Finova Capital: How a husband-wife duo is rewriting rural India's fortunes

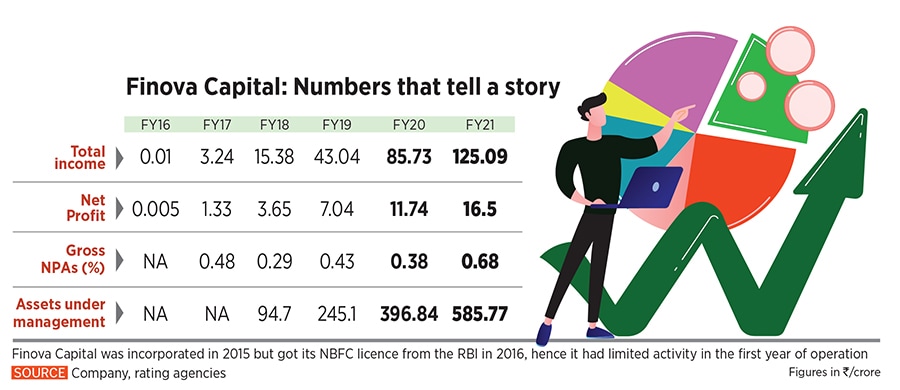

Banker-turned-entrepreneur Mohit Sahney and his wife Sunita have busted several myths while building Finova Capital. Operating entirely out of rural India, it has been profitable since inception, but the tough phase begins now as it expands its reach

Sunita (left) and Mohit Sahney

Sunita (left) and Mohit Sahney

Image: Mayur Tekchandani for Forbes India

Kesar Lal Jangid is at his furniture-manufacturing shop, Pooja Furniture, along Sambhariya Road in the heritage town of Kanota, about an hour from Jaipur in Rajasthan, waiting for some machinery to be delivered. Business activity has just started to pick up for this micro-entrepreneur after a slump in demand for housing and construction activity due to the second wave of Covid in early April.

Jangid, 38, has taken a loan of ₹6.4 lakh from Finova Capital—a Jaipur-headquartered non-banking financial company (NBFC) founded by banker-turned-entrepreneur Mohit Sahney and his wife Sunita—which focuses on lending to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). People like Jangid are new to credit and do not have a formal credit score for large banks to be comfortable for them to lend to. Finova offers MSME (micro-business) and mortgage loans.

Lending to MSMEs is one part of ‘Priority sector lending’, alongside agriculture and weaker sections of society, which commercial and foreign banks are mandated to lend 40 percent of their credit to. But for several years, most private banks have failed to meet their targets.

Jangid is Finova’s typical customer, having multiple incomes in the form of a dairy business where he bought a few cows last year; agricultural income where his family grows vegetables, besides manufacturing furniture. He earns close to ₹65,000 ($890) a month through these businesses, which has helped him pay off a third of the outstanding loan to Finova.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Finova has disbursed loans of ₹844 crore to nearly 20,000 customers through 130 branches, of which 90 are in Rajasthan and the rest in Delhi (NCR), Jharkhand, Haryana and Chhattisgarh. “We got into the MSME services segments and stayed in the rural areas,” says Sahney. Finova adds 1,500 customers each month.

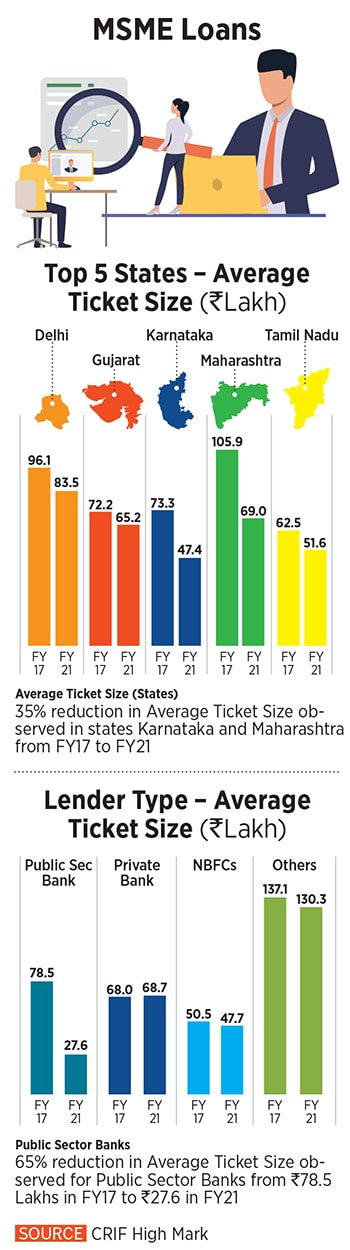

Finova has disbursed loans of ₹844 crore to nearly 20,000 customers through 130 branches, of which 90 are in Rajasthan and the rest in Delhi (NCR), Jharkhand, Haryana and Chhattisgarh. “We got into the MSME services segments and stayed in the rural areas,” says Sahney. Finova adds 1,500 customers each month. The size of India’s total lending market is at ₹156 trillion, a growth of about 100 percent from FY17 to FY21. Retail and commercial lending each contribute 49 percent to total lending, while microfinance contributes 2 percent, according to an August report from CRIF High Mark. “The [four-year period] from FY17 to FY21 can be characterised by growth of small-ticket retail loans,” the report says.

The size of India’s total lending market is at ₹156 trillion, a growth of about 100 percent from FY17 to FY21. Retail and commercial lending each contribute 49 percent to total lending, while microfinance contributes 2 percent, according to an August report from CRIF High Mark. “The [four-year period] from FY17 to FY21 can be characterised by growth of small-ticket retail loans,” the report says.