How Cropin is using AI for better, more predictable harvests

Started 12 years ago by friends Krishna Kumar and Kunal Prasad, the agri-tech venture is becoming a global powerhouse by providing granular data on the farming ecosystem

L to R: Kunal Prasad, co-Founder and COO with Krishna Kumar, co-Founder and CEO, Cropin

L to R: Kunal Prasad, co-Founder and COO with Krishna Kumar, co-Founder and CEO, Cropin

Ask Krishna Kumar about the founding story of Cropin Technology Solutions and he likes to say it was more of an emotional decision than one grounded in business logic.

It started 12 years ago with Krishna—as everyone calls him in the company—and his childhood mate Kunal Prasad deciding that they couldn’t just sit by when Indian farmers were dumping their produce on the roadside or killing themselves for not being able to repay loans. The duo had been in school together in Ranchi, prepared together in Delhi for engineering college entrance tests, and went to different colleges. They kept in touch, with Prasad working at Tata Motors, in sales and marketing—he got an MBA as well, in between—and Krishna being a techie at General Electric. In 2009, Krishna called Prasad to say he’d quit his job, and the following year Cropin was born.

It was a time when ‘agri-tech’ wasn’t a term and ‘startup’ was common vocabulary. Although ahead of their time in India, they were onto something. They figured that technology could eliminate information disparity—and thus price disparity—between, for example, what a farmer growing tomato earns in Chikkaballapur and what a consumer in nearby Bengaluru pays for it. Consequently, farmers could earn more, and food businesses—such as Mother Dairy, one of their earliest customers—would get a more predictable supply.

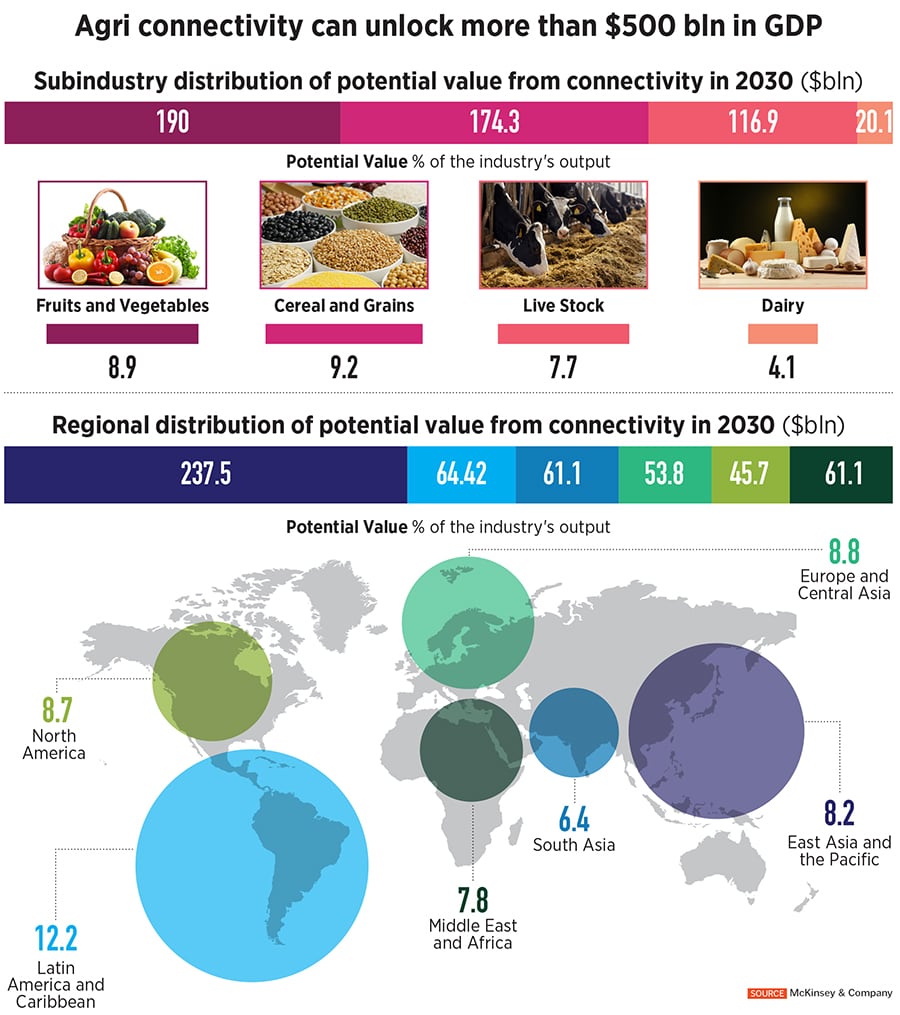

More than a decade later, their effort is about to pay off—big time. Today, the rest of the world has come up to speed, not just with cloud computing and digital technologies, but also about the importance of data-driven agriculture amid a climate crisis and rising human populations. “In the recent past, we’ve seen a lot of scale in the business,” Prasad says. In fact, he moved to Europe this March to lead the push into that market. He is also overseeing public and developmental alliances. “Digital is the new norm, and everyone now understands data-driven agriculture.”

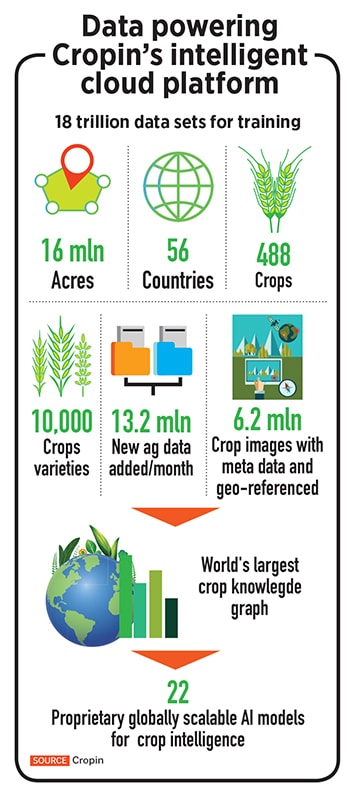

Krishna and Prasad are betting everything on building what they say will be the world’s first artificial intelligence (AI)-based cloud—everyone inside Cropin calls it ‘ag cloud’—for agriculture intelligence, by mapping land and crops on a third of the planet. They’ve already done that for 12 countries at the hyper-local level of 10 m sq. “We are very committed to marrying agricultural sciences with AI sciences,” Krishna says.

The plan is to take tech and knowhow developed in India to markets around the world. To do this, Krishna and Prasad are setting their sights on a much more ambitious project. “We are calling it the industry’s first cloud for intelligent agriculture, where we have brought all the digital apps and tools in a box,” Krishna says. This ‘Ag Cloud’ is to be launched in a matter of weeks.

The plan is to take tech and knowhow developed in India to markets around the world. To do this, Krishna and Prasad are setting their sights on a much more ambitious project. “We are calling it the industry’s first cloud for intelligent agriculture, where we have brought all the digital apps and tools in a box,” Krishna says. This ‘Ag Cloud’ is to be launched in a matter of weeks.