Denied trainee job at VIP, Tainwala now heads Samsonite International

Ramesh Tainwala's path to Samsonite International's CEO is rooted in both chance and choice. His ambitions, however, have their foundation in pure ability

Serendipity best describes the nearly two-decade-long journey Ramesh Dungarmal Tainwala, 55, has taken to become chief executive officer at Samsonite International, the world’s largest travel luggage maker.

Consider that in 1981, as a 22-year-old, Tainwala was rejected for a management trainee’s job with Indian luggage giant VIP Industries. Yet, a few years later, he became one of their long-time vendors, supplying the company with raw material and, later, plastic sheets.

Also consider that Tainwala might never have worked with Samsonite if not for a joint venture struck by chance. His elevation to the top post might not have happened either, given that Tainwala had resigned twice at Samsonite earlier.

Most of all, this: “[Prior to working with Samsonite] I had no clue how to make or sell luggage. The only luggage I used was what my wife got in her trousseau,” Tainwala, Samsonite’s CEO as of October 1, says in an interview with Forbes India. And now, Tainwala is shaping your luggage choices.

You have to call it serendipity.

In 1981, Tainwala, a postgraduate from the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS), Pilani, who grew up in Ranchi, in the eastern state of Jharkhand, applied for a management job at companies such as VIP Industries, Asian Paints and Century Spinning, among others.

These were reputed organisations and, equally importantly, based in Mumbai, the land of Bollywood, which Tainwala was enamoured with.

It was not to be. Not then, anyway. Tainwala got rejected by VIP as well as the others. But he didn’t lose heart. In 1983, he moved to Mumbai and started working with his uncle’s friend, Kamal Kumar Agarwal, who ran a polymers business and was a vendor to VIP, selling them plastic raw material. “I was excited about Mumbai and its glamour,” recounts Tainwala. A year later, he started out on his own as a small commodity trader, through a firm Tainwala Trading & Investments.

Tainwala says he managed to “stand out” as a commodity trader as he was interacting with people who were “sophisticated”. This was a combination of both “luck” and his “outgoing nature”, he says. He had come to know stalwarts like Idea Cellular’s former managing director Sanjeev Aga, who at that time worked with Blow Plast (which later merged with VIP). Tainwala’s other clients included Asian Paints, Kelvinator, Godrej and luggage firms Safari and the now-defunct Gujarat BD Luggage; some of these companies later started to buy raw material in the form of polymers from Tainwala when he started to sell later in 1984.

In 1985, as a natural progression of selling polymers, Tainwala decided to set up another company, Tainwala Chemicals, to manufacture plastic sheets which are moulded into making suitcases. The opportunity, as he saw it, was that some of his clients, who tried making these sheets themselves, were able to use only 20 percent of the capacity produced, a sub-optimal level for them.

To set up the company, Tainwala borrowed funds from family and friends to raise Rs 20 lakh. He also met some brokers who helped him successfully raise around Rs 50 lakh from the capital market (through an IPO) and the balance from banks (after successfully convincing ICICI’s then chairman Narayanan Vaghul): This resulted in a cumulative capital of Rs 2 crore in the late 1980s.

While still working on his own in the late 1980s, his main lender, ICICI (now ICICI Bank), approached him after Gujarat BD Luggage blamed Tainwala Chemicals as one of the factors for its non-revival, at a hearing with a government agency, Tainwala says. ICICI had been appointed as the nodal agency to revive the firm.

The charge, he points out, was that Tainwala Chemicals had not supplied Gujarat BD Luggage plastic sheets as it had not been paid dues for two years. “After a year-long hearing, ICICI asked me to take over Gujarat BD Luggage, which had a JV with American Tourister,” Tainwala says. (The Gujarat BD Luggage revival issue remained unresolved for a long time.)

Tainwala was evaluating this purchase option when he learnt that Samsonite had bought American Tourister in 1993. This prompted ICICI to ask Tainwala to initiate discussions with Samsonite on a potential buy-out of Gujarat BD Luggage, which had outstanding loans of about Rs 3 crore. “I thought if Samsonite takes over Gujarat BD Luggage, I might be able to recover my unpaid dues [Rs 20-30 lakh] and also hoped that Samsonite could become an additional customer to Tainwala Chemicals,” Tainwala says.

But the deal was never finalised. Samsonite had other ideas after India had opened up its economy to overseas investment, post the 1991 economic liberalisation. Samsonite, an established brand in the West, was keen to build its presence in India but, as per local rules, it required a local partner who would need to hold a 40 percent stake.

In 1994-95, Tainwala met Samsonite’s then president and CEO Luc Van Nevel. “Samsonite has the money, I need somebody reliable I can work with, Luc told me,” recounts Tainwala about the meeting with the Samsonite boss at Hotel Leela in Mumbai. “I told him, if you want me to work, I will.”

