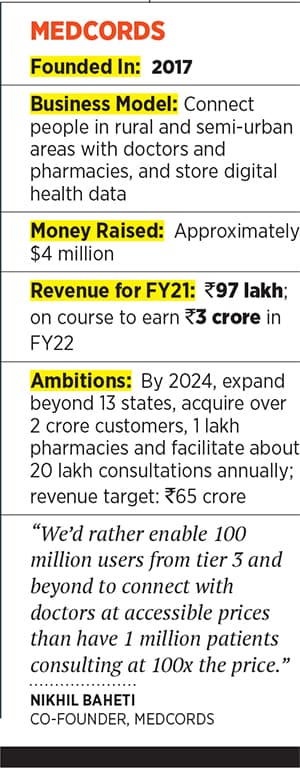

MedCords: Enabling last-mile healthcare for Bharat

First-generation entrepreneurs of the healthcare platform want to leverage technology and community-based interventions to help people in rural and semi-urban India access all their health care requirements on a single platform

(From left) MedCords co-founders Nikhil Baheti, Shreyans Mehta and Saida Dhanavath

(From left) MedCords co-founders Nikhil Baheti, Shreyans Mehta and Saida Dhanavath

Image: Arpit Jain for Forbes India

In August 2020, as the Indian economy was stepping out of the nationwide lockdowns imposed in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, Akhil Gupta’s parents in Kota, Rajasthan, tested positive for Covid-19.

The co-founder of real estate startup NoBroker.com, a Bengaluru resident, managed to get a diagnosis online, but wanted medicines to be delivered home to his parents at the earliest. He turned to a fledgling platform he had heard of, called Aayu, which guaranteed quick medicine delivery in tier 2 cities and beyond. He downloaded the app, entered the location and placed an order, following which a pharmacy nearest to his parents’ home gave them the medicines within the next two hours. “That’s when I realised the people behind this platform are building something extremely unique,” he says. By October 2020, Gupta became an angel investor in MedCords, the startup that developed the Aayu app.

Health tech in India is primarily medicine delivery or online consultation, Gupta explains, and larger startups usually dispatch medicines through a central warehouse that might take at least a day or two to deliver, depending on the location. “Plus, these larger health tech products are not available in all pin codes and in villages. This solution by MedCords works well for Bharat, for tier 2 and 3 cities and beyond,” says Gupta, who has since also subscribed to an annual doctor consultation plan on the Aayu platform.

Now, his parents avail diagnosis at home and also store all their health records digitally on the app. Medicines reach home within 10 to 15 minutes too, as the local pharmacy undertaking the delivery has developed a connection with them and is aware of the requirements. “During Covid, when you really cannot step out, this has been a boon for my parents,” Gupta says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

MedCords was also developed out of a personal need. Co-founder Shreyans Mehta’s father suffered from a slipped disc in 2014 and could not go to a hospital. While Mehta arranged a video consultation, the experience made him think about people who did not have access or know-how of such technologies. He realised how many villagers spent between ₹800 and ₹1,000 just travelling to and from cities for the most basic of consultations, and others often turned to local quacks.

MedCords was also developed out of a personal need. Co-founder Shreyans Mehta’s father suffered from a slipped disc in 2014 and could not go to a hospital. While Mehta arranged a video consultation, the experience made him think about people who did not have access or know-how of such technologies. He realised how many villagers spent between ₹800 and ₹1,000 just travelling to and from cities for the most basic of consultations, and others often turned to local quacks.  Today, MedCords has a network of about 25,000 pharmacies in 650-odd towns and cities across 13 states, and close to 5,000 doctors and specialists on their platform. They are mostly present in North and Central India. The medicine delivery follows a hyperlocal model, which reduces the delivery time to approximately 60 minutes, the founders claim. To ensure people are able to consult doctors within 30 minutes, a case is floated to all relevant specialists on the network until a doctor takes it up. The customer base is over 3.5 million people this year, up from 0.5 million in FY19 and 1.8 million in FY20.

Today, MedCords has a network of about 25,000 pharmacies in 650-odd towns and cities across 13 states, and close to 5,000 doctors and specialists on their platform. They are mostly present in North and Central India. The medicine delivery follows a hyperlocal model, which reduces the delivery time to approximately 60 minutes, the founders claim. To ensure people are able to consult doctors within 30 minutes, a case is floated to all relevant specialists on the network until a doctor takes it up. The customer base is over 3.5 million people this year, up from 0.5 million in FY19 and 1.8 million in FY20.  Health care centres in rural areas have various shortcomings, which have been exacerbated by the pandemic

Health care centres in rural areas have various shortcomings, which have been exacerbated by the pandemic