The making of Vikas Khanna

From chhole-bhature and small-town Punjab to Michelin stars and Manhattan, Vikas Khanna travelled intrepidly into the unknown and emerged arguably as India's food ambassador to the world

It takes just about a minute to make it from the entrance of the national crafts museum in Delhi to the cafe inside. Even less if you make a dash for the cooler interiors, given that the temperature outside is hovering around 35 degrees Celsius. Except if you are walking in with Vikas Khanna.

The Michelin-starred chef of New York’s modern Indian restaurant Junoon—who has cooked for the Obamas, the Dalai Lama and recently served a seven-course meal for Narendra Modi and top CEOs when the Indian PM was visiting the US—is polite to a fault with every starry-eyed visitor. He acknowledges anyone who gives him a knowing smile, stops to shake every hand that’s extended his way and acquiesces to every photo request that diners make dropping their food midway. The only offer he turns down is the one to help him carry his pile of clothes for the photo shoot that is to follow; he swats the request with a wave of hand and asks, “May I help you with your bag instead?”

That dismissive hand gesture is back minutes later when the waiters at Cafe Lota bring him the menu. “Kuchh bhi chalega. Do-teen plate kuchh order karenge aur sab mil-baat ke khayenge [Anything will do. We’ll order a few items and share among us],” he tells him.

Perhaps the concept of the unpretentious sharing platter is reminiscent of Khanna’s childhood memories of a langar (a free, communal kitchen for the Sikhs), which he would frequent with his biji (grandmother). Over the years, he has often returned to the langar in his hometown Amritsar, filmed it in his documentary Holy Kitchens and replicated it in the US, too, most notably at Times Square, in the aftermath of the Wisconsin gurdwara shooting in 2012 that killed six people. Asked by the White House to spread awareness about Sikhism, Khanna chose culinary allusions over stodgy homilies to contain flared-up communal emotions. Not just because he interprets religion “from a non-religious perspective”, as he puts it, but because, in his life, whenever the going has gotten tough, Khanna has always sought refuge in the kitchen.

Take his club foot, for instance, a condition of misaligned legs that he was born with in November 1971. Despite a surgery in his infancy in the middle of the Indo-Pak war, Khanna, the son of a video cassette library owner, had to wear wooden shoes till his teens. While that allowed him to break crackers with his feet during Diwali, the ungainly clogs subjected him to ridicule from his peers. The deformity also impaired his ability to run; it imposed on Khanna a stay-at-home childhood, shadowing his biji in the kitchen. And that’s where his initiation into cooking began. “At that time, people thought it was crazy that I was being taught to cook and wash utensils. Biji was the only one supporting me in those early years,” he tells ForbesLife India as we sit down to an unhurried meal and conversation.

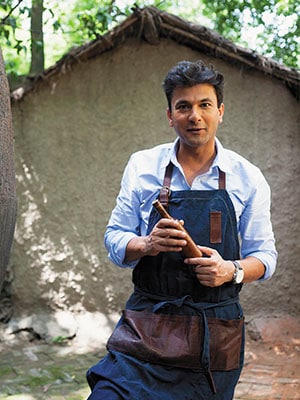

Photograph Courtesy Vikas Khanna

Woman behind the successful man: As a child, Vikas Khanna was a regular at the langar with his biji (grandmother). When he began to learn cooking, she supported him wholeheartedly

It was a decision that he didn’t regret. Nearly 35 years on, Khanna has not only taken Indian food to the world with award-winning restaurants in New York and Dubai, he is also the most recognised Indian culinary face on the global stage. With his multi-hyphenated career—that of a chef, writer, TV show host, filmmaker, what have you—Khanna has ensured that he leaves behind a legacy that goes much beyond, say, nailing spices in a dish or cooking seafood at the right temperature. But, if you ask him, the unassuming chef would sum it up as “all in a day’s work”. He would much rather talk about his days in biji’s kitchen and the early adversity that has defined his approach to food.

In 1984, when Khanna turned 13, his braces came off and the doctor pronounced him “free to run”. By then, he was too much in love with rolling the roti to do anything else. At that time, his mother and he would go from school to school selling chhole-bhature. During this process, the principal of a school contracted the duo to make 580 sweaters to help them raise money for their catering business. He didn’t know knitting, but such was his determination to earn enough to start a business that he sat in his searingly hot room in Amritsar and picked up the skill from his biji.

