Against the grain, seed guns & DeHaat

After a decade of toil, DeHaat is now ready to fan out across India with its full-stack agricultural services for farmers. Can the most valued agritech player in India reap the harvest?

DeHaat founders (from left) Shashank Kumar, Amrendra Singh, Adarsh Srivastava and Shyam Sundar Singh

Image: Madhu Kapparath

DeHaat founders (from left) Shashank Kumar, Amrendra Singh, Adarsh Srivastava and Shyam Sundar Singh

Image: Madhu Kapparath

“Tumse shaadi kaun karega (who will marry you),” was a grave question posed by a concerned father in 2011. Coming from a rural farming background in Bihar, Shashank Kumar’s father knew very well what his lad needed. First was high-quality education: IIT-Delhi alum Kumar scored high on that front. Second was a non-farming life, which also meant staying away from the state. Kumar performed brilliantly on this count too. After IIT, he joined a consulting firm and spent close to three years. His parents, understandably, were elated.

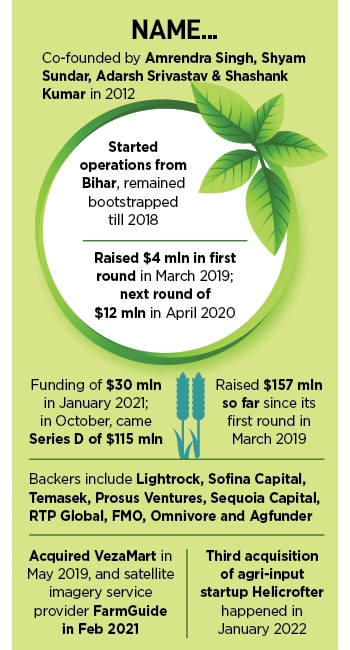

There was something missing, though. The only thing left in Kumar’s life, his parents reasoned, was to settle down and lead a happy life. Kumar, however, turned out to be an utter disappointment. He came back to Bihar, and decided to pursue a career in farming. “It was difficult for them to digest,” recalls Kumar, who went on to co-found DeHaat with Amrendra Singh, Shyam Sundar and Adarsh Srivastav in 2012.

Kumar was equally baffled. He knew there was a lot of inefficiency entrenched into every stage of the farming cycle. He had data to back his conviction. Around 80 percent of net sown area in the state was under conventional crops like wheat and paddy, which didn’t work in terms of overall unit economics for a farmer. “Why can't they grow more remunerative crops,” he wondered. He thought the solution lied in switching to high-value crops with short crop cycle.

Kumar was equally baffled. He knew there was a lot of inefficiency entrenched into every stage of the farming cycle. He had data to back his conviction. Around 80 percent of net sown area in the state was under conventional crops like wheat and paddy, which didn’t work in terms of overall unit economics for a farmer. “Why can't they grow more remunerative crops,” he wondered. He thought the solution lied in switching to high-value crops with short crop cycle.

In March 2019, the agritech startup raised its first institutional round of $4 million. Since then, it has been on a funding drive. In April 2020, came the next round of $12 million. Series C of $30 million took place in January 2021. And after nine months came its biggest round of $115 million led by Belgium-based investment firm Sofina, and Lightrock India. While Temasek co-invested in the round, existing investors such as Prosus, RTP Global, Sequoia Capital India and FMO too participated.

In March 2019, the agritech startup raised its first institutional round of $4 million. Since then, it has been on a funding drive. In April 2020, came the next round of $12 million. Series C of $30 million took place in January 2021. And after nine months came its biggest round of $115 million led by Belgium-based investment firm Sofina, and Lightrock India. While Temasek co-invested in the round, existing investors such as Prosus, RTP Global, Sequoia Capital India and FMO too participated.

And the focus is not confined to India. DeHaat has started tapping into overseas market, and what is aiding the push is technology. The startup, he claims, has built a complete traceability system and digitised the backend of farming operations. What this means is using a QR code, one can get to see that where exactly the food is coming from.

And the focus is not confined to India. DeHaat has started tapping into overseas market, and what is aiding the push is technology. The startup, he claims, has built a complete traceability system and digitised the backend of farming operations. What this means is using a QR code, one can get to see that where exactly the food is coming from.