The very very special playbook

The life mantras that helped VVS Laxman, one of India's most elegant batsmen, navigate international cricket are applicable well beyond the field

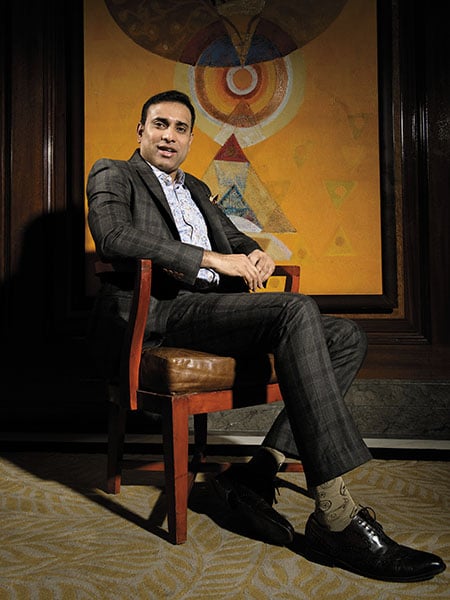

Image: Amit Verma

At 17, Laxman was faced with a difficult career choice: Take up medicine, the profession of his parents; or, play a game that had a 50:50 chance of bringing him recognition, but certainly not enough money to be chosen over medical science. Back then, cricket wasn’t a game of astronomical pay cheques as it is now, and medical science was considered to be the safe option. That he chose cricket, and his parents backed him unconditionally despite them being a middle-class family, was no less daring than Facebook founder Zuckerberg’s decision to drop out of Harvard University.

In hindsight, the risk worked out well. Really well. And Laxman doesn’t just have close to 9,000 Test runs to prove it. He has also introduced to Indian cricket a number that has come to symbolise a paradigm-shifting moment in the game: 281. That’s his score against Australia in a Test match at Kolkata’s Eden Gardens in 2001. In what was arguably the biggest comebacks in the history of cricket, Laxman, along with Rahul Dravid, carried his bat through the fourth day to not only pull India back from the brink of defeat, but also shape a generation’s approach to tough situations.

For Laxman too, that was the most definitive innings of his career, as is evident from the christening of his recently-released autobiography 281 And Beyond. In it, he chronicles his 16-year journey in international cricket, and the years building up to it, and gleans lessons that transcend the cricket field to spill onto other walks of life.

It’s always the big picture:

While 281 is indeed a number that Laxman now owns, on that morning of the fourth day of the Kolkata Test, it wasn’t about the number of runs. Both Dravid and Laxman had collected enough runs in January that year, with Dravid scoring a daddy hundred and Laxman a double century against the West Zone in a Duleep Trophy match in Surat. But in this Test, time was what mattered. Laxman had come into the match fresh from a back injury and Dravid had just recovered from viral fever. And the two had to play out the day, surviving world-class bowlers like Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne, and a team that had 16 consecutive wins to its name. “The post-tea session was particularly challenging. We were dehydrated and physically drained,” recalls Laxman. “In these situations, I always remember soldiers fighting on the border. And then you realise that the challenge that you are facing is nothing.”

Focus on means, not the end:

The analogy of soldiers is one that Laxman’s father, V Shantaram, would frequently draw. Laxman mentions a particularly painful time in 2001 when he picked up a right cartilage tear during a tri-series in Sri Lanka. The team management requested Laxman to play since biggies like Sachin Tendulkar and Sourav Ganguly were out due to injury and suspension, respectively. Should he stand the test of 100 overs? If the soldiers could, he should too, his father told him.

Perspective is something that Shantaram grilled into Laxman, right from the time he picked cricket and gave himself five years to excel in (else he would go back to studying medicine). Like, during those years, his parents never asked if he was scoring plenty of runs or winning enough matches. All they wanted to know if he was improving as a batsman. “Those five years, my entire focus was on becoming a better cricketer. That’s why I never had a moment of self-doubt about whether I was good enough. Results are just a byproduct,” says Laxman. His conviction was vindicated as he became a constant fixture in the age-group games, and subsequently created a generous buzz in the ‘maidan’ playing for Andhra Bank in the Hyderabad Cricket Association league.

VVS Laxman hits one to the fence during his knock of 281 against Australia at the Eden Gardens, Kolkata, in 2001. He surpassed Sunil Gavaskar’s record of the then highest Test score (236 not out) by an Indian before Virender Sehwag eclipsed him in 2004

VVS Laxman hits one to the fence during his knock of 281 against Australia at the Eden Gardens, Kolkata, in 2001. He surpassed Sunil Gavaskar’s record of the then highest Test score (236 not out) by an Indian before Virender Sehwag eclipsed him in 2004Image: Shaun Botterill / Allsport via Getty Images

To play on a known pitch, with your friends and relatives cheering for you from behind the boundary line, is one thing. When Laxman decided to play in the Bradford League in England in 1995, the most competitive league after the county championship, it not only meant staying away from home—“I was anyway doing that since 12”—but playing in an atmosphere where competition was cut-throat. “Everyone expected you to perform, because you were paid to do it,” he says. “If you did not score runs one Saturday, no one would talk to you until you scored the next Saturday.”