At 17, with Rs 15,000 in pocket from the sweaters he sold, he bought his first tandoor and set up his business, Lawrence Gardens, in his backyard. “I was beside myself with joy. So much so that I didn’t even mind that the hoarding read Gardns. I painted the ‘E’ myself,” says the 44-year-old chef. “Now, some show plates at Junoon cost $300, almost equal to the money I started my business with. It’s funny how life comes a full circle.”

*********

At Lawrence Gardens, Khanna was living in a zorb, hosting kitty parties and wedding banquets. His most prized possessions were 24 chairs and 24 white plates. The chef spent his after-banquet hours scrubbing the plates over and over to keep them spotless. Till his uncle came down from Ireland and burst his bubble.

He took Khanna to Delhi, his first journey to a big city, and treated him to the midnight buffet at ITC’s Maurya Sheraton. The food famously brought him down on his knees and moved him to tears. For the first time in his life, Khanna realised that there was life beyond his tandoor. It was at his uncle’s insistence that he applied for a degree in hospitality management from the Welcomgroup Graduate School of Hotel Administration in Manipal, Karnataka. But the challenge that came next was far bigger than any he had faced so far.

Having been born and brought up in Amritsar, Khanna could only speak Hindi, a rather Punjabified one at that. Admission to the course hinged upon his performance in a group discussion and a personal interview. He flunked both. YG Tharakan, then a member of the faculty at the Manipal institute and also of the interview panel along with late principal Sundaresh Prasad, says Khanna failed to articulate in English even basic details about himself.

Even Khanna sensed the unimpressed vibe at the interview. After he walked out of the room, he plonked himself on the corridor outside the principal’s room and bawled his eyes out. “I had told my family that now I am going to get trained in Manipal, and later set up the best Indian hotel (in many parts of India, a restaurant is still called a hotel) in the world. Now, I didn’t know how and where to go back to.”

It took him a while to calm his frayed nerves. Tharakan, now a professor and dean at Le Cordon Bleu School of Hospitality at GD Goenka University, Delhi, remembers Khanna walking up to him and Prasad in the evening, when the two were seated at the campus restaurant, and narrating to them in Hindi his passion for food. “It convinced the two of us that he indeed had a flair for cooking and we decided to admit him,” Tharakan says.

Later, during the annual day speech, Prasad explained why he eventually granted Khanna admission despite the botched interview. “He said he realised my passion for food was genuine. Everybody told him it was a mistake to let me in,” says Khanna. “He replied, saying it would be a sin to not let me in.”

*********

His language skills, or the lack of it, meant that in college, Khanna had to seek refuge in the familiarity of Indian cuisine. Tharakan, who taught him food and beverage production in his three years at Manipal, recalls how a polite and reticent boy, occasionally singing a Tamil song or two, would assume a different avatar in class, questioning the methods used to prepare classical Indian dishes, for instance, butter chicken. “While tasting and evaluating the food made in class, I could always see Vikas doing something different from other students in terms of taste or presentation. This memory comes back to me when I watch him in Twist of Taste (a culinary series on Fox Traveller) in which he recreates traditional recipes with his own touch,” he says.

It’s this twist up his sleeve that Khanna uses in Junoon to transform something like the plebeian khichdi into a $30 dish served with a variety of mushrooms—“expensive pink ones among them”—and garnished with a shaving of truffle. “Nahi banaana hai mujhe butter chicken [I don’t want to make butter chicken]. Instead, won’t you enjoy an idli injected with caramelised date pieces and a hot fig sauce?” he asks.

Such inventive fusion cooking, which marries Indian tastes with Western techniques and ingredients, has earned Khanna plaudits from his Western colleagues. “Vikas gives the West a soft introduction to Indian cooking. Most in the West believe Indian food to be limited to naan bread, butter chicken and spicy curry. His recipes take us beyond these stereotypes, but in a manner relatable to us,” says Gary Mehigan, the host of MasterChef Australia, where Khanna has made an appearance as a judge. His slow-cooked chicken tikka, for instance, cleverly recreates the taste of chicken masala or tandoor by smoking the meat over charcoal along with star anise, other spices and clarified butter. “The western palate is familiar with this smokey flavour and it’s easy to do that at home, over barbecue or coal,” adds Mehigan.

