Being humane: How business scions are furthering the legacy of giving

An emerging generation of donors, driven by strategy and impact, is altering the nature of philanthropy

Images (Clockwise): Arun Chittilappilly: Nishant Rantnakar for Forbes India; Rohan Murty & Deval Sanghavi: Joshua Navalkar; Rajvi Mariwala: Aditi Tailang; Janhavi Nilekani: Nishant Rantnakar for Forbes India; Aparna Piramal Raje, Trishya Screwvala & Parth Jindal: Aditi Tailang; Adar Poonawalla: Vikas Khot

Images (Clockwise): Arun Chittilappilly: Nishant Rantnakar for Forbes India; Rohan Murty & Deval Sanghavi: Joshua Navalkar; Rajvi Mariwala: Aditi Tailang; Janhavi Nilekani: Nishant Rantnakar for Forbes India; Aparna Piramal Raje, Trishya Screwvala & Parth Jindal: Aditi Tailang; Adar Poonawalla: Vikas KhotUntil recently it was depressingly common to see children in Palghar with potbellies and legs like twigs. Just 115 km from Mumbai, the forested, predominantly tribal, district suffered from a child malnutrition rate of 54 percent in 2014. That’s when the JSW Foundation, headed by Sangita Jindal, stepped in to help.

Her son Parth Jindal, who runs the conglomerate’s cement business, however, had a different plan. He was quick to note that data had to be central to their intervention efforts. Despite spending heavily on health and food-relief programmes in the area, the government authorities were only making a dent in the problem. Partly because the information they were gathering—in physical registers—was inaccurate. “There were huge gaps in the data they were collecting and what we were seeing on ground,” says Jindal.

Her son Parth Jindal, who runs the conglomerate’s cement business, however, had a different plan. He was quick to note that data had to be central to their intervention efforts. Despite spending heavily on health and food-relief programmes in the area, the government authorities were only making a dent in the problem. Partly because the information they were gathering—in physical registers—was inaccurate. “There were huge gaps in the data they were collecting and what we were seeing on ground,” says Jindal. Under his direction, the foundation developed an Android-based app to monitor the development indicators of children under the age of six. Local women, nicknamed ‘Yashodas’, were trained to take photographs of mother and child on their mobile phones, iris-scan them and enter the required information in the app. Today, this allows for real-time, GPS-enabled tracking of the nutrition and growth markers of children, letting doctors and officials take follow-up action where needed. Malnutrition, as a result, has fallen by 92 percent in the three talukas of Palghar that the JSW Foundation works in, claims Jindal. So measurable is the change that Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis has mandated that the technology be rolled out across Maharashtra.

All of 28, Jindal is one of the next-generation philanthropists who stand to inherit millions—if not billions—in private wealth, as also a legacy of giving. Eager to take forward their family’s tradition of philanthropy, and happily acknowledging the influence of their parents or grandparents in shaping their idea of giving, this younger lot is driven by strategy and impact rather than recognition or obligation, as was often the case earlier. But while the terms ‘impact-driven’ philanthropy, ‘strategic’ philanthropy or ‘venture-based’ philanthropy are bandied about, how different are these emerging donors compared to their older counterparts and, importantly, how effective is their approach?

All of 28, Jindal is one of the next-generation philanthropists who stand to inherit millions—if not billions—in private wealth, as also a legacy of giving. Eager to take forward their family’s tradition of philanthropy, and happily acknowledging the influence of their parents or grandparents in shaping their idea of giving, this younger lot is driven by strategy and impact rather than recognition or obligation, as was often the case earlier. But while the terms ‘impact-driven’ philanthropy, ‘strategic’ philanthropy or ‘venture-based’ philanthropy are bandied about, how different are these emerging donors compared to their older counterparts and, importantly, how effective is their approach? *****