The battle was tougher outside the cricket field as well, Laxman recalls. The Hyderabadi was a vegetarian, who didn’t know how to cook. He survived the first week on baked beans, toast, cornflakes, chocolate, and “whatever was available in the supermarket”. Not just food, but everything else that was taken care of at home, had to be done independently. “Being a sportsperson, I would dirty my clothes, so I had to go to the launderette regularly. I was given a three-bedroom house, where I was living alone before Mumbai’s Amol Muzumdar joined me. That had to be cleaned. It wasn’t just cricket,” he says.

His fightback in England started with a pressure cooker and his mother’s recipe book. And the pieces started falling into place. Laxman not only ended up doing his own chores, but also took up part-time work—night shifts at a petrol pump, which ended with mopping the floor and keeping it clean for the next shift. “It wasn’t for money, but pushing the envelope,” he adds. “I figured it’s like playing cricket only, you know. When you are out there in the middle, you are the one responsible for your decisions. It was exactly how it was meant to be here as well. When I returned from England, I had changed. I was confident and independent.”

Often, risks are worth it:

The Bradford League in England was a risk that paid off for Laxman. But it wasn’t the only one. It’s a risk that made Laxman a cricketer, when his parents, goaded by his uncle, gave him the freedom to choose the game over academics. But a bigger moment of reckoning stared at him in March 2000, just two games after his first Test century against Australia in Sydney, when he was dropped for the second Test in the home series against South Africa. He mulled retirement, feeling a little hard done by the selectors for wielding the axe after failure in just one Test.

When he went back to the drawing board with his uncle to identify the problem, it came down to him opening the innings. “Opening didn’t come naturally to me. I was a non-regular opener, so the minute I failed, I was dropped,” he says. “We figured I could get a longer run only as a middle-order batsman, because that was the position where I made most of my runs.”

But the Indian middle-order at that point was packed with superstars like Dravid, Tendulkar and Ganguly, all of whom captained the team. Should Laxman really give up a position in the national team just to harp on his core competence? Yes, Laxman decided. In the difficult trade-off between retirement and risk, Laxman chose the latter, even if that meant wrapping up his career as just a first-class cricketer. “Every decision you make in life has an element of risk, and cricket teaches you that. Each shot you play involves making a decision and each decision can be risky. Doesn’t mean you don’t make them.”

In the difficult trade-off between retirement and risk, laxman chose the latter, even if that meant wrapping up his career as just a first-class cricketer

Faith in peers is a good thing:

Once he took the decision to stick to the middle-order, Laxman became a constant fixture in the Indian side, scoring 16 of his 17 Test centuries in the position. In the 225 Test innings that he played, over 150 were in positions 5 and below, which also meant that more often than not, he had to bat with the lower order and extract the maximum out of them. From an opener to No 4, one sets the tone of play; No 5 onwards, one has to react to a situation and align their game plan.

For Laxman, it was finding a way around the opposition plan of denying him boundaries and allowing him only singles to bring the weaker lower-order batsman on strike. How would he prolong his innings with the support of the bowlers for whom batting was only a secondary skill? “By giving them confidence and letting them take more strike. You can do all the pep talk in the dressing room, but if you don’t show confidence in their abilities in the middle, all that comes to a nought,” says Laxman.

Of course, he was blessed with bowlers in the team who took pride in their batting. His contemporaries Anil Kumble and Harbhajan Singh have notched up one and two Test centuries, respectively. But Laxman wouldn’t even hustle batsmen of lesser repute, sometimes leading to the criticism that he never took charge of the lower order. “If you let them play more, you are telling them that you trust them. Trust and responsibility bring out the best in anyone.” Why that’s a good thing was amply clear in the doggedness of Ishant Sharma during a cliffhanger against Australia in Mohali in 2010: Ishant played 92 balls to support Laxman at the other end to win the match for India by one wicket.

Communicate, don’t overcommunicate:

But there would be times when he would need to step up with the lower order. Like the Australia match, when Sharma asked him to shield him from Mitchell Johnson. In such cases, communication is key. “You need to tell your partner if you aren’t comfortable with a bowler. I would then take a lion’s share of the strike,” he says.

But one has to know where to draw the line of communication. With his giant partnerships with Dravid, for instance, Laxman says they would hardly need to spell things out besides the occasional fist punches to keep each other going. “Like the fourth day of the Kolkata Test, when we were losing focus because we were tired. So between overs we spoke to each other about taking it over by over.” But would they do it every other time? Laxman refuses. “Each one of us were recognised batsmen who knew what our roles were. And each one had their own method of going about it. We would never interfere in each other’s game. The beauty of partnerships lies in letting each person achieve the goal their own way.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)