Bimal Patel: We Have to Free Our Cities from the State's Clutches

The country’s creaking infrastructure has been unable to support its cities’ rapid growth. Local governments should be granted autonomy to increase productivity

Bimal Patel

Profile: Bimal Patel is Director, HCP Design and Project Management. Patel designed the Sabarmati Riverfront Development project in Ahmedabad.

India is witnessing an epochal transformation. From a country that lived in villages, it is becoming a nation of towns and cities. The last time the country witnessed such a transformation was during the period of the Mahabharata: Agricultural technology spread and village settlements transformed the subcontinent’s ecology, geography and economy. Today, scientific, technological and industrial improvements are propelling change. These changes are simultaneously making many rural livelihoods redundant, and turning cities into more productive and attractive places to work in. On account of this, a vast number of people are migrating from villages to cities.

Today, as a consequence of rapid growth, Indian cities are in a mess. They are overcrowded and their meagre infrastructure is highly stressed. They are polluted, unhygienic and often filthy. Roads are congested and traffic seems unmanageable. Social services and amenities are non-existent in most towns and local governments seem unable to cope. We seem to be descending into a downward spiral of urban ills, stagnating urban productivity and underdevelopment. Will we ever be able to make our cities efficient, livable and sustainable? Will we ever be able to make them abodes of happy and flourishing lives?

When asking such despondent questions, it serves well to remember that when the West first urbanised, its cities also fell apart. Nineteenth century London and Paris were also unmanageable messes—overcrowded, polluted, unhygienic, filthy, congested and hopeless. Engels’s and Dickens’s writings bring the miserable conditions of European slums and cities vividly to life.

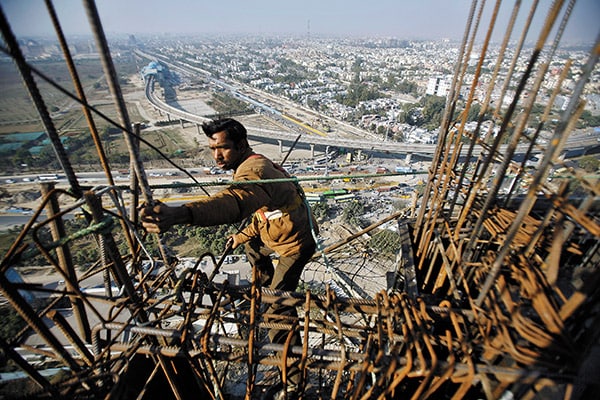

Image: Parivartan Sharma / Reuters

The task of developing our cities is primarily seen as the burden of state-level politicians

Slowly, over a century, Western nations were able to transform this situation. Starting from small beginnings, they were able to provide more and more people in cities with better infrastructure, transport, housing, schooling, health facilities and recreation. By doing this they were able to pull off the trick of simultaneously making city lives more comfortable, healthier and happier. This also made cities more productive. Basically, they were able to channel increased wealth, resulting from the increased productivity of cities, into urban infrastructure investment that improved the well being and productivity of more and more citizens. Successfully intertwining urbanisation and economic growth set off a virtuous upward spiral of human, social and economic development.

Why were Western nations able to transform their cities from the mess that they were in in the nineteenth century? Who provided the entrepreneurial leadership for this transformation? Why did this leadership respond to the plight of poor and deprived people in their cities? Why was the wealth generated by initial urbanisation not siphoned away by the elite or poorly invested—resulting in the falling productivity and worsening of living conditions in cities? Why did Western cities not get mired in a vicious downward spiral of unsustainable urbanisation and economic stagnation? These are difficult questions to answer unequivocally.

When one reads histories of urban development in the West it is clear that their cities were self-governing and autonomous. They were unfettered by higher levels of government. Local elites participated in governance and led the development of their cities. Local governments were expected to raise their own resources and had the powers to do so. They also had the powers to spend their resources in the manner that they saw fit. They had comprehensive control over their jurisdictions, including police powers. Local governments were responsible for all aspects of city life. Their staff was accountable to local government leaders. Moreover, local governments were effectively democratic. Local leaders were accountable to local populations. If they wanted to be re-elected, local politicians had to yield to the demands of their electorates and to seek their well-being.

Are Indian cities similarly autonomous? Are local governments effectively democratic?

We have all the trappings of autonomous and democratic local government—municipal corporations, municipalities, elected councilors, wards and so on. This creates a powerful illusion of self-governance at the local level. However, anyone who has interacted with local governments knows that our cities lack autonomy. They are creatures of state governments—created by state-level legislations and subservient to state-level politicians and administrators. In most places, mayors walk up to administrators’ offices and not the other way around. Councillors are not in charge of the machinery of local government and executives are not required to answer to them. Local politicians are not expected to forge a vision for their city, raise resources for development or decide where to spend money. On the contrary, all important plans and budgets have to be sanctioned at the state level. Of late, even the Central government has got into the act. Believing that it knows best what cities ought to be doing, it has set up various standard schemes for directly funding urban development. In our country, the task of developing our cities is primarily seen as the burden of state-level politicians and administrators. It is, therefore, no wonder that politicians worth their salt do not want to get involved in local government.

We also elect councillors to our local governments. This also creates a powerful illusion that we have democratic local self-governance. Our councillors represent the people only in the sense that they are mediators, ‘liaison agents’ if you will, for the population to deal with the machinery of local government. If one observes them at work, it is clear that their primary task is to help their constituents, rich and poor alike, to negotiate the Kafkaesque maze of local government. They help in accessing local government officials, making sense of complicated and often contradictory regulations, obtaining dispensations and resolving problems that people have got themselves into, most often, unwittingly and inadvertently.

Local politicians in India help to solve the problems of individual petitioners. They do not represent those who elect them as a class. As a consequence of this, for most civic politicians, a stint in local government is not more than a short opportunity to indulge in petty corruption. If this is not true, there is no way of explaining why despite the fact that the poor are in a majority and we have elected representatives, the problems of poor people are simply not addressed.

A nation urbanises only once. Today we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to use urbanisation to set off a virtuous spiral of social and economic development in India. To do this we have to make sure that our cities rapidly become more and comfortable, healthier and happier places for all the people who live in them. Only then will we be able to continually increase their productivity and reap the benefits of economic growth.

The most effective way of ensuring that the wealth generated by cites is used to meaningfully transform our cities is to make local governments more autonomous and responsible for themselves, and to ensure that they are made more accountable to the people whom they govern.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)