- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Tackling India's oxygen emergency: Can there be a timely, cost-effective solution?

Tackling India's oxygen emergency: Can there be a timely, cost-effective solution?

Hospitals and individuals are raising an SOS, civil society is on its toes, courts are stepping in, and industries are diverting resources for medical use. As caseloads increase, Forbes India explores the way forward to ensure timely and cost-effective access to oxygen for Covid-19 treatment

Divya writes about gender, philanthropy, startup and workplace trends, and business from the lens of its impact on people. She is keen to find interesting stories and new ways of telling them. A journalism graduate from Mumbai who was previously with The Economic Times, Divya is also an editor and proof-reader. Outside of work, she likes to travel, read books, drink hot chocolate, and endlessly watch, read and talk about cinema.

- For businesses, sustainability should be a leadership challenge, not a cost problem: Rajeev Peshawaria

- Philanthropy for mental health should focus more on community-led models

- I was never taken seriously as someone who can build a business: Masoom Minawala

- Indian companies should focus on high value manufacturing: Vijay Govindarajan

- Roop Rekha Verma's unwavering fight to uphold constitutional values

A public notice hangs outside Shanti Mukund Hospital notifying shortage of oxygen beds, on April 22, 2021 in New Delhi, India. Hospitals in several cities are facing an acute shortage of medical oxygen as Covid-19 cases rise rapidly.Image: Amal KS/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The HBS Hospital in Bengaluru was down to the last 1.5 hours of oxygen supply on April 22.

Related stories

“The traffic police stepped in and created a green corridor, which helped us pick up and deliver oxygen supplies in a record 40 minutes. We reached the patients in the nick of time, when there was only 15 minutes of oxygen supply left,” says Masood. A green corridor is where traffic signals en route the hospital are controlled manually and kept green for an ambulance to pass. It is usually used in the case of an urgent organ transplant.

Masood, who runs six oxygen centres in Bengaluru as part of the non-profit, says the 55-odd patients in HBS Hospital require 10-12 oxygen cylinders every day, with the capacity of one cylinder being about 200 litres. Covid patients need oxygen therapy when the oxygen saturation in the blood falls below 94 percent. “In the case of severe Covid cases, when the oxygen saturation level in the blood starts dropping, people consume at least 60 to 70 litres of oxygen per minute,” says Masood. Across Karnataka—which is heading for a lockdown this weekend—the state drug controller projects a total demand of 1,643 tonnes of oxygen per day across hospitals, while the current production capacity is around 812 tonnes.

While this is the case in Karnataka, regions including Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh have also seen a big deficit in oxygen supplies to hospitals over the past few days. The SOS or calls for help on social media have somewhat reflected the scale of panic that people and the health care system is dealing with: On April 23, Max Healthcare hospitals in Saket, Delhi, treating close to 700 Covid patients, were still awaiting fresh oxygen supplies and had only less than an hour’s supply left. The day before, Fortis Healthcare had to send out an SOS to PMO India and other Union ministers as its hospital in Haryana had only 45 minutes of oxygen supply left. On the same day, the Shanti Mukand Hospital in Delhi requested doctors to start discharging whichever patient could be let go, as they had only about two hours of oxygen left.

Countless individuals have also been taking to social media to request for urgent oxygen supplies for their friends and family members suffering from Covid-19. While community volunteers and civil society members have been actively working to fulfill as many requests as they can, over the past two days, the Delhi High Court and the Supreme Court have also stepped in, with the latter on April 22 seeking a detailed plan from the Centre for uninterrupted supply of oxygen and essential drugs. The Centre has invoked provisions under the Disaster Management Act, 2005, to disallow authorities to stop or divert vehicles carrying oxygen. This was done after hospitals in Delhi and UP complained that the Haryana government had stopped oxygen vehicles in transit, and PM Narendra Modi stressed on faster, uninterrupted transportation to the states.

The spike in oxygen demand comes in the wake of increasing Covid-19 cases and deaths, with India reporting a record global single-day jump on April 22, with more than 3,14,000 new infections over a 24-hour period, and the number of deaths at 2,104. As of April 22, the total confirmed cases of Covid-19 in India had crossed the 1.5 crore mark, resulting in the deaths of 184,657 people, as per the health ministry.

“Oxygen beds in health care facilities are under a great deal of stress. In the second wave, the sudden surge of cases is multifold compared to the first wave. There is rapid progression of the disease, more commonly seen now in the younger age groups. There is high infectivity and transmission of mutant variants added to this second wave,” says Dr Venkat Raman Kola, clinical director—department of critical care medicine at Yashoda Hospitals, Hyderabad.

The hospital group has up to 1,000 beds for Covid-19 patients across Hyderabad that have been operating at full capacity over the last two weeks, Kola says, anticipating a shortage of liquid oxygen supply to their oxygen plants given a seven-fold increase in demand for liquid oxygen across the country. “Eighty percent of our Covid patients are on oxygen and others come with miscellaneous complications.”