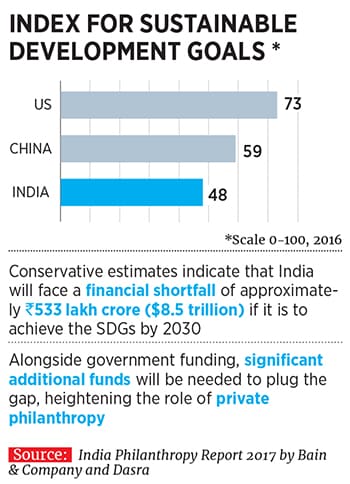

India is in the midst of one of the largest wealth transfers in history,” says Deval Sanghavi, partner and co-founder at Dasra, an organisation that helps donors better strategise their philanthropy. Some ₹12,800 crore, or $128 billion, will be transferred from one generation to the next in the coming decade, he says, citing research by Karvy Private Wealth.

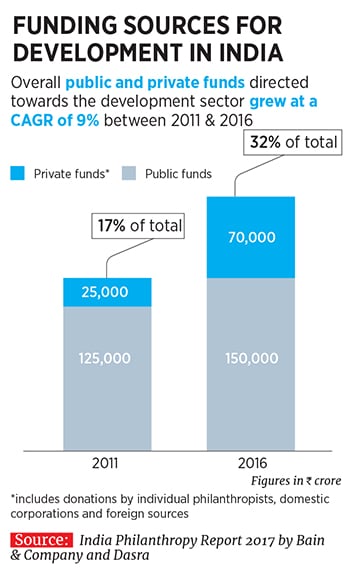

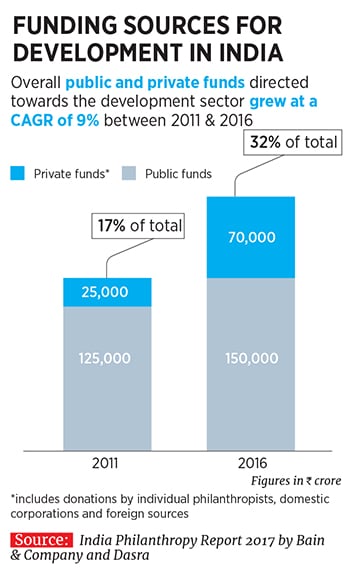

Much of this wealth has already been directed towards philanthropy. Private donations accounted for 32 percent of the total contributions to the development sector in 2016, up from 17 percent in 2011, according to consultancy Bain.

It’s a trend that will only grow stronger, as the younger generation to whom wealth is being transferred—along with responsibility and decision-making powers—is “socially conscious”, says Sanghavi. They’re informed, aware and want to make a difference to the world’s knottiest problems. “It’s built in their DNA.”

And so they’re taking to philanthropy at an early age. “I don’t need to wait till I’m 60 to start giving. I’ve been given a good life, so why not start now?” shrugs Adar Poonawalla. Son of billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, who founded India’s foremost vaccine-maker Serum Institute of India, the 37-year-old set up an eponymous clean-city initiative in 2015 to improve waste-management in his hometown Pune. “I would be embarrassed when foreign business partners visited us,” he says. “Besides, the garbage and filth is damaging our health and environment. So, instead of criticising the government, I decided to take matters in my hands.” He pledged ₹100 crore to the cause and set up a separate entity that undertakes waste-management along 400 km of roads in Pune, or roughly half the city.

And so they’re taking to philanthropy at an early age. “I don’t need to wait till I’m 60 to start giving. I’ve been given a good life, so why not start now?” shrugs Adar Poonawalla. Son of billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, who founded India’s foremost vaccine-maker Serum Institute of India, the 37-year-old set up an eponymous clean-city initiative in 2015 to improve waste-management in his hometown Pune. “I would be embarrassed when foreign business partners visited us,” he says. “Besides, the garbage and filth is damaging our health and environment. So, instead of criticising the government, I decided to take matters in my hands.” He pledged ₹100 crore to the cause and set up a separate entity that undertakes waste-management along 400 km of roads in Pune, or roughly half the city.

