Bengaluru: City of a thousand lakes, once more

A community of skilled well-diggers is taking Bengalureans back to basics to make them water-secure

Water expert Vishwanath (third from left) has been working with the well-digger community for over a decade

Water expert Vishwanath (third from left) has been working with the well-digger community for over a decadeThe most popular story about Sarjapur is how this region in suburban Bengaluru was offered as a jagir by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb to the Mysuru Wadiyar dynasty in the 17th century. Today, Sarjapur’s tall, tony residential buildings and its unceasing traffic woes narrate how Bengaluru has expanded beyond its means, without planning or preparation. An anomaly nestled in the middle of this IT boom is the village of Bhovi Palya.

Most people in this village are holding on to the past, carrying on with a profession that continues to be threatened by Bengalureans’ growing fascination with borewell extractions and tankers for water supply. Now that India’s Silicon Valley stands to face acute water scarcity, members of this community have found a new lease of professional life. Bhovi Palya is a settlement of traditional, skilled labourers who dig wells for a living. In Kannada, the word Bhovi loosely translates as ‘well’ or ‘earth-digger’.

With help and training from water expert Vishwanath Srikantaiah, this community of well-diggers—comprising about 750 families scattered across 15 settlements on the periphery of Bengaluru—is going to various water-scarce localities of the city to build rainwater harvesting (RWH) structures, and creating awareness about open wells and recharge pits as water conservation mechanisms. Their efforts have intensified after a doomsday call from government think tank Niti Aayog, whose 2018 Composite Water Management Index (CWMI) report suggested that Bengaluru is among the first few cities that might completely run out of groundwater by 2020.

Ramakrishna, a fourth generation well-digger, tells this journalist how his great-grandfather was among the first settlers of Bhovi Palya almost three centuries ago. Bengaluru, then, was known as the city of a thousand lakes, with its water needs met by a series of well-connected man-made tanks. These structures were interconnected by a network of canals (which came to be called ‘rajakaluves’) that captured rainfall and transferred excess water from higher to lower level tanks. Each house in the city had an open well. “Well-diggers were sought after to build these structures, which also helped replenish underground aquifers and maintain groundwater levels,” says Ramakrishna.

Back to Basics

The creation of new residential localities in Bengaluru following the bubonic plague of 1898 led to a search for water bodies outside the city to satisfy the water requirements of the growing population. Over the years, authorities have just kept going further and further away in this search. Water was initially pumped from the neighbouring Hesaraghatta lake. A dam was then created on the Arkavathi river about 32 km away as part of the Thippagondanahalli scheme in the 1930s. Today, most of Bengaluru’s water requirements are met by the Cauvery scheme implemented in the 1970s, which involves transporting water from a river located about 100 km away.

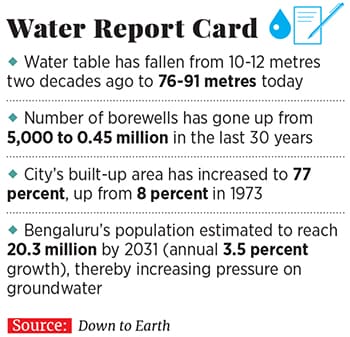

At the same time, Bengaluru’s water table has shrunk from 10-12 metres to 76-91 metres in the past two decades, while the number of extraction wells has increased from 5,000 to 0.45 million since the late 1980s. According to Down to Earth, a publication of the Centre for Science and Environment, India’s IT city seems to be following in the footsteps of Africa’s Cape Town, which almost ran out of water in 2018 and is currently slowly rebuilding its reserves. Bengaluru too might run out of potable water if preventive measures are not taken immediately. Given this prediction, the Karnataka government is now planning to draw water from the Linganamakki dam, located 425 km from the city, at a cost of approximately ₹12,000 crore.

Experts, however, point out that instead of such capital-intensive methods of sourcing and supplying water, Bengaluru could easily be water positive if the government implements existing policies that make RWH mandatory in all households, and creates awareness about cost-effective solutions like open recharge wells.

“Bengaluru receives 1,450 million litres per day (mld) of water from the Cauvery and will get another 775 mld in the coming year as part of the fifth stage of the Cauvery scheme. This is sufficient for the city if distributed equitably. But currently, about 30 percent of the population does not have access to this water,” says Vishwanath. Another major challenge, he explains, is that groundwater could account for anywhere between 400 to 700 mld of water, but there is no exact number because the borewells are not counted or metered. “So we do not know how much we are extracting.”

Bengaluru, with a population of over 1.2 crore people, receives an annual rainfall of about 970 mm. “According to the Central Ground Water Board of the Ministry of Water Resources, only 10 percent of this goes to the underground aquifers, while the rest is just run-off,” says Vishwanath, who is the co-founder of Biome Environmental Solutions. This run-off is wasted in stormwater drains and accumulates at low-level points to cause urban flooding.

To counter these challenges and present a big picture solution to Bengaluru’s water crisis, Vishwanath has launched the Million Recharge Wells project, which aims to capture up to 50 percent of the total rainfall in aquifers. To achieve this, Vishwanath and the well-diggers, since 2018 have not only been convincing homes and apartments to have independent RWH systems and recharge wells, but are also creating public recharge structures. They have rehabilitated seven existing open wells in Cubbon Park, out of which five are already in use.

