Can these startups fix rural healthcare in India?

A handful of startups is using technology and on-ground interventions to strengthen rural primary health care, but impact might be limited without government intervention

Shreyans Mehta, co-founder of MedCords, has built an end-to-end channel that helps villagers access doctor consultations, medicine supply, follow-ups and digital storage of their health data

Shreyans Mehta, co-founder of MedCords, has built an end-to-end channel that helps villagers access doctor consultations, medicine supply, follow-ups and digital storage of their health dataImage: Amit Jaan for Forbes India

Growing up in a family of doctors in a village in Rajasthan’s Jhalawar district, Shreyans Mehta knew that it is loyalty that often creates legacy in rural health care. In the absence of trustworthy doctors nearby, most villagers spent between ₹800 and ₹1,000 to go to cities for treatment, while others suffered at the hands of local quacks. So when his father could not go to the hospital to see patients because of a slip disc in 2014, Mehta made sure people could reach him over phone and video. The experience prompted him to travel across villages in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh (UP), Madhya Pradesh (MP) and Bihar to find answers to a couple of questions: To what extent could technology improve accessibility of health care in remote rural areas, and how can it be scaled up?

Mehta says visits to these villages and meetings with local public health officials made him realise that neither the people nor the government had any health care records or data. “I wanted to find a solution to help villagers find local doctors from similar cultural backgrounds who can understand them, and whom the patients can trust. I even wanted to help people digitise their records, so that it becomes easier to identify and predict health trends,” he says.

The 30-year-old Mehta also understood that any health care solution in rural areas cannot just solve one problem. “If I help people consult a doctor, but don’t improve their access to medicines and follow-ups, they will end up going to the cities again,” he says. So, along with friends and fellow engineers Nikhil Baheti and Saida Dhanvath, Mehta launched MedCords in 2017 in Kota, Rajasthan.

The cloud-based health management platform not only connected people to doctors and facilitated follow-up consultations but also roped in the nearest medical stores to ensure people received the prescribed medications. Going a step further, the trio launched a platform called Sehat Sathi for local pharmacists. This was for people who did not own or know how to operate smartphones. They could go to the nearest medical shop and schedule a consultation with the help of the shop owner, who was often someone they recognised and were comfortable with. “When it comes to technology, some human touch and hand-holding are necessary in rural areas,” says Mehta.

MedCords raised seed funding of $1 million from Info Edge and WaterBridge in 2018. It started monetising its services only in January through affordable yearly and per-consultation subscription models through its app Aayu, which also stored health records digitally. In March, the startup raised another $3 million through angel investors Info Edge, WaterBridge and Astarc Ventures. It is yet to turn profitable.

“Today, we have 30 lakh registered patients from Rajasthan, UP, MP, Bihar, Maharashtra and Gujarat; 5,000 registered doctors and about 16,000 local medical stores on the platform,” says Mehta, whose startup got a huge push due to the Covid-19 lockdown that made people look for health care options either online or nearest to them. “We used to get about 3,000 calls daily on the 24x7 helpline that was set up to assist people navigate the platform. And when Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about Atmanirbhar Bharat, we felt we were on the right track—that a hyperlocal, end-to-end channel powered by technology is a feasible and scalable solution to many problems in rural primary health care today.”

Abhishek Verma and Garima Dosar have built Avni, an open source tech platform that allows NGOs worlking with on-ground health workers to collect, track and analyse data

Abhishek Verma and Garima Dosar have built Avni, an open source tech platform that allows NGOs worlking with on-ground health workers to collect, track and analyse dataImage: Gaurang Dosar

According to the 2011 Census, about 69 percent of India’s total population lives in rural areas. On paper, the public health system in these regions is an elaborate structure with multiple levels: First, sub-centres that cater to about five villages with a population between 3,000 and 5,000 people. Then there are primary health centres (PHCs) for every six sub-centres, followed by community health centres (CHCs), sub-district and district hospitals. Then come the medical colleges.

However, a report titled Strengthening Public Health Delivery, published by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) on August 17, suggests that the public health system suffered from several issues, including shortage of skilled doctors and nurses, auxiliary nursing midwives (ANM), Assisted Social Health Activist (ASHA) and anganwadi workers, besides lack of equipment and diagnostic tools.

Moreover, out of a total of ₹67,112 crore, the Union health budget allocation to the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in 2020-21 was ₹27,039, a 3 percent reduction from the estimated amount.

Various other shortcomings have been observed. As per 2018 data from the ministry of health and family welfare, there is a shortage of 32,900 sub-centres, 6,430 PHCs and 2,188 CHCs. At the same time, there are only about 9 lakh registered medical professionals, which indicates a 46 percent shortfall of doctors, and an 82 percent shortfall of specialists, including surgeons, gynaecologists, physicians and paediatricians across PHCs. Experts say the reasons not many qualified doctors want to serve in rural areas include poor working environments, facilities and remuneration.