So, rather than merely provide top-down medical help, MHI advocates working with communities to also provide social safety nets like referrals for vocational training, for instance. “The cost to treat per person can vary from ₹200 to as high as ₹20,000 and I had a hard time convincing my dad about it,” says Mariwala. But he eventually came around, given the dire need for quality interventions. Today, MHI actively engages in thought leadership by publishing journals to change the discourse around mental health, and is also developing toolkits to help would-be funders assess impact.

So, rather than merely provide top-down medical help, MHI advocates working with communities to also provide social safety nets like referrals for vocational training, for instance. “The cost to treat per person can vary from ₹200 to as high as ₹20,000 and I had a hard time convincing my dad about it,” says Mariwala. But he eventually came around, given the dire need for quality interventions. Today, MHI actively engages in thought leadership by publishing journals to change the discourse around mental health, and is also developing toolkits to help would-be funders assess impact.

While the ‘what’ of the next-generation’s idea of philanthropy differs, the ‘why’ of their philanthropy is not so different from that of their predecessors. Hard facts and numbers matter, but not as much as the little differences they’re able to make. “When you see a student’s eyes light up after getting admission in his dream college, or you notice how her confidence has been upped because of a little mentoring, it makes everything worth it,” smiles Screwvala.

Jindal echoes a similar sentiment as he recalls a conversation he had with Thangjam Tababi Devi’s parents, after she won Silver at the Youth Olympic Games in Argentina. A judoka, Tababi is a product of JSW’s Sports Excellence Program, now housed under the Inspire Institute of Sports, that Jindal set up to improve India’s depressing shows at international sporting events. Her father, a rag picker from a remote village in Manipur, and her fish vendor mother were overjoyed, says Jindal. “We wanted to give them something, so I asked them what they would like…” His voice trails and eyes well up, “All they asked for was a year-long supply of rice.”

Jindal echoes a similar sentiment as he recalls a conversation he had with Thangjam Tababi Devi’s parents, after she won Silver at the Youth Olympic Games in Argentina. A judoka, Tababi is a product of JSW’s Sports Excellence Program, now housed under the Inspire Institute of Sports, that Jindal set up to improve India’s depressing shows at international sporting events. Her father, a rag picker from a remote village in Manipur, and her fish vendor mother were overjoyed, says Jindal. “We wanted to give them something, so I asked them what they would like…” His voice trails and eyes well up, “All they asked for was a year-long supply of rice.”

*****

When Jeff Bezos announced that he would give $2 billion of his fortune to tackle homelessness and improve pre-school education in the US, he drew parallels with his ecommerce business. “We’ll use the same set of principles that have driven Amazon… most important among those will be genuine, intense customer obsession,” he said in a statement in September. “The child will be the customer.”

But the idea of applying entrepreneurial chops to solve social problems is hardly new. Andrew Carnegie presented the idea back in 1889 in an essay titled ‘The Gospel of Wealth’. He wrote that “surplus revenues” amassed by the super-rich should be looked upon as “trust funds”.

“The man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer—doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves,” noted the industrialist who is estimated to have parted with 90 percent of his wealth to build schools, establish libraries and fund scientific research, by the time he died in 1919.

Closer home, Serum Institute’s Poonawalla, JSW’s Jindal, and even Arun Chittilappilly of V-Guard and Wonderla, talk of efficiency and scalability of their philanthropic endeavours, just as easily as they talk of business. “We found that international charities tend to have high overheads. So instead of giving to them we prefer to carry out our foundation work directly where we can keep checks and balances in place, just like one would in business. It ensures that money goes to those who need it the most and increases the effectiveness of our work,” says Chittilappilly, referring to the education and health care-focussed charity set up by his father Kochouseph Chittilappilly, who marked his 60th birthday some years ago by donating one of his kidneys to an ailing truck driver unknown to him.