But such finesse and sophistication didn’t come easy to Khanna, who has grown up on—and still loves—the simple methi-aloo subzi. When he was at Manipal, he hadn’t even heard of a Michelin star. It was only by chance, while flipping through a magazine, that he came across an article on the culinary equivalent of an Oscar and why it was still a far cry for any Indian chef. He walked up to Tharakan and asked him how one could earn the prized tag. The professor was succinct with his answer: “Work hard.”

Khanna finished college in 1994 as one of the better culinary students of the batch, but his lack of proficiency in English came back to haunt him during placements. The first company to visit the campus was ITC. And he was rejected in one of the preliminary rounds of their multi-tier selection procedure. “They asked me to name a variety of cheeses. I told them I could write them, but couldn’t pronounce. Obviously, I wasn’t selected. Back then, our people were trained not to become good Indian chefs, but to be good corporate chefs and serve in big five-star hotels. This has changed thanks to top chefs like Sanjeev Kapoor and Tarla Dalal, who have validated our profession,” says Khanna, now the author of 23 cookbooks, including the 16-kg gold-crusted Utsav in which he chronicles rituals and culinary cultures from across the country.

He eventually ended up at Leela Kempinski in Mumbai, but left it in 1995 to return to Amritsar and Lawrence Gardens—“my dream that my parents were struggling to keep alive”. And for five years after that, he was back in his zorb again.

*********

Left to himself, Khanna would still be kneading dough, rolling bread and feeding “Punjabi aunties” with a smile. But then came a defining moment in his life when his brother Nishant introduced him to Richard Bach’s seminal work Jonathan Livingston Seagull and narrated how the protagonist, a bird learning to fly, pushes boundaries for greater glory. “Drawing parallels, my brother pushed me to be successful at the global level. He told me there’s no greater country in the world than the US that supports creative freedom and freethinkers. And my sister Radhika was the one to support me emotionally and help me make it through in the US every day,” he says.

Pumped, he chose the US as the stage to prove himself, even though it meant uprooting himself from his comfort zone. The American visa office staff in Delhi told him they had seen many an impulsive “weekend visitor” such as him. But Khanna, in his broken English, managed to convince them with his impassioned plea: “I told them I am not coming back, that I wanted to set up the best Indian restaurant in the US and that was my only dream.”

On December 2, 2000, Khanna landed at New York’s John F Kennedy International Airport with no job offers, barely a few dollars and an ambition that dwarfed all odds. “In one sense, his success story is not so different from that of so many other Indians who go abroad with virtually nothing. But most of them manage in businesses that traditionally don’t require them to be hip and glamorous. That’s where Vikas’s story stands out,” says Vir Sanghvi, journalist and food writer.

Initially, a small restaurant that he went to didn’t need chefs but had an opening for a dish washer. Khanna agreed to take up the job. Not what he wanted, but a start alright. But he was thrown out in no time, the day he was asked to step in as a waiter. “I couldn’t speak English at all. Who knew Wild Turkey was a drink and not a meat dish?” he asks.

Out of a job, Khanna used to make ends meet by doing odd jobs—helping elderly people walk their pets and working multiple part-time shifts at a small cafe in Tribeca, Lower Manhattan. He recalls one Christmas Eve when, with just about $3 in his pocket, he had to choose between paying for food and travel.

Nearly 15 years later, sitting down on the dusty grounds of the crafts museum in Delhi to pose for the photo shoot, Khanna almost laughs it off. “America mein toh yeh sab karte hai. Udher toh presidents bhi college ke time pe waiters thhe [Everybody faces hardships in America. Even presidents have waited tables during their college years],” he says. But walking down the sidewalk on that bitterly chilly day, mulling whether to pack his bag and return to Lawrence Gardens, he did begin to doubt Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Only fleetingly, though, till he joined a flock of men queuing up in front of what later turned out to be New York Rescue Mission, a shelter for the homeless. Hours later, soaking in the warmth of a blanket they gave him, Khanna decided to dig in his heels.