“We are digging 65 more recharge wells in the Park, out of which 37 have been completed,” Vishwanath says. “If we achieve this goal [of trapping 50 percent rainwater], then we will be able to produce almost the same amount of water that is being extracted from the Cauvery. But rather than being pumped from 100 km away, this water will be below our feet, it will be decentralised and at 1/10th the cost and energy.”

The Rainbow Drive gated community in Sarjapur spread across 83 acres is an example of how 280 independent homes are surviving primarily on RWH and natural recharge mechanisms built by the well-diggers. Since the piped Cauvery water supply from the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) could not reach their homes, people started sourcing water from a borewell, only to realise that extracting water without replenishing it is an unsustainable proposition.

KP Singh, a resident of Rainbow Drive, explains that the society has made it mandatory for every home to have a RWH system, without which a water connection would not be provided. “Every home has a storage tank that collects between 6,000 and 20,000 litres of water, depending on the size. The overflow goes to the recharge pit. We have recharge wells outside the society to collect rainwater, and treat up to 70,000 litres of waste water on the premises every day.” Singh, a retired IT professional, explains that these practices make at least 500 kilolitres of water available to every family per day all year long. The requirement of water tankers too, is few and far between.

Policy Push

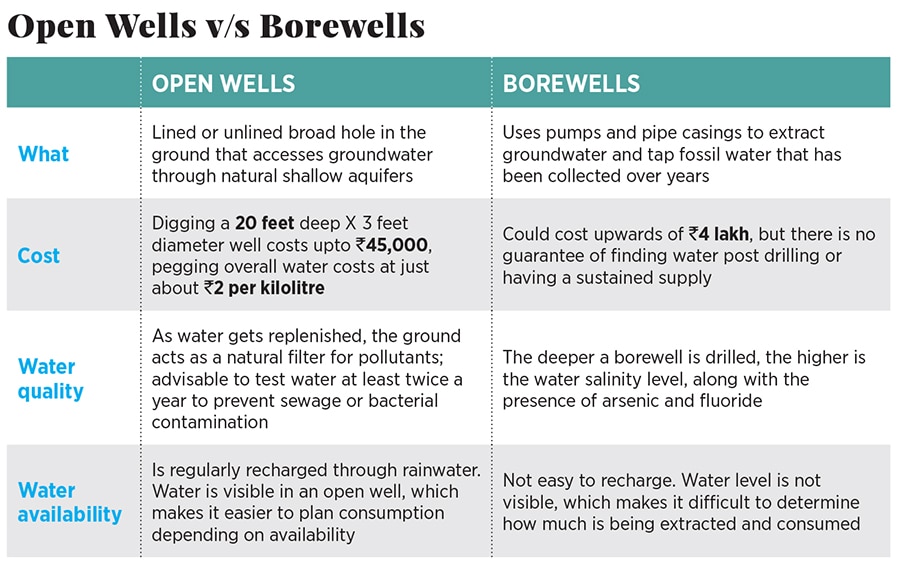

Awareness about capturing rainwater is certainly increasing, says Ramakrishna, the well-digger. According to him, every member of his community now digs up to three open wells (usually 3 feet in diameter and 20 feet in depth) a month, each typically earning them anywhere between ₹35,000 and ₹50,000 depending on the depth of the well. “In homes with less space, we build recharge pits. I build up to 15 every month. We even get requests to clean wells, which gets us between ₹3,000 and ₹6,000 per well.”

He adds that people who had left well-digging because of slowing demand to pursue other occupations—such as being security guards, cooks or cleaners in the IT companies and residential complexes around their village—are now slowly returning to the profession. “Now, people who thought this was a dying profession are reconsidering,” Ramakrishna says.

Anand Kumar and his wife Lalitha, both well-diggers, regularly follow up with people with open wells and encourage others to take better care of the wells / recharge pits in their respective premises. “We get most demand from areas like RT Nagar, Yeshwanthpur, Malleswaram, Vidyaranyapura and JP Nagar. People have started believing that just conserving and managing rainwater could give them all the water they need,” says Kumar.

Vishwanath, however, says that Bengalureans could do much more at the individual level. Official statistics from the BWSSB show that he’s right. Every year, over 75,000 households in the city pay a 50 percent penalty on their monthly water bills because they have not installed RWH systems as mandated by law. So, while 1.25 lakh buildings are compliant, the BWSSB continues to make over ₹12 crore annually in fines because buildings in Bengaluru are not harvesting water.

Harini Nagendra, professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University, explains how community wells in Bengaluru have drastically reduced from about 1459 in the 1880s to less than 49 in 2015, mainly because they were built-over. According to her, policy planning with regards to water must critically engage with the city’s changing terrain and topography.

She says: “The government must work with the community to protect wetlands that soak rainwater long enough for it to percolate into the ground, thereby preventing run-off. Building of public recharge wells must also be complemented by large-scale planting of trees in the right places.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)