Closer home, Serum Institute’s Poonawalla, JSW’s Jindal, and even Arun Chittilappilly of V-Guard and Wonderla, talk of efficiency and scalability of their philanthropic endeavours, just as easily as they talk of business. “We found that international charities tend to have high overheads. So instead of giving to them we prefer to carry out our foundation work directly where we can keep checks and balances in place, just like one would in business. It ensures that money goes to those who need it the most and increases the effectiveness of our work,” says Chittilappilly, referring to the education and health care-focussed charity set up by his father Kochouseph Chittilappilly, who marked his 60th birthday some years ago by donating one of his kidneys to an ailing truck driver unknown to him.

However, Screwvala sounds caution. Applying the rigour of a business to a not-for-profit is good, she says, but “scale” for example, is not the core objective of the Lighthouse Project. “My father for instance, is ocused on scale; Swades [Ronnie and Zarina Screwvala’s foundation that helps lift rural Indians out of poverty] has done tremendous work across large geographies in rural Maharastra. However, we have chosen to focus more on the depth and personal equation of each relationship, since mentoring is a long term process that involves changing mindsets and behavioural patterns.”

*****

Wedged between local stores, dumpsters and crushing traffic lies the entrance to Jijamata Nagar, a sprawling slum in Mumbai’s Worli. Shacks, often little more than blue tarpaulin sheets strung over metal struts, flank the alleyways that lead up to Shabina Khan’s doorstep.

A slight 26-year-old, she parts the floral blue curtain that acts as a door to her home and flashes a smile. “mMitra has really helped me,” she says in Hindi, holding her toddler on her hip while her two older children frolic about. “From the time I was three months pregnant with this one,” she says, lurching her baby forward, “I’ve been listening to their calls and following their advice. I wasn’t able to for my first two children and you can see the difference. This one is more active and has stronger immunity.”

A free mobile voice call service, mMitra provides information on preventive care to pregnant and lactating women. After registering their mobile numbers with Armman, the NGO behind the service, they can choose the time of the day they’d like to receive the bi-weekly calls. Today, mMitra serves 20 lakh women, mostly in Maharashtra, but also in Karnataka, Gujarat and Rajasthan.

A free mobile voice call service, mMitra provides information on preventive care to pregnant and lactating women. After registering their mobile numbers with Armman, the NGO behind the service, they can choose the time of the day they’d like to receive the bi-weekly calls. Today, mMitra serves 20 lakh women, mostly in Maharashtra, but also in Karnataka, Gujarat and Rajasthan.

“I was looking for ways to help out and was sector agnostic,” says Aparna Piramal Raje, 42, “when the folks at Dasra introduced me to Armman.” Daughter of VIP Industries’ Chairman Dilip Piramal and business historian Gita Piramal, Raje did her homework, met with Dr Aparna Hegde, the NGO’s founder, and spoke with experts in the field, all through Dasra.

It is here—in the ‘how’—that today’s philanthropists mark a clear departure from the past. Younger philanthropists readily engage in partnerships—with their peers, service providers or organisations like Dasra—to amplify their work. In Raje’s case, once she was convinced about Armman, she decided to enter one of Dasra’s “giving circles”—a grouping of 10 philanthropists who donate ₹10 lakh annually for a period of three years and collectively decide on disbursements to an NGO. She drummed up support from her network of neighbours and formed her own consortium, a subset of a circle, in 2017. Today their monies are spent not just to scale up the mMitra call service, but also to build and strengthen capacity at Armman.

“Often we see that because of the increased focus on ‘impact’ and ‘numbers’, donors only want to support a programme, but not the NGO. But if the NGO doesn’t have the right infrastructure in place, how will the programme go on? It takes an enlightened donor to understand this,” says Noshir Dadrawala, CEO at the Centre for Advancement of Philanthropy, a Mumbai-based organisation that specialises in charity law and good governance practices for non-profits. Menon of the Gates Foundation concurs. While a new wave of giving is taking over, “philanthropy needs to invest in the future of philanthropy”, he says. “We need tens of hundreds of Dasras, Ashoka Universities and other such organisations.”

