K Dinesh and family: The generous givers

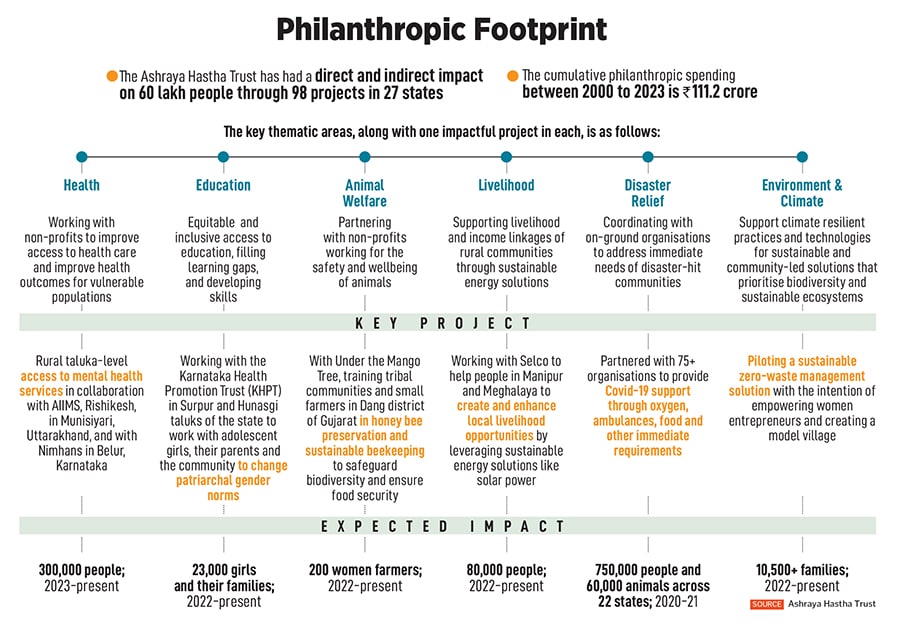

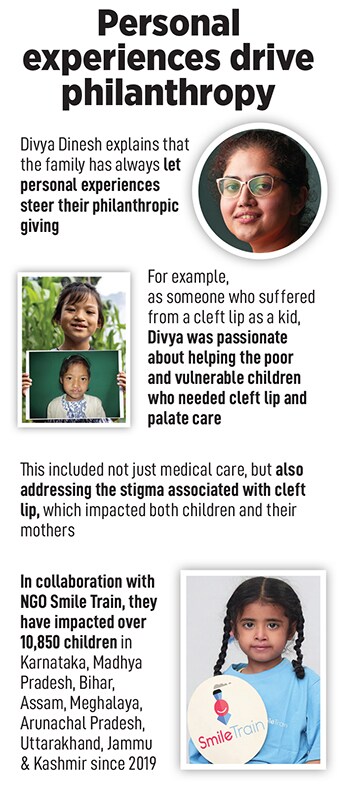

From health and education, livelihood, animal welfare, and environment and climate, and even disaster relief, K Dinesh's philanthropic endeavours span several causes and organisations to make a vast, lasting impact. A look at how his family—wife and two daughters—are the cornerstones of his philanthropic principles

(From left) Deeksha Dinesh, Asha Dinesh, K Dinesh and Divya Dinesh, channelise their philanthropy through the Ashraya Hastha Trust

Image:Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

(From left) Deeksha Dinesh, Asha Dinesh, K Dinesh and Divya Dinesh, channelise their philanthropy through the Ashraya Hastha Trust

Image:Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

K Dinesh loves telling stories. His face broadens with a smile as he narrates them. “That’s not the end of the story,” he says often, making room for an incoming twist in the tale.

One such anecdote is about how he got his first job in the software industry. He was applying for a programmer/analyst’s role in the public sector company, New Government Electrical Factory (NGEF). “Have you seen a computer?” the interviewer asked. Of course he had not seen one.

This was the early 70s, when there were just a few hundred computers in use in India. “I had never seen a computer, never used one, or even studied anything about it, but somehow computers fascinated me,” Dinesh says over a Zoom call in early January.

The interviewers wanted to know how Dinesh could program a computer if he had never seen one. “I know how to spell computer,” he had replied, making them laugh. “I told them that I don’t know anything, but I am keen to learn. With some training, they can help me do my job. And if I did not learn, only I will be the loser.”

