Yogendra Yadav: India is a State-Nation, Not a Nation-State

India has created a new model to democratically deal with deep diversities. It accepts that political boundaries do not and need not coincide with cultural boundaries

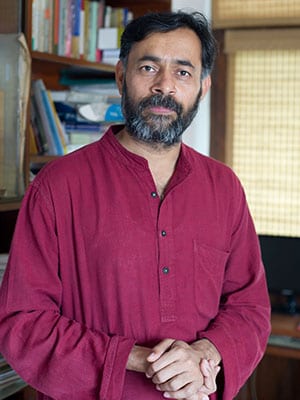

Yogendra Yadav

Profile: Yogendra Yadav is a senior fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Delhi. His interests include democratic theory, election studies, survey research. In 2009, the International Political Science Association awarded him the first Global South Solidarity Award.

The arrival of Narendra Modi at the centrestage of national politics has renewed an old debate about the idea of India. Underlying the various issues and controversies associated with Modi is a fundamental question: What kind of a nation are we? What does the Indianness of India consist of? How do we sustain a national political community across deep social and cultural diversities? Whose country is it anyway? This debate takes us back to the ghost of John Strachey, a British colonial administrator who wrote a primer in 1888 called India. The “first and the most essential thing to learn about India”, he advised his colonial masters, is that “there is not, and never was an India, or even any country of India, possessing, according to European ideas, any sort of unity, physical, political, social or religious…. That men of the Punjab, Bengal, the North Western Provinces, and Madras, should ever feel they belong to one great nation is impossible.”

This bald characterisation has continued to haunt Indians. It does so because Strachey was right in one sense. If nationhood requires people living within a given political boundary to have one language, one faith, one culture and one race, then claiming nationhood for India required stretching credulity. This is how the early nationalists responded to the colonial insinuation: They invoked the essential unity of the people of India, but struggled to explain how that essence fitted all the areas that fell within the boundaries of colonial India. The one thing they found hardest to wish away was religious diversity and divisions. The dilemma has persisted in post-colonial India.

It was natural for some Indian nationalists to try the other option. Instead of stretching the interpretation, they wanted to bend the reality itself by trying to forge a unity that would conform to received standards. This is how the politics of Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan was born. Guru Golwalkar, the iconic ideologue of the RSS, saw the challenge of nation building as requiring five unities: Geographical, racial, religious, cultural and linguistic. This project involved creating a uniform national community in the light of the cultural self-image of the dominant community. Thus their politics focussed on Hindi as the national language, Hindutva as the national way of life and the north Indian Hindi-speaking region as the heartland.

This vision of nationhood is more European than Indian. It draws upon a model of the nation-state that emerged in Europe. Europe’s civilisational unease with diversities has had a long history. Nineteenth century nation-states were an attempt to settle this unease by matching the cultural boundaries of a nation with the political boundaries of a state. If there was a mismatch, the nation-state model tried either to shift the political boundaries—by creating new countries or merging existing states—or to alter the cultural boundaries by means of cultural integration, assimilation, coercion and even ethnic cleansing.

Tableaux representing different states at the Republic Day parade. India’s cultural policy recognises and supports more than one cultural identity

This was, of course, not the vision shared by the mainstream of India’s national movement. If there was one thing Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru shared, it was their rejection of the idea that India’s unity requires uniformity. Although they continued to use the dominant expression ‘nation-state’ for their vision of India, they laid the foundation for a different approach that saw ‘unity in diversity’. The Indian Constitution and the post-independence politics has built an institutional edifice for recognition of diversity.

India’s ‘asymmetrical’ federalism recognises the unique situation of various states. The cultural policy of the state recognises and supports more than one cultural identity. The co-existence of Indian identity with other regional and religious identities is taken for granted. Political parties that raise regional and ethnic issues are not thrown out; they are brought within the pale of legitimate democratic negotiation of power. Quietly, but surely, India has created a new model of how to deal democratically with deep diversities. This model is best described as that of a ‘state-nation’. State-nation accepts that political boundaries do not and need not coincide with cultural boundaries and that a political community can be imagined across deep diversities.

India’s experience with diversities is not without its problems. The continuing alienation in Kashmir, and the ongoing slow-burning insurgencies in Nagaland and Manipur serve as a reminder of the failures of this experiment. But these are best seen as failures to implement the model of state-nation in its true spirit rather than the failures of this model itself. In any case, the disintegration of the former USSR and Yugoslavia serves to remind us that we cannot take our continued existence as a political unit for granted. The civil war in Sri Lanka and the slow disintegration of Pakistan serve as a reminder of what India could have faced if it followed the European-style nation-state.

It is time we turned to Narendra Modi and spoke through him to the spirit of John Strachey: Thank God, India is not Europe and we don’t live in the 19th century!

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)