In the Crosswinds

Ajay Singh belongs to a rare breed that revels in the Herculean odds of turning around an airline

A recent study by the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) painted a grim picture for 2020 for the Covid-ravaged global aviation sector. The Montreal, Canada-headquartered agency projects an overall reduction of up to 52 percent of seats offered by airlines from business-as-usual times by year-end; passenger volumes are expected to contract by some 2.9 billion; and the potential loss of gross passenger operating revenue for all airlines is estimated at $400 billion for the year. Of this, international passenger traffic will bear the brunt of the slump, accounting for roughly $260 billion of the revenue loss and 1.46 billion of the passenger reduction. The word that comes to mind after seeing these numbers is, of course, ‘unprecedented’—9/11 and the global financial crisis of 2008 appear tame.

Till September, the Asia-Pacific region was hit the hardest, accounting for $97 billion of the passenger revenue loss of $294 billion. The projections for the whole year, too, look the bleakest for Asia-Pacific: A 72-74 percent dip in passenger capacity, and an almost $90 billion dip in revenue (on par with Europe).

As airline losses ballooned and millions lost jobs, owners looked to governments for bailouts. Many that couldn’t wrangle one were forced to shut down. Cirium, a London and Portland-headquartered travel data company, says 43 had ceased or suspended operations since January till early-October. More are expected to follow in the two months left of the year.

Yet, it’s worth remembering that aviation business models, even at the best of times, are fickle. Consider, for instance, the number of failed airlines in pre-Covid times: 46 in 2019 and 56 in 2018, as per Cirium. Add high fixed and variable costs (employees, fuel, security) to airlines’ vulnerability to exogenous events (terrorist attacks, natural disasters and, yes, pandemics), and you need to be made of stern stuff to run an airline company.

But then there is also that rare breed that revels in the midst of such Herculean odds. Ajay Singh reckons he is an entrepreneur of that unusual strain. Why else would he have ventured to buy out an airline that was submerged in debt in end-2014? Answer: To turn it around, which he duly did in a couple of years. It’s easy to point to Singh’s perceived proximity to government, but to get an airline grounded by a negative net worth of over ₹1,300 crore and a loss of almost ₹700 crore flying again takes some doing.

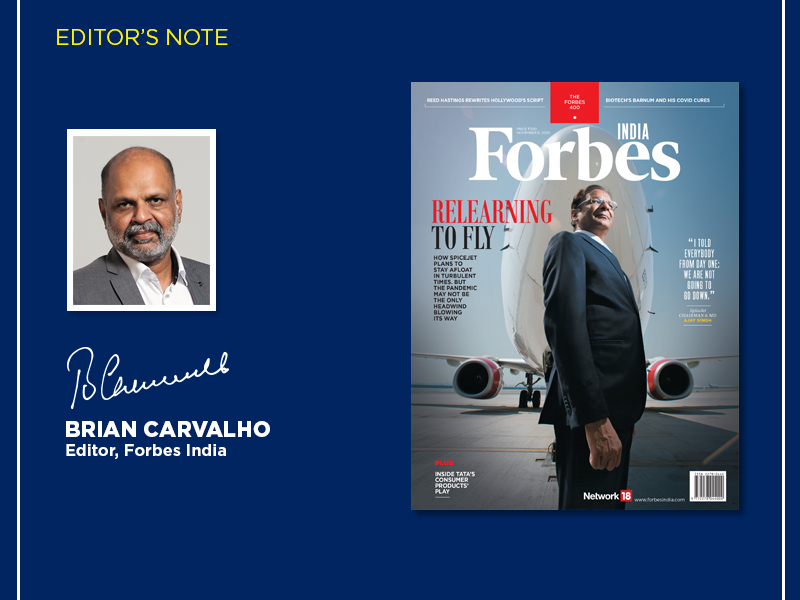

Now Singh may have to do something similar all over again. This fortnight’s edition has him on the cover, captured splendidly on the tarmac of Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport through the lens of photojournalist Amit Verma. As Manu Balachandran, who penned this story, points out, SpiceJet’s twin struggle is of generating cash and raising capital. To compound matters, two lessors have taken the airline to court in London claiming outstanding dues of over ₹200 crore. Can Singh get out of this air pocket? Turn to ‘Route Recalculation’ to find out.

Other must-reads in this issue include Pooja Sarkar’s insights into how venture capitalists and private equity mavens are doing due diligence for potential deals in India virtually from as far as New York. (Hint: Think drones.) And you just can’t miss Rajiv Singh’s freewheeling interaction with Ravi Shastri, head coach of the Indian cricket team, who has turned entrepreneur at 58 by launching a grooming label aptly called 23 Yards. “I had 22 yards all my life. For me it’s now the 23rd yard,” the outspoken coach told Singh.

Best,

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email:Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter id:@Brianc_Ed

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)