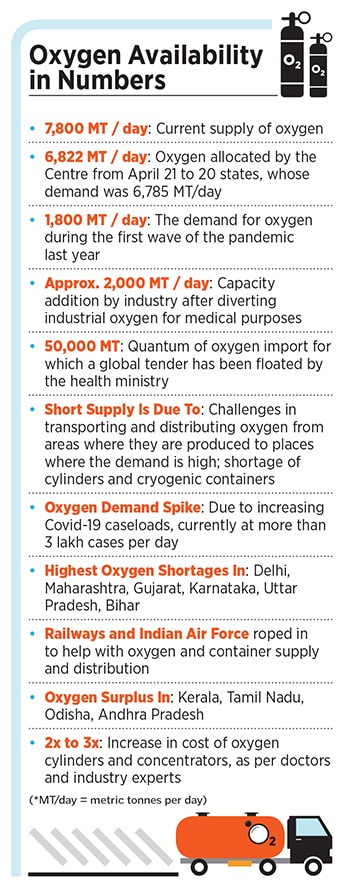

While PM Modi has said that the supply of oxygen must be ensured in a “smooth, unhindered manner”, the health ministry has also floated a global tender to import 50,000 metric tonnes of oxygen.

“Against the present demand from 20 states of 6,785 metric tonnes per day of liquid medical oxygen, the government of India has from April 21, allocated 6,822 metric tonnes per day to these states,” said the government, adding that present availability of liquid medical oxygen has been increased by about 3,300 metric tonnes per day after private and public steel plants, industries, and oxygen manufacturers have diverted their resources for medical use. The total oxygen production capacity of the country is at 7,800 metric tonnes a day.

Getting Rid of Supply Bottlenecks

Increasing Covid-19 caseloads and a broken supply chain are at the heart of the oxygen shortage India is staring at. As prices for oxygen cylinders shoot up in the wake of a shortage and limited access, industries have also stepped in to meet this growing demand, under an instruction from the Centre to divert industrial oxygen toward medical usage. Industrial oxygen has to be processed to about 95 percent purity for it to be used for medical purposes. A detailed explanation on how medical oxygen is made can be found here.

As per the ministry of steel, twenty-eight major public and private steel plants are supplying close to 1,500 metric tonnes of medical oxygen every day across the country. Reliance Industries has a ramped-up capacity to produce about 700 metric tonnes of liquefied oxygen, as per media reports, while the capacity is at 600 metric tonnes for Steel Authority of India (SAIL), and JSW Steel is at 600 metric tonnes.

Oxygen is manufactured in industrial plants away from cities and is transported in large cryogenic cylinders and bottled closer to the source for medical oxygen cylinders. A source who is aware of the supply situation, and did not want to be identified, said that the bottlenecks are at oxygen plants and in shortage of small cylinders. Cryogenic tankers needed to transport the oxygen and smaller cylinders are also in short supply. The Tata Group, on April 21, announced the import of 24 cryogenic containers to transport liquid oxygen. The import price for a 10,000 litre oxygen vessel / container is estimated to be around Rs18-20 lakh.

Cylinder manufacturing is a regulated activity that requires licences from the Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation [department of the government] and so it is not possible to set up a new plant overnight. Existing players will have to produce as much as they possibly can for the next few months, the source explains, adding that there will also have to be some imports of the larger cryogenic cylinders to transport fluid oxygen—no one knows how long this would take and how many are required—these are usually built to suit against firm orders and have a 30-60 day order lead time.

“We have a ready availability of 528 tonnes of oxygen at our Angul plant in Odisha, and we can produce 100 metric tonnes every day to bridge the gap wherever we can. But we have been waiting for users [government authorities, hospitals] to send tankers to transport it,” VR Sharma, managing director at Jindal Steel and Power Limited (JSPL), tells Forbes India. “In the past five days, we have had only five tankers, when we have the capacity to load more.”

The government is tackling distribution bottlenecks by utilising rail, air and road transport resources. While Indian Railways have been roped in to transport oxygen in bulk from far-away supply centres, the Indian Air Force is airlifting empty oxygen tankers and reaching them to industrial units and filling stations that are providing medical oxygen. From April 23, the C17 and IL-76 aircraft are flying out with empty tankers to places where oxygen is being supplied, while filled-up tankers are being carried by road to hospitals, since they cannot be airlifted. At the same time, about 32 wagons of the Indian Army are also being used to transport oxygen.

