The economic potential of women self-help groups

Leveraging the potential of women self-help groups for economic revival calls for bridging the digital divide, building scalable programmes, and creating targeted interventions for the most vulnerable

Jugni says she is “as illiterate as a buffalo”, speaking in Hindi as she lays out a plastic mat next to a farm where a few goats are tied to trees. She belongs to the Garasia tribe in the Sirohi district of Rajasthan, and is meeting with five other members of her self-help group (SHG) in July after a gap of four months. Their functioning had come to a complete halt during the lockdown, and there was a lot of work to do. “We could not go to the market to sell our produce, and used to give it to a middleman who collected it from our homes. So the bhindi [okra] we used to sell for ₹20 a kilo went for as low as ₹7 per kilo during the lockdown,” she says, over a video call on a borrowed smartphone. She owns a feature phone, and is just warming up to virtual meetings.

Jugni, one of the founding members of the Chetna Rani Mahila SHG, says she has come a long way from getting women to save ₹10 each week to be able to get electric supply to their fields two decades ago. Today, the 13 women in her group are able to save up to ₹80,000 a year and take small loans from local cooperatives for their farming and animal husbandry ventures. Their financial literacy, visible in the meticulous accounts maintained in notebooks, has been learnt entirely through experience. Digital knowledge never seemed like a priority, until now, and Jugni is willing to learn, if adapting to change is what it takes to survive in the wake of the pandemic.

“Most people have a feature phone and a bank account in these villages. Only a few members in about 150-odd women’s groups out of 500 in this area are educated and own a smartphone. After the movement of SHGs was severely restricted during the lockdown, we are working towards piloting a digital literacy project among these 150-odd groups in August,” says Richa Audhichya, a social activist who works with local women SHGs through her organisation Jan Chetna Sansthan. “It’s time, because these women can’t stop just because there is uncertainty due to the pandemic.”

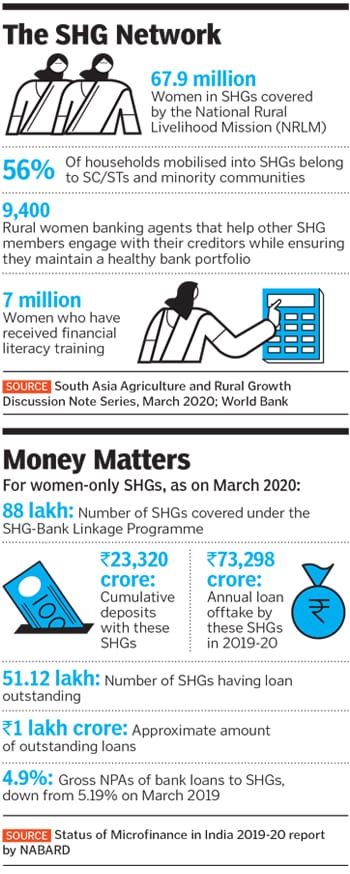

India’s network of rural SHGs—where women from similar socio-economic backgrounds pool in their savings and manage their credit interests with the principles of solidarity and mutual interest—has grown over the years, enabling women to be enterprising, take risks, earn financial independence and seek greater participation in the decisions taken in their homes and villages. India has over 68 million women working as part of SHGs, and like most industries and sectors they are turning the Covid-19 challenge into an opportunity.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)