Uday Kotak: Going beyond the bank to shape India's financial sector

India's billionaire banker Uday Kotak, winner of the Forbes India Leadership Award for Institution Builder, shares mantras for new-age entrepreneurs to build a successful venture and sheds light on his new innings and plans to save the planet

Uday Kotak, Founder and Director, Kotak Mahindra Bank

Image: Mexy Xavier

Uday Kotak, Founder and Director, Kotak Mahindra Bank

Image: Mexy Xavier

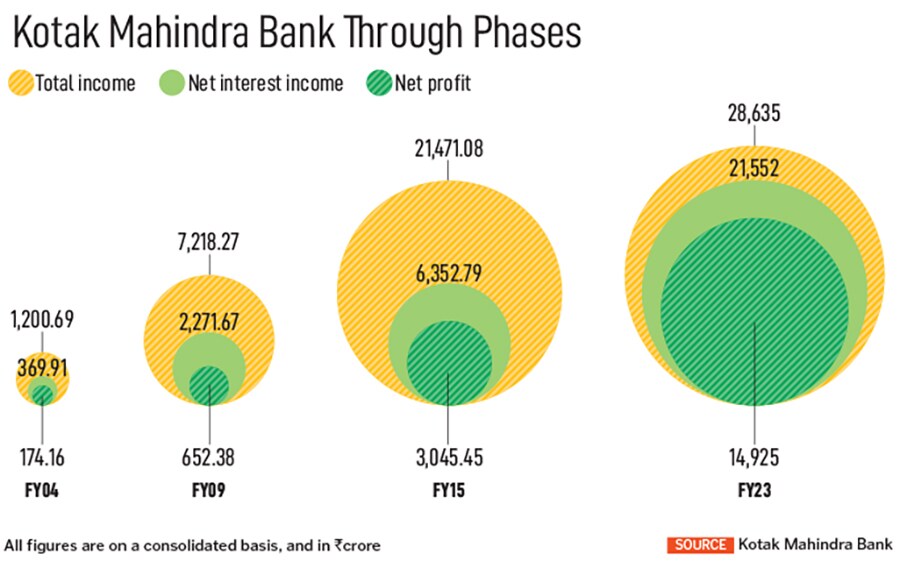

Uday Kotak sits at his family office, USK Capital, in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Complex, where construction activity continues in the landscape unabated. It is reflective of the fact that India’s celebrated billionaire banker—who successfully founded and built Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB), India’s fourth-largest bank by market capitalisation in just over two decades—has an “open” canvas in his new journey.

Kotak stepped down as the bank’s managing director and CEO on September 1, 2023, though he remains on its board as a director. He is now looking forward to wanting to add more towards building India’s financial sector through policy, and promoting talent and opportunities, he tells Forbes India.

Giving back for sustainability

Kotak, 64, is working on—as part of the B20 (the official G20 dialogue forum with the global business community)—creating a financial framework to help sustainability and lessen the existential risks to planet Earth. “The existential risk to the planet is much higher than the capability of the business models prevalent on Earth to save it,” Kotak says.If a project needed ₹100, the viability comes at ₹80 and ₹20 is the loss funding. Kotak has suggested using the backbone of India’s existing CSR model—every profitable company globally gives 0.2 percent of the 2 percent (CSR) of its annual profit, in the form of loss funding each year, towards social development goals to save the planet. The funds collected each year from all corporations could be given to a global institution such as the World Bank to leverage upon.

“If I know as a fund that I am going to get, for example, $100 billion each year, I can do bridge finance for the project right now. And this would solve Earth’s existential problem,” Kotak says.

Maruti got a huge float on which it earned an attractive 16 to 17 percent rate of interest, but KMFL, while gaining market share, took a hit on its profit and loss, as it was not charging a premium for immediate delivery of cars (as was the prevalent practice). “Whatever interest cost came out of the spread we were lending at,” Kotak says. “It is similar here [the B20 sustainability proposal], but in reverse.” Kotak is asking companies to “give back something” considering that every company benefits from the planet’s resources.

Maruti got a huge float on which it earned an attractive 16 to 17 percent rate of interest, but KMFL, while gaining market share, took a hit on its profit and loss, as it was not charging a premium for immediate delivery of cars (as was the prevalent practice). “Whatever interest cost came out of the spread we were lending at,” Kotak says. “It is similar here [the B20 sustainability proposal], but in reverse.” Kotak is asking companies to “give back something” considering that every company benefits from the planet’s resources. During the early days of the NBFC, individuals such as Shanti Ekambaram (now whole-time director and deputy MD from March 1, 2024), KVS Manian (now whole-time director and joint MD from March 1, 2024), Jaimin Bhatt (group chief financial officer), alongside others such as C Jayaram (former joint MD and now non-executive director) and Dipak Gupta (former joint MD) played larger roles as individuals, compared to the NBFC. Later when the NBFC converted to a full service bank, the institution became larger than the individuals.

During the early days of the NBFC, individuals such as Shanti Ekambaram (now whole-time director and deputy MD from March 1, 2024), KVS Manian (now whole-time director and joint MD from March 1, 2024), Jaimin Bhatt (group chief financial officer), alongside others such as C Jayaram (former joint MD and now non-executive director) and Dipak Gupta (former joint MD) played larger roles as individuals, compared to the NBFC. Later when the NBFC converted to a full service bank, the institution became larger than the individuals.