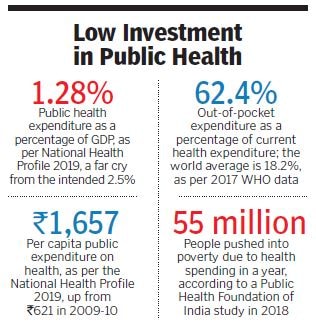

“India’s health policy focuses on rural PHCs in design, though the delivery has not been particularly great due to poor resourcing and poor workforce,” says Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI). He says the organisation had recommended that two-thirds of all health spending must go to primary health care at the local level, followed by district hospitals. “If you do that, you can meet the challenge of managing 90 percent of all health problems at the district level. But the actual spending on primary care has mostly been around 30 to 40 percent across states, with a few exceptions like Kerala.”

Reddy explains that the pandemic has thrown the spotlight back on the weaknesses of PHCs in rural areas and underlined their importance in early detection of cases and providing quick help before health conditions become more severe. “The initial panic and lack of awareness around Covid-19 created a feeling that most cases required hospitalisation. Primary health care was never on the radar and fell by the wayside,” he says. “In the last month-and-a-half, doctors and the government have realised that intensive care and ventilators are required by only 1 percent cases, and that milder cases can be treated at local PHCs and at home.”

Startups Stepping In

Covid-19 is a primary care illness, agrees Ajoy Khandheria, founder of Gurugram-based Gramin Health Care, one of the largest startups operating in this space that was launched in 2016. He has about 100 brick-and-mortar primary clinics catering to 1,000 villages in six states, and his plan of strengthening the link between primary and secondary health care has included five polyclinics that provide services including OPD consultation, gynaecology, eye care, and affordable medicines through pharmacy and diagnostic services. The pandemic has posed both challenges and possibilities for businesses like his, Khandheria says. For one, it was tough to organise personal protective equipment, gloves and other safety gear for staff in remote places. Second, a large part of the business model entailed holding camps in villages, which was affected. People stopped coming to the clinic out of fear and wanted to get treated at home. “There was no revenue for four months,” says Khandheria, whose startup has 22 doctors and 180 nurses. “The pandemic has thrown a spanner into how we operate and has been a wake-up call for players in this space.”

What has worked in their favour, he adds, is how Covid-19 has accelerated the process of digitisation. “While our model was pure brick-and-mortar in the past, we now have hybrid systems that take cost out of the system and help us work with limited clinical manpower,” he says. Gramin Health Care’s revenue model includes a digital health card that is offered at a highly subsidised cost and entitles a family to check-ups, consultations, medicine and diagnostic services for a year.

“Now that 60 to 70 percent of families are connected digitally, people need to come to the clinic to see the doctors only when they absolutely need to, which also saves the time of doctors, nurses and pharmacists. This will help us have a better, quicker chance of being profitable,” says Khandheria, who reported a revenue of $0.5 million last year and is targeting to double it this year.

“There is unprecedented opportunity for interventions offered by technology, which can transform and democratise entry management and point-of-care diagnostics, and apply artificial intelligence to ensure quality health offerings at the last mile,” says Kaivaan Movdawalla, partner-health care, EY India. India’s hospital-centric model has always focussed on sick-care at the tertiary level, which increases the overall burden of access, diseases and cost of health care. “If you focus on primary and preventive health care, anywhere between 20 to 30 percent of the overall cost of health care will come down because you are detecting issues early.”

It is this need to create impact in the rural health delivery landscape that prompted Jagdeep Gambhir, a former Goldman Sachs executive, to establish Karma Healthcare in Udaipur, Rajasthan, in 2014. “There is a gap between allocations and actual government spending on primary health care, prompting the need for private models that are outcome-oriented and scalable,” he says, adding that digital interventions are inevitable right now. Like Khandheria, Gambhir set up primary health care clinics where a trained nurse from the local community bridges the gap between people and technology, and facilitates video consultations between doctor and patients.

During the pandemic, he launched contactless consulting and designed Zoom training modules for newly recruited nurses and staff members. Karma Healthcare has 25 clinics across Rajasthan, Haryana and MP, and 50 trained nurses and outreach officers. They have treated over 1.5 lakh people till date, helped them with medication, and connected them to secondary or tertiary care services and hospitalisation, if required.

It has a user-pay model for consultation, medication and diagnostic tests, and investors include Ankur Capital, Beyond Capital Fund, Ennovent and 1Crowd. Karma Healthcare also receives project-specific grants, and has raised about $2 million in capital, and $1 million in equity to date. The revenue in the last financial year was ₹2.9 crore, and Gambhir says they are not profitable yet but “most clinics are positive at the unit-level”.

