village is also part of a larger aquifer mapping project undertaken by WOTR—on the lines of the Maharashtra Groundwater (Development and Management) Act, 2009—where data is being collected to ensure equitable distribution of groundwater from underground aquifers, which are spread across multiple villages.

Even though water is a scarce resource, farmers of Kotha Jahagir show willingness to share it. “If one village extracts more water from aquifers, someone else will be deprived of it. So we are creating an advisory committee with senior decision-makers from 14 neighbouring villages, who will decide how water should be distributed,” says cotton and chilli farmer Sukhram Iche. “Now that we are learning to manage water, we are willing to share it too.”

Scalable community conservation

Experts believe that such mindset changes are the starting point for people to successfully manage water resources in the long run.

Lancy Fernandes, head of training at Paani Foundation, says a huge challenge is to make people accept that water is a collective and not a private resource. “Compared to uniting a village for water conservation works, uniting villagers to collectively manage water resources is more difficult. This needs designing of separate trainings, creating special videos and motivating villagers who have done water conservation to graduate towards water management.”

The Foundation, founded by actor Aamir Khan to fight drought in rural Maharashtra, has launched the annual Satyamev Jayate Water Cup (in which WOTR is a knowledge partner). This six-week-long competition has villages contending for cash prizes by showcasing impactful application of rainwater harvesting practices. Villagers are also trained in watershed management. Starting with 116 villages across three talukas in 2016, about 4,025 villages across 75 talukas in Maharashtra participated this year.

Fernandes says such initiatives could be scaled up to other villages, provided there is a field team of skilled trainers and coordinators. “Without such a team, the transformation of fractured villages to unite and make their own destiny will not take off. Any scaling up which is bureaucratic or primarily managerial will fail,” he says.

Ayyappa Masagi of the Water Literacy Foundation that engages in watershed management practices says voluntary organisations require government support to scale up and that the political will is missing. “It is almost as if the government wants villagers to continue being dependent on them. This attitude must change,” he says. SB Dalvi, village development officer at Kotha Jahagir, believes that the government “is not doing enough” and that it should “work with the people to implement solutions”.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his first Mann Ki Baat address after forming the new government, acknowledged how “people in village after village resolved to accumulate every single drop of water”, saying they have been “raising a water temple in their respective villages”. Many thousand kilometres away from the seat of power in Kolegaon, Susar is unaware of Modi’s words. For now, the chilli, cotton and vegetable farmer has made his field rain-ready by digging a recharge pit, creating ways to arrest more water and using the resource judiciously. “When it comes to water, rather than depending on anyone, we have to take charge of our own destiny and act. Nothing else will work.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)