Drones Waft in a World of Virtual Deal-Making

Why VC and PE transactions are taking longer to conclude and have got more complicated and intriguing in Covid times.

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

A drone flying over Bengaluru is unlikely to have you blinking in surprise but the sight of one hovering methodically over an expansive warehouse on the tech city’s outskirts may well have you scratching your head. Well, it’s actually just another (Covid) day at the (virtual) office for deal mavens; the drone over the Bengaluru warehouse was part of a due diligence process for a global real estate fund, with eager eyes in Mumbai, Delhi and New York watching the live feed on their laptops. (Due diligence is a process investors or companies undertake to understand the commercial and financial operations of their target company.)

Welcome to the virtual, and transformed, world of deal-making in a pandemic, in which venture capital and private equity funds are counting on everything from drones to chartered aircraft before closing a transaction. As India announced the strictest lockdown measure in the world in March, private equity and venture capital fund managers were left with little choice than to move their deal making process completely virtual.

That’s an unimaginable scenario for many dyed-in-the-wool dealmakers. For instance, investment managers at Stellaris Venture Partners, an early-stage venture investment firm which focuses on series A investments with a cheque size of $1-3 million, are accustomed to spending a lot of time meeting founders of in formal settings like offices and informal ones like coffee shops and restaurants. These meetings help build a relationship and also provide an opportunity to understand priorities and decision-making processes. Such meetings were essential to evaluate partnerships with founders.

All that changed after mid-March.

“In-person meetings are a critical part of our investment evaluation process, and we have always been happy to jump on a plane to meet a promising entrepreneur,” says Ritesh Banglani, partner at Stellaris. “Now all our meetings with founders are on video, and the dynamic is very different. The meetings are more formal and agenda-driven, for one. There is lesser opportunity to just shoot the breeze and get to know each other - something I consider essential to building trust with a founder. We are still learning how to do this on video, but have now made our first two investments without in-person meetings.”

Stellaris has made two investments where the process started post-lockdown and the investors have not yet had face-to-face meetings with either of the founding teams. Banglani declined to discuss the details of these investments.

While the criteria for evaluation remain the same - the founders' ability to understand the market problem, iteratively arrive at a product solution and commercialize it at a reasonable cost -- the method seems to have changed during the pandemic. Banglani adds: “It made us challenge our own assumptions: were our readings of entrepreneurs really rooted in evidence? How much influence did the founder's personality have in our assessment? What did we really pick through in-person conversations, and how much of that was material to our decision-making? I guess we will only find out in a few years.”

While deals moved completely online, one thing that multiple fund managers, investment bankers and lawyers have told Forbes India is that the time taken to stitch a deal has increased significantly and the way deals are done across categories has changed, too.

“What used to take 4-5 weeks earlier now takes at least seven weeks. A lot of inefficiencies creep in and that’s why the timeline for due diligence has increased by 20-25 percent,” says Kuldeep Tikkha, India head for transaction diligence at EY.

For example, the likes of Stellaris or Ankur Capital, another early-stage fund, the leg work is of a different kind as they invest in early stage companies and the founders are relatively unknown. A lot of time is spent not only in understanding the founders’ goals and knowledge expertise but also their temperament as managers, their reputation, interpersonal skill sets. Things are different for private equity funds as most companies are usually backed by existing investors which gives them some comfort; but, as deal sizes increase, funds are being extremely cautious in undertaking background checks, in some cases hiring market research firms to conduct surveys and financial analysis of vendors of the target company.

As the lockdown started easing, a clutch of global private equity (PE) funds started hiring chartered planes to ferry their investment managers to assess sites and manufacturing facilities. Many funds are now allocating multiple executives from different locations across deals. Traditionally a particular set of members would travel across the country along with the lawyers to do ground due diligence. Recently a PE fund while assessing a portfolio of windmills spread across the country asked its Delhi team to visit the site in Gujarat, the Mumbai team was sent to remote Maharashtra sites and the Chennai team was flown to Hyderabad, which would have never been the case in pre-Covid times.

What hasn’t changed during the pandemic, though, is the valuation gap. “Value-wise, buyers are extremely selective about paying for companies. Buyout deals have slowed down and in the case of growth deals we are witnessing a huge valuation mismatch. And in a lot of cases, where down rounds are inevitable, existing investors don’t want to take a haircut which is further delaying deals,” says Sudhir Dash, founder and CEO at Unaprime Investment Advisors.

Dash, however, quickly clarifies that in case of information technology (IT), pharmaceuticals and digital, the story is completely different and there is plenty of interest in such deals at pre-pandemic valuations.