He adds that startups in this space need a long gestation period, and apart from supply of trained manpower being a challenge, capital is also not easily available. “We are looking toward insurance providers and the government for outcome-based financing that we can secure by proving impact with verifiable data,” Gambhir says.

Jagdeep Gambhir, CEO of Karma Healthcare, has created a business model that blends technology with human interaction

Jagdeep Gambhir, CEO of Karma Healthcare, has created a business model that blends technology with human interactionImage: Tarun Batra

Khandheria agrees that strategic partnerships, either with the government or other private players, are essential for institutionalising systems, achieving outcomes and economising delivery of care. “Our partnership with fertiliser cooperative IFFCO takes care of real estate, marketing and branding. We have collborations with companies including Dabur, Pfizer, Religare and Dr Reddy’s Labs for capacity building of paramedical resources, and education on prevention and treatment options of diseases,” he says. “Partnerships with local hospitals help patients with our digital cards avail treatments at a discount. So the cost of patient acquisition is reduced when it is distributed among many players.”

It was on the advice of their venture capital-backer Social Alpha that Abhishek Verma and Garima Dosar, co-founders of for-profit social enterprise Maatritva, joined hands with Bengaluru-based NGO Samanvay Foundation to merge their existing technology into a new open source platform with wider applications. Maatritva was limited to maternal care, through which the duo had trained 1,500 ASHA workers in rural Nashik to use a mobile application that identified, tracked and helped them cater to high-risk pregnancies.

The new platform Avni, which they have been building since 2018, extends to analysing child health, non-communicable diseases, common cancer screening, adolescent care and sanitation, apart from maternal health. “This product is accessible to a cross-section of people in the rural health sector, including non-profits,” Verma says. “It helps in longitudinal data collection over a period of time wherein you can flag sensitive cases, link multiple family members and trace their health histories.”

Dosar explains how, with Maatritva, they often struggled against bureaucratic hurdles in getting permissions. Plus, the app was meant for government health providers, who needed extensive hand-holding.

“But with Avni, we mostly reach last-mile workers through organisations that have established their credibility with the government. This helps us scale up implementation and receive structured feedback on what more needs to be done.” As of August, Avni was used by close to 600 organisations across the country, who in turn reached close to 3 lakh beneficiaries.  Ajoy Khandheria of Gramin Health Care says that Covid-19 is a primary health illness that has been a wake-up call for enterprises like his

Ajoy Khandheria of Gramin Health Care says that Covid-19 is a primary health illness that has been a wake-up call for enterprises like his

Image: Madhu Kapparath

All Eyes on the government

Khandheria of Gramin Health Care believes that there are limitations to private interventions and ultimately, it is up to the government to take charge of the rural primary health sector. “We [startups] cannot be under the illusion that we are big, when we cover a miniscule number of villages. India has around 650,000 villages, and even if I manage to expand way over the 1,000 villages in which I am present today, I still won’t cover even 1 percent,” he says. “The private sector can look at covering 25 percent at best, maybe more if the government encourages the big corporations to chip in.”

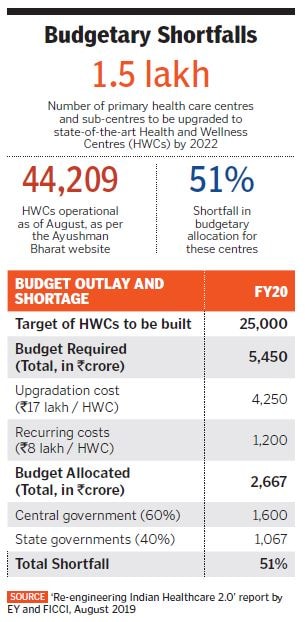

Preeti Sudan, former Union health secretary who was a key strategist for Covid-19 in the government, says not many private sector players will be willing to enter preventive and promotive health care since “it is not very remunerative”. The government has to invest, she explains. “And it is investing.” The government, Sudan says, has operationalised close to 44,000 health and wellness centres (HWC) under Ayushman Bharat. The sub-centres, PHCs and CHCs are being upgraded. “These HWCs have seen a cumulative footfall of over 20 crore people so far,” she says. “The government has responded in every manner possible throughout the pandemic. Now is the time when primary health care will receive special attention not only from across sectors, but also in the Union and State budgets.”

While Movdawalla points to a 51 percent budget shortfall for these HWCs and calls for formalisastion of employment of ASHA and anganwadi workers, Reddy of PHFI says the beneficiaries of rural primary health care are usually nameless and faceless. “So the emotional gratification for a politician comes from secondary and tertiary care, where the benefits—say one that comes from building a hospital—are more visible.”

Most countries that have weathered economic storms have invested, even during the downturn, in universal health coverage. “Look at Thailand or South Korea after the Asian financial crisis in the ’90s, or Japan after World War II,” Reddy says. “Unless you protect your productive human resources, your economy will not recover. That is the lesson politicians will have to learn and invest more widely in primary health care.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)