“Often we see that because of the increased focus on ‘impact’ and ‘numbers’, donors only want to support a programme, but not the NGO. But if the NGO doesn’t have the right infrastructure in place, how will the programme go on? It takes an enlightened donor to understand this,” says Noshir Dadrawala, CEO at the Centre for Advancement of Philanthropy, a Mumbai-based organisation that specialises in charity law and good governance practices for non-profits. Menon of the Gates Foundation concurs. While a new wave of giving is taking over, “philanthropy needs to invest in the future of philanthropy”, he says. “We need tens of hundreds of Dasras, Ashoka Universities and other such organisations.”

Meanwhile, newer avenues like impact investing are opening up. A form of investing that seeks to generate both a social benefit as well as a meaningful financial return, it is still “a nascent area”, says Yatin Shah, co-founder and executive director at IIFL Investment Managers. “But it will grow in time to come. Our clients’ children are asking questions and exploring ways to give effectively and meaningfully,” he adds.

As the philanthropic landscape evolves, one constant remains: “For all the talk about giving, I actually get so much back in terms of intellectual stimulation, learning, fulfilment and pure joy,” says Raje.

That’s a benefit that can’t be measured.

It’s a trend that will only grow stronger, as the younger generation to whom wealth is being transferred—along with responsibility and decision-making powers—is “socially conscious”, says Sanghavi. They’re informed, aware and want to make a difference to the world’s knottiest problems. “It’s built in their DNA.”

And so they’re taking to philanthropy at an early age. “I don’t need to wait till I’m 60 to start giving. I’ve been given a good life, so why not start now?” shrugs Adar Poonawalla. Son of billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, who founded India’s foremost vaccine-maker Serum Institute of India, the 37-year-old set up an eponymous clean-city initiative in 2015 to improve waste-management in his hometown Pune. “I would be embarrassed when foreign business partners visited us,” he says. “Besides, the garbage and filth is damaging our health and environment. So, instead of criticising the government, I decided to take matters in my hands.” He pledged ₹100 crore to the cause and set up a separate entity that undertakes waste-management along 400 km of roads in Pune, or roughly half the city.

And so they’re taking to philanthropy at an early age. “I don’t need to wait till I’m 60 to start giving. I’ve been given a good life, so why not start now?” shrugs Adar Poonawalla. Son of billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, who founded India’s foremost vaccine-maker Serum Institute of India, the 37-year-old set up an eponymous clean-city initiative in 2015 to improve waste-management in his hometown Pune. “I would be embarrassed when foreign business partners visited us,” he says. “Besides, the garbage and filth is damaging our health and environment. So, instead of criticising the government, I decided to take matters in my hands.” He pledged ₹100 crore to the cause and set up a separate entity that undertakes waste-management along 400 km of roads in Pune, or roughly half the city. Not just is the next-gen taking to philanthropy at a younger age, it is often engaging in it full time. Take the case of Trishya Screwvala, daughter of media mogul Ronnie Screwvala, who, while dabbling in film production, found that “structured opportunities” to volunteer didn’t quite exist in India. “It was all ad hoc,” says the 32-year-old. While those running NGOs would rue volunteers’ lack of commitment, those eager to volunteer would tell her that seeking out the right opportunities was a challenge. “There was a clear demand-supply gap,” says Screwvala.

To plug that gap she set up The Lighthouse Project, a not-for-profit that pairs volunteers with children from under-resourced communities aged 13 and above, to mentor, guide and shape their futures. “Going from education to employment is often a challenge if you don’t have the right guidance,” says Screwvala. “We’re hoping to change that.” Since starting out in 2013, the Mumbai-based organisation boasts 700 mentors and 700 mentees who meet twice every month over one academic year.

Ditto with Infosys Co-founder Nandan Nilekani’s daughter Janhavi Nilekani, 30. After graduating in economics and development from Yale University and following it up with a PhD in public policy from Harvard University, she is now in the midst of setting up a “philanthropy research lab” that will pull together her academic learnings, as well as the lessons she’s imbibed from her philanthropist parents, to improve maternal health care in India. “Since my senior year at Yale, I knew I wanted to work in the development sector,” she says.