A few more years of negotiation resulted in the Tainwala Group and Samsonite entering into a 40-60 joint venture called Samsonite South Asia to manufacture international quality luggage in India. The JV continues with a professional board, while Tainwala now concentrates on Samsonite’s global operations.

Including the Samsonite JV, the Tainwala Group has a total turnover of Rs 1,500 crore, as of FY14. (Tainwala had started handing over control of all of his other businesses back to the family in 1994. The Tainwala Group has other ventures like Tainwala Personal Care (household insecticides, diapers), Abhishri Packaging (plastics and packaging products) and Abhishri Polycontainers (plastic containers).

“I live by the day so, as and when the opportunity comes, I take my chances. I do not hesitate,” Tainwala says. And when the opportunity arose in 1998, Tainwala was made managing director of the Indian region through the JV. But there were multiple challenges like poor telecommunications and distribution, when the manufacturing operations started, near Nashik. “The first two years were bad, with poor sales, and it was a difficult market,” says Tainwala.

Further, Samsonite usually entered a new market where the retail infrastructure—like departmental stores—existed. India had only mom-and-pop stores at that time, with very few departmental stores. Samsonite decided to create its own retail stores, in Mumbai and Dhanbad, Bihar, which were a success. “This was the turning point as, by the end of 2002, Samsonite had 150 stores across India, with a lot of them franchisees,” he says.

In 2004, India had become one of the fastest growing units in the Samsonite family. “The India experience established my credibility within Samsonite,” Tainwala says. Samsonite, learning from the India operations, adopted a similar approach of distribution—a mix of own retail stores and franchisees—in the Middle East and China. By 2011, Tainwala was handed charge of the entire Asia-Pacific region.

But Tainwala’s rise to the top still had its twists. He had resigned twice between 2004 and 2009. The first was in 2004-05, when Van Nevel—whom Tainwala considers his mentor—quit. Later, in 2009, Tainwala put in his papers when Van Nevel’s successor Marcello Bottoli, a former Louis Vuitton CEO, under whose leadership Tainwala strengthened Samsonite’s Middle East and Asia-Pacific businesses, left the company. Both times, Tainwala was asked to withdraw his resignation.

Post-2009 was Tainwala’s “most satisfying phase with Samsonite, working as part of Tim Parker’s leadership team”, he says. Tim Parker, whom Tainwala succeeds as CEO, has been credited with helping turn around several companies, including Clarks Shoes, Kwik-Fit, and also Samsonite.

In 2008-09, a division of Samsonite was aiming to file for bankruptcy as sales for its high-end luggage plunged due to slowing global consumer spends. Parker—known as the “Prince of Darkness” among trade unions for his job-cutting record—reduced costs and closed loss-making stores in Europe and the US. What also changed under Parker was that Samsonite became decentralised in its decision-making process.

“We don’t have a global head office. Decision-making is now undertaken by country heads. If you want to fight local players, you have to be as nimble or think locally as the smaller players do,” Tainwala says.

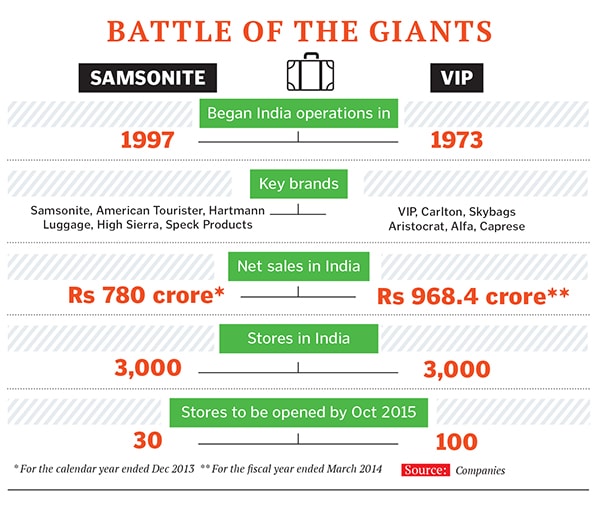

Though Samsonite has been in India for 17 years and is gaining market share from VIP, it is one of the few countries where it is yet to command complete leadership position. And this will be a tough task for Tainwala.

VIP, the country’s foremost luggage company since 1973, is also the largest, with a majority 52 percent market share in the organised luggage segment. Samsonite is second with a 37-38 percent market share and Safari a distant third with a near-seven percent share, according to analysts’ data.

These figures are disputed by Samsonite, which conducts different sales calculations under international accounting norms and says the Indian market is split half between itself and VIP.