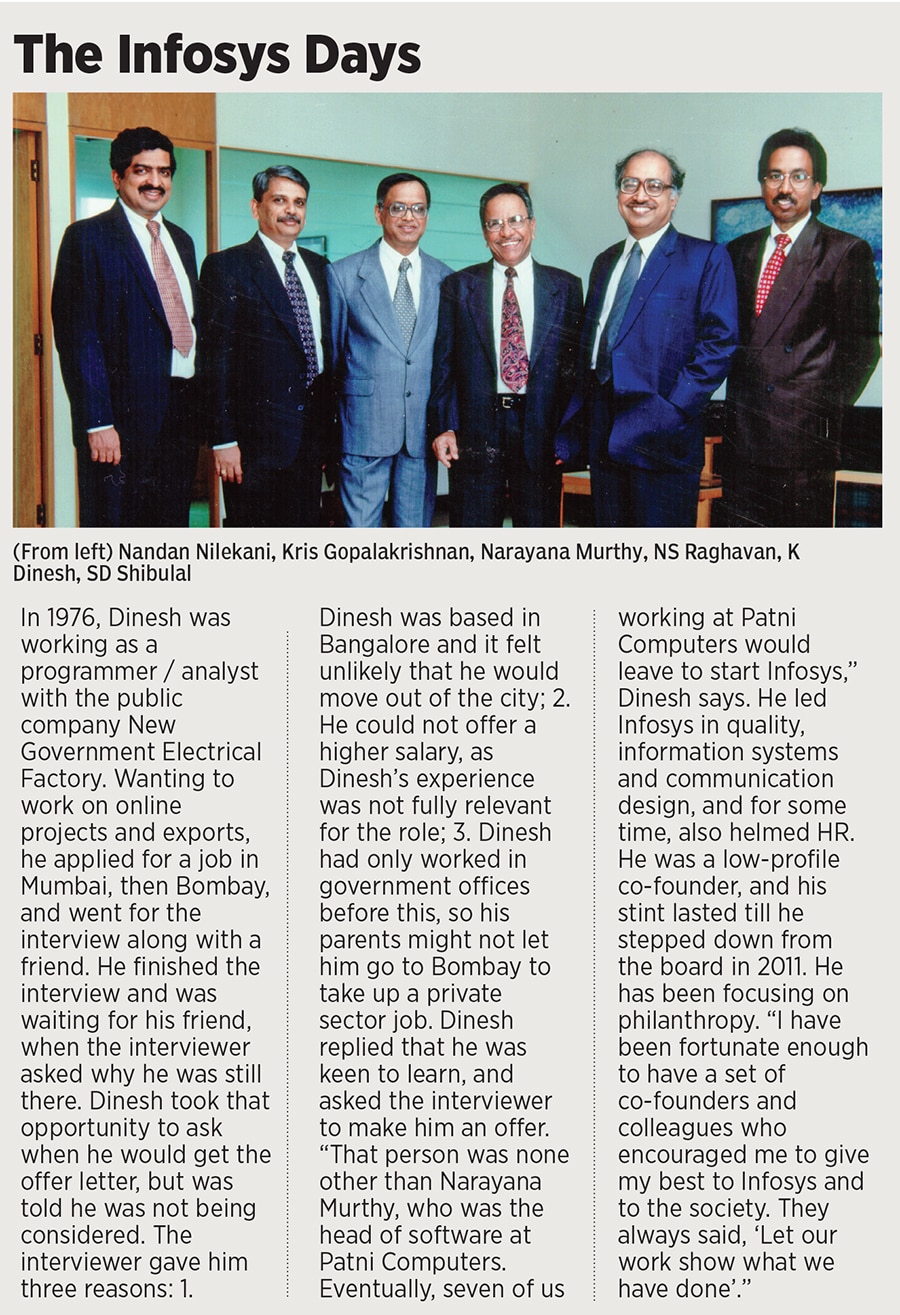

Dinesh refers to this willingness to learn at multiple points during our conversation, which stretches for over an hour. This penchant for learning new things and taking up challenges would go on to impress another interviewer, NR Narayana Murthy, about three years down the line in 1976.