Ditto with Infosys Co-founder Nandan Nilekani’s daughter Janhavi Nilekani, 30. After graduating in economics and development from Yale University and following it up with a PhD in public policy from Harvard University, she is now in the midst of setting up a “philanthropy research lab” that will pull together her academic learnings, as well as the lessons she’s imbibed from her philanthropist parents, to improve maternal health care in India. “Since my senior year at Yale, I knew I wanted to work in the development sector,” she says.

“It’s not just about cheque-writing for them [next-gen philanthropists],” notes Hari Menon, director at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, where he oversees global philanthropy strategy, particularly focusing on India and the Middle East. “They’re eager to roll up their sleeves and devote their time, talent and expertise to the causes they care about.”

Philanthropy of the past was often directed towards religion, or communities and institutions. Building temples, hospitals or schools was commonplace, notes Dasra’s Sanghavi. “That was needed at the time. But now that the government provides much of these services, the focus has shifted from providing the hardware to looking at the software,” he adds. So instead of just building toilets, newer philanthropists also worry about changing behaviours so that people actually use them. Or rather than just setting up a school, they’re also looking at education outcomes.

Philanthropy of the past was often directed towards religion, or communities and institutions. Building temples, hospitals or schools was commonplace, notes Dasra’s Sanghavi. “That was needed at the time. But now that the government provides much of these services, the focus has shifted from providing the hardware to looking at the software,” he adds. So instead of just building toilets, newer philanthropists also worry about changing behaviours so that people actually use them. Or rather than just setting up a school, they’re also looking at education outcomes.

The focus is more long-term, more systemic and more nuanced. Consider the Murty Classical Library of India at Harvard University that alumnus Rohan Murty set up in 2010 with a $5.2 million bequest. “My father [Infosys Founder Narayana Murthy] and I would often debate… he’s interested in solving problems that are relevant today and for the future—creating jobs, education, etc. But I look at longer-term horizons and also what we can learn from the past for a better future,” says the 35-year-old. “I’m interested in systems that produce and sustain knowledge and make it accessible and mainstream. Look at the history of mankind,” he argues, “Buildings and monuments fall away, powerful people come and go, but what has withstood the sands of time is knowledge. It influences mankind’s thought.”

So also with Marico Founder Harsh Mariwala’s daughter Rajvi Mariwala, 38. A canine behaviourist, she set up the Mariwala Health Initiative (MHI) in 2015 to provide funding and capacity-building support to NGOs working in the area of mental health. “It’s an area that has been neglected for too long because of the stigma around it,” she says. But the sheer numbers of those silently suffering from mental illnesses—150 million Indians were in need of active interventions, according to the 2016 National Mental Health Survey—as well as conversations with service providers, beneficiaries and experts in the field, convinced her of the need for a “rights-based approach” to mental health. To plug that gap she set up The Lighthouse Project, a not-for-profit that pairs volunteers with children from under-resourced communities aged 13 and above, to mentor, guide and shape their futures. “Going from education to employment is often a challenge if you don’t have the right guidance,” says Screwvala. “We’re hoping to change that.” Since starting out in 2013, the Mumbai-based organisation boasts 700 mentors and 700 mentees who meet twice every month over one academic year.

Ditto with Infosys Co-founder Nandan Nilekani’s daughter Janhavi Nilekani, 30. After graduating in economics and development from Yale University and following it up with a PhD in public policy from Harvard University, she is now in the midst of setting up a “philanthropy research lab” that will pull together her academic learnings, as well as the lessons she’s imbibed from her philanthropist parents, to improve maternal health care in India. “Since my senior year at Yale, I knew I wanted to work in the development sector,” she says.