He stayed put in that shelter for over two weeks. It was during this time that, along with one of his fellow Indian inmates at the shelter, he received an order to cook an appetiser for a yacht party. The humble dhokla that he made on the assignment earned him the executive chef’s job in Salaam Bombay, an upscale Indian restaurant in New York, and marked the beginning of his turnaround.

When Khanna set off from Amritsar, he also packed in his bag the entrepreneurial zeal that kept him busy since his early teens. Bitten by it, he gave up the job at Salaam Bombay after four-and-a-half years and struck out on his own. He wrote cookbooks and catered to households for about a year. Eventually, he set up Tandoor Palace, an Indian takeaway located near Wall Street, serving cheap meals to professionals in New York’s financial hub. But the business started hobbling soon: With the downturn in economy, work visas for Indians started to dry up. As the appetite for desi food spiralled downwards, Khanna stopped earning enough to sustain his hole-in-the-wall venture. “There were days when the restaurant would be absolutely empty for dinner,” he says.

In the meantime, one of his regular customers, Jennifer, came to him with an offer. At that time, British chef Gordon Ramsay was looking for an Indian chef for his show Kitchen Nightmres, and Jennifer was working as a producer on the show. Would Khanna be interested in meeting Ramsay, she asked? “I said I can meet him provided he meets me after lunch service, not anytime before,” says Khanna with a sheepish grin.

In their very first meeting, Khanna floored the expletive-spouting British chef with his telegenic appearance. “He asked Jennifer, ‘Where the hell did you get this guy?’ And then he turned towards me and asked me, ‘Do you work in movies?’”

*********

In 2007, Khanna made his debut on the small screen, a space that would become his happy hunting ground in the years to come. He spent about three minutes on air, speaking one sentence in English so terribly that it left him acutely embarrassed, even forcing him to take tuitions later on. But by that night, the American press was knocking on his doors having discovered one of the most camera-friendly Indian chefs in the world.

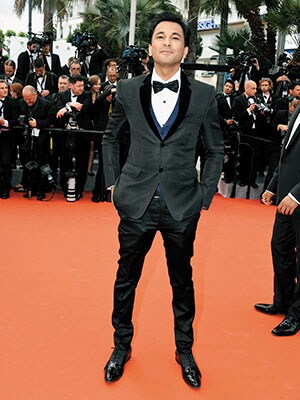

It’s a similar reaction that Khanna—named one of People magazine’s sexiest men alive in 2011—continues to evoke nearly a decade on. When he visited the sets of MasterChef Australia, remembers Mehigan, the women contestants turned into a bunch of “giggling girls”. “Here was Matt [Preston], George [Calombaris] and I cut from the same cloth, and there was Khanna at the other end of the spectrum. The audience, the press, love him because he has such a pleasant personality,” he says.

Khanna—who is still single—has made many more TV appearances in India and abroad since, starring in Ramsay’s Hell’s Kitchen, Throwdown with Bobby Flay, The Martha Stewart Show and MasterChef India.

Sanjeev Kapoor, who has worked alongside Khanna in MasterChef India and is himself a doyen of Indian television for over two decades, says, “Much before he started on Indian TV, I had met Vikas through a friend. One of the first things I told him is that he should be on TV. My hunch, which came from the experience of working on TV for so long, told me here’s a person who would click with the medium.”

Khanna’s Tandoor Palace shut soon after Kitchen Nightmares was aired, so did his catering company Tulsi and the cooking classes that he would organise. But the show gave him Dillons, the restaurant that he was in charge of turning around on the show. Khanna extended his role from reel to real and transformed Dillons into Purnima, meaning full moon; it later received two stars from New York magazine. Eventually, Purnima, too, shut down due to issues related to the building lease. But soon, Khanna found another lease of life, one that catapulted him to a role that still remains his primary identity.

In 2007, around the time Khanna appeared on Kitchen Nightmares, Rajesh Bhardwaj, a food entrepreneur and restaurateur in New York, was shortlisting chefs for his new venture—a restaurant that would redefine the perception of Indian cuisine in the city. Till then, barring a few exceptions, Indian food had never really taken off in America. Indian restaurants were considered old-fashioned and cheap and the food was never on par with first-grade cuisines.