According to Sharma of JSPL, more needs to be done. He suggests that each truck or tanker should have at least three drivers, enabling it to be run 24*7 without stops to reduce the turnaround time for transportation by road. The vehicles must have track and trace systems that are monitored by nodal agencies, and must be given the flexibility to change their route depending on real-time oxygen demand. “The GST department will need to step in here,” explains Sharma. “If a tanker is Delhi-bound from Odisha, for example, but en route the driver gets the information that requirements in Delhi have been met and oxygen is now needed in Bhopal instead, then the truck drivers cannot change their route because their invoices, documents etc. are meant for Delhi. So there must be provisions to resolve these invoice and documentation issues online through a control room set up by the government, so the tankers can be diverted to other cities as per demand of oxygen.”

Public Health Infrastructure Conundrum

Doctors and public health experts say that preparedness on the part of the government and a consistent attempt to strengthen primary and secondary health care systems by arming them with necessary oxygen supply and other Covid-19 treatment infrastructure could have helped lessen the impact of the oxygen crisis.

“A lot of people are testing Covid positive, but in the absence of primary and secondary-level health care management in place, they are rushing to tertiary facilities in a state of panic. Even if we advise them to get treated at home, they fear they won’t get beds if their condition deteriorates and therefore want to book the bed at the earliest,” says Sylvia Karpagam, a public health doctor and researcher. She says that the government has not done anything to alleviate this fear and sense of panic among people. “The government has always had a reactive approach, with zero proactive preparation. So there’s little they are able to do to assure people. And because of this hospitals have had to reach out to volunteers and the community for oxygen supply, which should not have been the case.”

Increasing Covid-19 cases are also leading to a growing clamour for oxygen and hospital beds in the country. Representative image of a Covid-19 patient waiting for admission at LNJP Hospital in DelhiImage: Amal KS/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The panic and the resultant hoarding of oxygen is resulting in both shortages and uptick in prices of oxygen, says Jeenam Shah, a consultant pulmonologist with Saifee, Wockhardt and Bhatia Hospitals in Mumbai. “Many well-to-do people have at least one oxygen machine or cylinder kept at home just as a backup. This leads to an oxygen shortage at the local level, and the prices of oxygen cylinders and concentrators have gone up by two-three times,” he says. “The price for renting a concentrator, for instance, used to be around Rs5,000 to Rs6,000. Now it is not going below Rs10,000.” He says that while most large hospitals will manage to procure oxygen supplies, the smaller health care set-ups are much more likely to be hit.

Sharma of JSPL says that one long-term solution to continuous oxygen supply lies in building oxygen plants in every district. “For that, every hospital in every district should also have the facilities to generate oxygen, because it does not require too many raw materials.”

Health care activist Abhijit More from Pune—one of the worst-affected cities in India that recorded a spike of over 9,000 infections over the past 24 hours and has more than 120,000 active cases—agrees with Karpagam and Shah about people admitting themselves into hospitals out of fear. “There must be some gatekeeping mechanism and assessment to see if those getting admitted into hospitals really need the oxygen,” he says, adding that 6,000 to 7,000 Covid patients in Pune require oxygen support on a daily basis. “We should continue to focus on vaccination, home isolation and contact tracing. Only that can control the wave.”

India, which will open out vaccinations to over 60 percent of its 134 crore population above 18 years of age from May 1, has been slow in its pace of inoculations. Since the vaccination drive started on January 16 with health care and frontline workers, followed by senior citizens, persons with co-morbidities and those above age 45, India has managed to vaccinate about 13 crore people, with 11 crore people receiving the first dose and only close to 2 crore people receiving both doses.

Dr Kola of Yashoda Hospitals says that they are preparing to face oxygen supply constraints by curtailing high-oxygen utilising devices like the high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), which uses five to ten times more oxygen than ventilators. “Optimising oxygen usage is also done by triaging and prioritising sick patients. We are trying to procure oxygen concentrators, which can provide 5 liters to 8 liters O2 per minute, which can be used in non-ICU patients. We are planning to divert all available oxygen for ICU and Emergency department use. We have to restrict our admission to a point to avoid the shortage of ventilators for existing in-patients.”

More, who is also a member of the Aam Aadmi Party, says that over the past few months in the wake of vaccines being available, the government reduced the momentum of its plans for creating district-level oxygen plants. “The situation could have been controlled if that was not the case,” he says. “The demand for oxygen is only likely to increase because we are anticipating another peak in cases in May. We are diverting industrial oxygen, which will help, but we need to push the pedal on building district-level oxygen plants and health infrastructure.”

Dr Satish Talade, a third-year post-graduate resident of Nair Hospital in Mumbai, and the president of the Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors, says that foresight in planning and preparation will go a long way in helping distressed doctors and health care workers. “We have 800 Covid-19 beds in our hospital, almost all of which are currently occupied. Close to 70 percent of our patients need oxygen. We have been able to face these shortages simply because the administration put in all the necessary infrastructure in place to cater to increased demand since last year.”

According to him, people should take the vaccine at the earliest and even after getting vaccinated, should continue following safety protocols and physical distancing norms. “This mutation of the virus is highly infective, so people cannot afford to be careless.”

With additional inputs from Samar Srivastava