Ditto with Infosys Co-founder Nandan Nilekani’s daughter Janhavi Nilekani, 30. After graduating in economics and development from Yale University and following it up with a PhD in public policy from Harvard University, she is now in the midst of setting up a “philanthropy research lab” that will pull together her academic learnings, as well as the lessons she’s imbibed from her philanthropist parents, to improve maternal health care in India. “Since my senior year at Yale, I knew I wanted to work in the development sector,” she says. “It’s not just about cheque-writing for them [next-gen philanthropists],” notes Hari Menon, director at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, where he oversees global philanthropy strategy, particularly focusing on India and the Middle East. “They’re eager to roll up their sleeves and devote their time, talent and expertise to the causes they care about.”

*****

Philanthropy of the past was often directed towards religion, or communities and institutions. Building temples, hospitals or schools was commonplace, notes Dasra’s Sanghavi. “That was needed at the time. But now that the government provides much of these services, the focus has shifted from providing the hardware to looking at the software,” he adds. So instead of just building toilets, newer philanthropists also worry about changing behaviours so that people actually use them. Or rather than just setting up a school, they’re also looking at education outcomes.

Philanthropy of the past was often directed towards religion, or communities and institutions. Building temples, hospitals or schools was commonplace, notes Dasra’s Sanghavi. “That was needed at the time. But now that the government provides much of these services, the focus has shifted from providing the hardware to looking at the software,” he adds. So instead of just building toilets, newer philanthropists also worry about changing behaviours so that people actually use them. Or rather than just setting up a school, they’re also looking at education outcomes.The focus is more long-term, more systemic and more nuanced. Consider the Murty Classical Library of India at Harvard University that alumnus Rohan Murty set up in 2010 with a $5.2 million bequest. “My father [Infosys Founder Narayana Murthy] and I would often debate… he’s interested in solving problems that are relevant today and for the future—creating jobs, education, etc. But I look at longer-term horizons and also what we can learn from the past for a better future,” says the 35-year-old. “I’m interested in systems that produce and sustain knowledge and make it accessible and mainstream. Look at the history of mankind,” he argues, “Buildings and monuments fall away, powerful people come and go, but what has withstood the sands of time is knowledge. It influences mankind’s thought.”

While the ‘what’ of the next-generation’s idea of philanthropy differs, the ‘why’ of their philanthropy is not so different from that of their predecessors. Hard facts and numbers matter, but not as much as the little differences they’re able to make. “When you see a student’s eyes light up after getting admission in his dream college, or you notice how her confidence has been upped because of a little mentoring, it makes everything worth it,” smiles Screwvala.

*****

When Jeff Bezos announced that he would give $2 billion of his fortune to tackle homelessness and improve pre-school education in the US, he drew parallels with his ecommerce business. “We’ll use the same set of principles that have driven Amazon… most important among those will be genuine, intense customer obsession,” he said in a statement in September. “The child will be the customer.”

But the idea of applying entrepreneurial chops to solve social problems is hardly new. Andrew Carnegie presented the idea back in 1889 in an essay titled ‘The Gospel of Wealth’. He wrote that “surplus revenues” amassed by the super-rich should be looked upon as “trust funds”.

“The man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer—doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves,” noted the industrialist who is estimated to have parted with 90 percent of his wealth to build schools, establish libraries and fund scientific research, by the time he died in 1919.

Closer home, Serum Institute’s Poonawalla, JSW’s Jindal, and even Arun Chittilappilly of V-Guard and Wonderla, talk of efficiency and scalability of their philanthropic endeavours, just as easily as they talk of business. “We found that international charities tend to have high overheads. So instead of giving to them we prefer to carry out our foundation work directly where we can keep checks and balances in place, just like one would in business. It ensures that money goes to those who need it the most and increases the effectiveness of our work,” says Chittilappilly, referring to the education and health care-focussed charity set up by his father Kochouseph Chittilappilly, who marked his 60th birthday some years ago by donating one of his kidneys to an ailing truck driver unknown to him.