For a while, Bhardwaj had been running Cafe Spice, a successful, modern brasserie, but he wanted to scale up to an Indian fine-dining restaurant where the food would be Indian and everything else—the service, ambience, etc—global. His son Akshay, an aspiring chef then, had watched the Ramsay show with Khanna and suggested to his dad that he could be roped in for Junoon. Bhardwaj’s friend Vipul Mallick, who had dined at Salaam Bombay, connected him with Khanna.

“I had already interviewed a few chefs, some of them established by then, but none of them fit my bill. I wanted someone fresh, without the baggage of experience, who I could groom as a brand. Besides, I am a hands-on person and wanted somebody who wouldn’t just cook well but would be actively involved with the restaurant. Vikas was just that kind of person,” says Bhardwaj.

On December 2, 2010, 10 years to the day Khanna landed in New York, Junoon opened its doors at Flatiron district, a neighbourhood in New York’s tony Manhattan, with Khanna leading its open kitchen. Almost immediately, it drew rave reviews. Sam Sifton, reviewing the restaurant in The New York Times in 2011, wrote that its style “hints at the kind of European-style sumptuousness that used to be common to upscale restaurants in Manhattan”.

The ultimate recognition for the restaurant came sooner than Khanna could imagine. Within 10 months of its launch, in October 2011, Junoon earned a Michelin star, the first of the five consecutive ones that it has earned to date. Khanna attributes this achievement not to his “delicate tandoor dishes” or the “silky three-lentil shorba” that received generous praise from Sifton, but to the generation of Indian parents obsessed with giving their children a good education. “I was not working alone to get this Michelin star; with me were my parents, an entire generation of parents who sacrificed their pleasures to groom kids to bring international awards to the country. This is the essence of my India,” he says.

*********

A few months before Junoon received the Michelin star, Khanna got an opportunity to cook at possibly the most powerful seat of power in the world: The White House. The official residence of the US president was hosting a Hindu Americans’ conference in July 2011 and Khanna, who had founded Sakiv (a non-profit that focuses on critical, global issues) in 2001, was partnering with the Hindu American Seva Communities to cook for the event. The Iskcon-inspired vegetarian fare he served up made headlines back home in India, where he was yet to make a mark. In a few months, he started hosting Season 2 of MasterChef India, replacing Bollywood actor Akshay Kumar from the first season, and ensured that he became a household name in the country where food is a great binding factor.

He cooked for US President Barack Obama again in 2012, during a charity fundraiser at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York. By then, Khanna had made it to the top league of chefs in New York, putting Indian cuisine on the same high table as French and Japanese. “Us fundraiser mein maine Indian khaane ko $38,000 per plate becha. Benchmark toh isi se he banta hai [At that fundraiser, I sold Indian food at $38,000 per plate. That’s what sets the benchmark],” says Khanna. “I also make sure our tasting menus, made with same or higher quality ingredients, are at the same price as French restaurants. Besides, I am working hard to make Utsav, a book on Indian cuisine, the most expensive one.”

While, on one hand, he was splashed all over the media for rubbing shoulders with heads of states and top leaders, Khanna was often seen traversing the country, reaching lanes and bylanes of Indian cities and towns to hunt down local flavours and traditional recipes. He’s passionate about his work and will gladly brazen out 40-plus degrees in Dubai for a shoot without a fuss. And his innate humility ensures he does not take his celebrity status seriously. “It takes him exactly 10 seconds to break the ice with anybody and walk into their kitchen,” says Shruti Takulia, a creative director at Fox India, who has worked with Khanna on several shows. She remembers a shoot at Delhi’s Chandni Chowk that was interrupted by a lady who invited Khanna to come and eat with her. Later, when the crew broke off for lunch, Khanna walked all the way back to locate her house amidst a warren of lanes and share a meal with her.

As Vir Sanghvi puts it, “Vikas is proof that you can make the best in America without abandoning your Indianness. From being a nice Punjabi boy from Amritsar to dining at the White House, he has nearly attained the impossible. It’s because of him that Indian food has become glamorous in America.”

Not only has Khanna rebranded Indian food, he has also silently answered his critics. Once, Khanna’s British manager had dissed his book and told him that the modern generation will never find Indian food sexy. By now, Khanna would have answered him many times over.

(This story appears in the Nov-Dec 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)