In any case, the luggage sector in India is a high-entry barrier sector. Consider that luggage is a voluminous product, not bought casually or for everyday use. The retailer needs space, real estate costs are high and per square foot sales low. Also, dealers are known to get high incentives, in the range of 30-50 percent.

India is Samsonite’s fourth largest market, after US, China and Korea, where the unorganised, unbranded sector constitutes 65 percent and the organised sector the remaining 35 percent.

Samsonite has been growing in India at around 20-25 percent CAGR in the past five years. Its local sales touched Rs 780 crore in 2013 and the India business constituted six percent of Samsonite’s total global sales of $2.5 billion in 2013.

Currently, Samsonite has two main luggage brands. Its eponymous brand targets the high end of the market, with the price range starting at Rs 10,000, while American Tourister is in the mid-range, priced between Rs 3,500 to Rs 10,000. Rival VIP sells products, priced in the Rs 3,000 to Rs 7,000 range.

“Our business is built on taking careful steps and sometimes what you end up doing in a country is reflective of the competitive landscape. We have a choice: Either to get embroiled in a bloodbath or decide to do this much and no further,” says Tainwala. “Samsonite’s thinking is very clear: We want to engage in competition but not at the cost of profitability.” The new chief does not want his team to get “over-anxious” as long as it provides the consumer an exemplary product backed by efficient after-sales service.

“VIP is coming from an 80-90 percent market [which they once held]. A defensive competitor is much more aggressive, it will want to fight tooth-and-nail to maintain its leadership position,” he adds.

While Tainwala is unlikely to launch a blitzkrieg against VIP in a bid to try and win a 17-year-long India battle, he isn’t sitting idle either. Samsonite has a slew of new products, some just launched and others scheduled to hit India this quarter. Its most premium Black Label ‘Python’ collection was launched in October in India (priced Rs 34,200 onwards), where the sturdy luggage creates the look and feel of animal skin, but is actually not. Samsonite’s casual outdoor and sports brand High Sierra, which it acquired in 2012, will also be a frontrunner to boost India sales, with over 30 varieties in backpacks, rucksacks and travel luggage.

In 2012, Samsonite had launched a pilot ‘Project Pappu’, to woo the rural and mass market consumer with products priced at Rs 2,000-3,000, but it has not delivered enough for the firm. “Project Pappu was profitable, but was “way below” that of Samsonite’s core business,” says Tainwala. But he is confident that India, where business is doubling every three years, could touch Rs 2,000 crore in sales by 2017-18.

However, not if VIP has its way. The company, which started out as a hard luggage manufacturer, has diversified into making trolleys, backpacks, executive bags and also stylish handbags for women under the ‘Caprese’ brand. It has also been aligning processes with a new distribution structure. The company is now more focussed towards hypermarkets where its products sell faster compared to high street shops. Eighty percent of its sales are accounted for by soft luggage, all of which is manufactured in China. “We have to do more of the same to be on top—focus on innovation, product quality and be present in all segments,” Dilip Piramal, chairman of VIP Industries, tells Forbes India.

Piramal, who is “proud that a fellow Indian is heading Samsonite”, is even more satisfied that VIP still commands market leadership in India, despite Samsonite’s challenge. And analyst Manoj Bahety of Edelweiss Securities says VIP is not under threat to lose its leadership position in India as “both operate in almost different price segments”. “I have no idea about its international operations and management structure, but it [Samsonite] is a very strong brand, so unless it does something stupid, Tainwala should have a smooth run,” Piramal says.

Samsonite, globally, is a $2.5 billion company in sales and $380 million in profit. Tainwala hopes to grow it into a $5 billion company by sales and $1 billion in profit in five years. He plans to boost the South American business, where advertising at 2.5 percent of revenues is much lower than the average 6.5 percent for all main markets. (Samsonite spent $165 million overall on advertising in the last fiscal.) “Consumers, through advertising, can start to value one product over the other. I will not say no to anyone when one needs to spend more to build the brand,” Tainwala says.

These ambitions seem to have solid foundation in ability. For instance, his predecessor gives Tainwala the vote of confidence. “It was fairly obvious that he would eventually be my successor. He understands the business, is a good strategist, has great leadership skills but, most importantly, is a pragmatist,” Parker told Forbes India from London.

The evidence: At the end of a two-hour-long interview, Tainwala had pointed to all the Samsonite products displayed in his office. Most were part of the 2007 ‘Black Label’ collection, including a human torso (rib cage) design and a crocodile skin design, created in partnership with the late British fashion designer Alexander McQueen.

“I love these products. But they had bombed globally,” says Tainwala, “possibly since customers found them too costly at near $500 at that time. I keep these pieces as they remind me that everything does not work and that one is not invincible. If I fail, I, like Tim, do not analyse why. It is better to cut to the chase and move on.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)