Closer home, Serum Institute’s Poonawalla, JSW’s Jindal, and even Arun Chittilappilly of V-Guard and Wonderla, talk of efficiency and scalability of their philanthropic endeavours, just as easily as they talk of business. “We found that international charities tend to have high overheads. So instead of giving to them we prefer to carry out our foundation work directly where we can keep checks and balances in place, just like one would in business. It ensures that money goes to those who need it the most and increases the effectiveness of our work,” says Chittilappilly, referring to the education and health care-focussed charity set up by his father Kochouseph Chittilappilly, who marked his 60th birthday some years ago by donating one of his kidneys to an ailing truck driver unknown to him. However, Screwvala sounds caution. Applying the rigour of a business to a not-for-profit is good, she says, but “scale” for example, is not the core objective of the Lighthouse Project. “My father for instance, is ocused on scale; Swades [Ronnie and Zarina Screwvala’s foundation that helps lift rural Indians out of poverty] has done tremendous work across large geographies in rural Maharastra. However, we have chosen to focus more on the depth and personal equation of each relationship, since mentoring is a long term process that involves changing mindsets and behavioural patterns.”

*****

Wedged between local stores, dumpsters and crushing traffic lies the entrance to Jijamata Nagar, a sprawling slum in Mumbai’s Worli. Shacks, often little more than blue tarpaulin sheets strung over metal struts, flank the alleyways that lead up to Shabina Khan’s doorstep.

A slight 26-year-old, she parts the floral blue curtain that acts as a door to her home and flashes a smile. “mMitra has really helped me,” she says in Hindi, holding her toddler on her hip while her two older children frolic about. “From the time I was three months pregnant with this one,” she says, lurching her baby forward, “I’ve been listening to their calls and following their advice. I wasn’t able to for my first two children and you can see the difference. This one is more active and has stronger immunity.”

“I was looking for ways to help out and was sector agnostic,” says Aparna Piramal Raje, 42, “when the folks at Dasra introduced me to Armman.” Daughter of VIP Industries’ Chairman Dilip Piramal and business historian Gita Piramal, Raje did her homework, met with Dr Aparna Hegde, the NGO’s founder, and spoke with experts in the field, all through Dasra.

“Often we see that because of the increased focus on ‘impact’ and ‘numbers’, donors only want to support a programme, but not the NGO. But if the NGO doesn’t have the right infrastructure in place, how will the programme go on? It takes an enlightened donor to understand this,” says Noshir Dadrawala, CEO at the Centre for Advancement of Philanthropy, a Mumbai-based organisation that specialises in charity law and good governance practices for non-profits. Menon of the Gates Foundation concurs. While a new wave of giving is taking over, “philanthropy needs to invest in the future of philanthropy”, he says. “We need tens of hundreds of Dasras, Ashoka Universities and other such organisations.”

“Often we see that because of the increased focus on ‘impact’ and ‘numbers’, donors only want to support a programme, but not the NGO. But if the NGO doesn’t have the right infrastructure in place, how will the programme go on? It takes an enlightened donor to understand this,” says Noshir Dadrawala, CEO at the Centre for Advancement of Philanthropy, a Mumbai-based organisation that specialises in charity law and good governance practices for non-profits. Menon of the Gates Foundation concurs. While a new wave of giving is taking over, “philanthropy needs to invest in the future of philanthropy”, he says. “We need tens of hundreds of Dasras, Ashoka Universities and other such organisations.” Meanwhile, newer avenues like impact investing are opening up. A form of investing that seeks to generate both a social benefit as well as a meaningful financial return, it is still “a nascent area”, says Yatin Shah, co-founder and executive director at IIFL Investment Managers. “But it will grow in time to come. Our clients’ children are asking questions and exploring ways to give effectively and meaningfully,” he adds.

As the philanthropic landscape evolves, one constant remains: “For all the talk about giving, I actually get so much back in terms of intellectual stimulation, learning, fulfilment and pure joy,” says Raje.

That’s a benefit that can’t be measured.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X