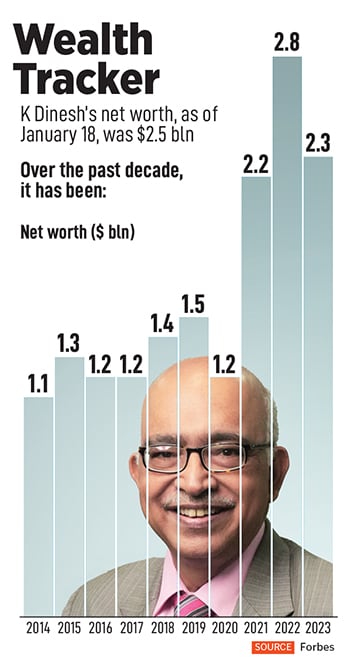

The billionaire status that Dinesh enjoys today as a result of Infosys—his net worth as of January 18 is $2.5 billion, according to Forbes—makes him feel like life before the 80s was a story from another lifetime. In 1971, he had obtained a BSc degree in Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics when he was just 17. In 1972, his first job as an RMS sorter in the Q Division of the Madras platform at the Bangalore City railway station paid him a stipend of ₹80 a month, and required him to sort letters as per then introduced PIN code throughout the night and in moving trains to Harihar. His second job was as a phone inspector with the telephones department, and his third was as a clerk with UCO Bank, before he landed at NGEF.

The billionaire status that Dinesh enjoys today as a result of Infosys—his net worth as of January 18 is $2.5 billion, according to Forbes—makes him feel like life before the 80s was a story from another lifetime. In 1971, he had obtained a BSc degree in Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics when he was just 17. In 1972, his first job as an RMS sorter in the Q Division of the Madras platform at the Bangalore City railway station paid him a stipend of ₹80 a month, and required him to sort letters as per then introduced PIN code throughout the night and in moving trains to Harihar. His second job was as a phone inspector with the telephones department, and his third was as a clerk with UCO Bank, before he landed at NGEF. Dinesh remembers how she used to cook a whole lot of food every day. “We used to ask why she is making so much food for just a few people at home. She used to say, ‘It won’t go waste, because my family also consists of my neighbours, the vegetable and milk vendor, and the person who will come to our doorstep begging for food’,” he recollects. His mother had only studied up to the seventh grade, but she taught him how people who are fortunate enough to have wealth should take care of those who don’t.

Dinesh remembers how she used to cook a whole lot of food every day. “We used to ask why she is making so much food for just a few people at home. She used to say, ‘It won’t go waste, because my family also consists of my neighbours, the vegetable and milk vendor, and the person who will come to our doorstep begging for food’,” he recollects. His mother had only studied up to the seventh grade, but she taught him how people who are fortunate enough to have wealth should take care of those who don’t.

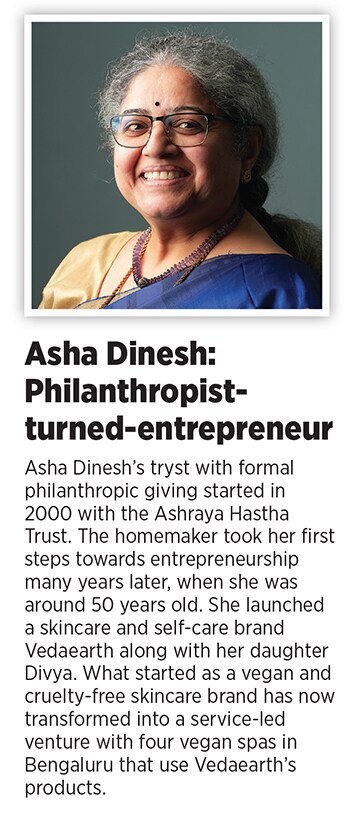

She adds that their initial steps into philanthropic giving was by observing the elders in their family, and watching how they went out of their way to help their neighbours or members of their community in the daily course of life. They also started with causes they could connect with. One of their initial projects, she explains, was helping public schools in villages, including Basarikatte and Neelakantanahalli in Karnataka. “These were mostly government schools that did not have the infrastructure, lacked a few classrooms, libraries or well-equipped labs. We got these schools equipped with whatever they needed,” Asha says.

She adds that their initial steps into philanthropic giving was by observing the elders in their family, and watching how they went out of their way to help their neighbours or members of their community in the daily course of life. They also started with causes they could connect with. One of their initial projects, she explains, was helping public schools in villages, including Basarikatte and Neelakantanahalli in Karnataka. “These were mostly government schools that did not have the infrastructure, lacked a few classrooms, libraries or well-equipped labs. We got these schools equipped with whatever they needed,” Asha says.