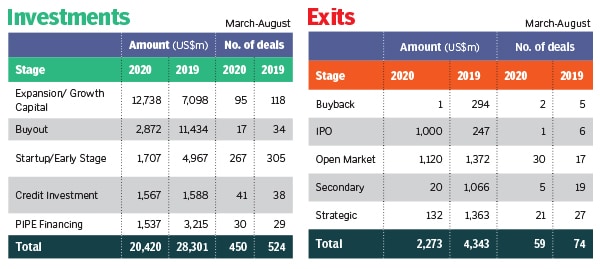

According to data from EY and VCCEdge, startup and early state firms have managed to raise $1.7 billion across 267 deals the March-August period, as against $4.9 billion across 305 deals, a fall of 65 percent in deal value. It also indicates that companies were valued significantly lower than last year.

Buyout deals have suffered the most. Funds deployed $2.9 billion between March and August compared to $11.4 billion during the corresponding period last year. This excludes growth capital deals such as the Reliance Industries transactions, which have caused an aberration in deal data for this period.

The biggest impact in terms of deal making was felt more between May and June, when people realized that this isn’t about 6-7 weeks but far beyond that, says Yogesh Singh, partner and co-head of corporate practice at law firm Trilegal.

While Singh and his team have been busy with portfolio management, business preparation, bridge finance, and structured finance for clients, Singh says activity started coming back in the infrastructure sector since June. But Singh reckons that one of the reasons buyout deals aren’t coming back in a hurry is that specialized funds are conserving cash as no one really knows how things will pan out.

“One of the conundrums facing deal making is that sellers don’t want investors walking away at a time when investors are seeking clauses to be able to move away from transactions if the target company suffers not only from a change to its assets and/or liabilities but also from a much broader set of general conditions,” says Bharat Anand, partner, Khaitan & Co.

One common factor during due diligences is representation and warranty (R&W) insurance policies, which provides cover to both buyers and sellers while doing deals to protect themselves from breach of clauses and warranties made in the share purchase agreements. The buyer usually buys it in cases where it does not have sufficient comfort from the indemnity provided by the sellers. But it has become a double edged sword these days. With diligence protocols at an all-time high and everyone being cautious, how much of risk do you really want to unearth; after all, the more risk you find, the higher the chances that some of it will not get covered by insurance.

“Transparency has increased significantly in all deals. When you look at the number projections, nothing is normative anymore. You cannot depend on your old excel projections, sales and revenue numbers, they aren’t sufficient. Past performance is no longer the harbinger of what tomorrow will be,” says Ruchir Sinha, co-head of PE and M&A at Nishith Desai Associates.

That’s why Sinha says that earlier if funds would do random sampling for channel checks of their target company, now personalized checks of the client lists and relationship status are being considered to assess their financial position. If needed, PE firms are hiring more resources for diligence. This is also driven by LPs (limited partners, who give money to PE funds) becoming more demanding and asking lot more questions.

The new lexicon that every business news reader learnt over the first few months of the lockdown is Force Majeure: Basically companies trying to wiggle out of their payment commitments citing an event or effect that was not anticipated.

Sinha adds, “This clause was always negotiated in large deals but now we are seeing this being negotiated for smaller deals too. Even in private debt transactions where Force Majeure events were generally accepted as acceleration events, borrowers are now trying to negotiate that, like natural calamities, pandemics too are reason to suspend their debt service obligations.”

While deals are being closed at snail’s pace, promoters are also trying hard to introduce clawback terms, especially in cases where there is a down round. A down round is one where the new round of fund raising happens at a lower valuation than the previous one. Capital-starved founders are introducing clauses to allow clawbacks if they meet certain targets as business prospects improve.

These clawbacks are of different types. “For example, if a growth round takes place, then the promoter will be allowed to participate at a discounted value or with partly paid shares or by giving him some convertible instruments. A lot of founders have stopped taking salaries and they are now thinking about such tools to retain value in the company,” explains Anand.

With the pandemic making many small angel and seed investors jittery, startups are also using this opportunity to provide them an exit, and replace them longer term investors. A revision in exit period and liquidation preferences are also common these days. While in distressed asset loans, a last in-first-out structure is a norm, it is now reflecting in almost all type of deals, where an investor comes in last and funds the company but takes out the money first with clauses that are more favourable than those for existing investors.

Finally as LPs closely assess the performance of their general partners and portfolio companies, raising money is becoming difficult for PE funds. LPs are now seeking more liquid assets and PE is traditionally an illiquid asset class which takes 5-8 years to return capital. Apart from this, LPs globally are now forcing fund managers to invest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliant companies.

Meantime, the lexicon for dealmakers has got thicker. Greenwashing (misrepresentation of environmental impact) is common place; the new ones making waves these days include Pinkwashing (false LGBTQ Claims), Rainbowwashing (inappropriate use of the UN’s sustainable development goals), Socialwashing (false or overstatement of labour and human rights), and Bluewashing (to portray compliance with ten principles of UN Global Compact while not doing so).

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)