MCX: Out of the Jignesh Shah shadow

Commodity bourse MCX appears to have moved beyond the Jignesh Shah-scandal hangover. New credible investors, fresh associations and a clear direction is giving India's only listed exchange a fresh lease of life

In April 2015, Parveen Kumar Singhal, the joint managing director of MCX, India’s largest multi-commodity bourse, was attending the Global Commodities Summit in Lausanne, Switzerland. But what might have been just a presence at a technical seminar at the historic lakeside Beau-Rivage Palace hotel turned out to be a coup of sorts for MCX.

Singhal, 60, a veteran with over three decades of experience across stock exchanges and regulatory agencies, spotted a stall belonging to the US-based CME Group, which owns and operates derivatives and futures exchanges. He sought a meeting with their senior managing director Derek Sammann, who was a speaker at the summit.

They met the next day. For Singhal, this was a chance to discuss, with CME, details of their long-standing strategic partnership—a licensing agreement—which was due to expire that month.

Since 2006, the CME Group and MCX have been in an agreement which allows the Indian bourse to use the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) oil and natural gas futures prices. MCX runs ‘mirror’ contracts in rupee terms, which are based on the settlement prices for the corresponding NYMEX futures contracts in the US.

The meeting was positive, and both parties emerged keen to strengthen their ties beyond the licensing agreement.

In July this year, the CME Group and MCX agreed to explore a joint viability study to set up operations at the International Finance Service Centre in Gujarat. The Gujarat International Finance Tec-city (Gift) is an under-construction central business district located between Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar; this offers financial companies and investors high quality infrastructure, tax incentives and friendlier labour laws. Economic zones such as this will compete with financial hubs like Singapore and Dubai and attempt to corner a share of the global financial services business.

The CME Group and MCX have also agreed to identify opportunities to develop new products and market them, besides implementing best clearing practices and customer education.

MCX’s licensing agreement has been extended as well.

What may appear to be an ordinary sequence of events is, in fact, a significant positive movement forward for the bourse. As Jayant Manglik, president (retail distribution) of Religare Securities, one of India’s largest commodities broking firms, says, “The relationship between CME and MCX is not new, but it would have been difficult for CME to okay this agreement earlier. Now it can extend its relationship,”

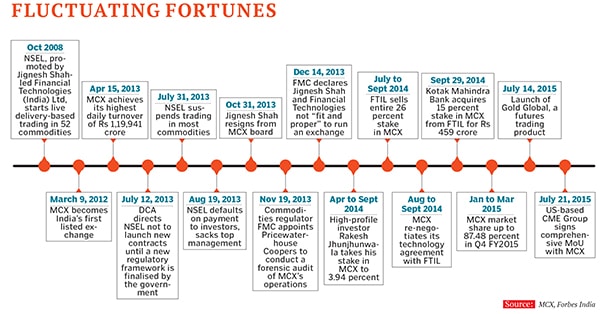

A senior MCX official agrees. “There was too much negativity in the system for any concrete steps to be taken,” he tells Forbes India. He was referring to the events of 2013, when the role of financial markets entrepreneur Jignesh Shah—the promoter of Financial Technologies (India) Ltd (FTIL) group and MCX at that time—came under the scanner after irregularities were discovered at one of Shah’s bourses, the National Spot Exchange Ltd (NSEL).

The NSEL scam is one of the largest in India’s financial market history. Over 13,000 investors lost a cumulative Rs 5,689.95 crore as a result of which they have taken NSEL and Shah to court to claim their dues. A total of Rs 379.81 crore has been recovered so far, according to August data on NSEL’s website.

At that point, India’s commodity regulator, the Forward Markets Commission (FMC), spotted several irregularities at NSEL, after independent audits. In some cases, the settlement of contracts was made well beyond the permitted 11 days. The regulator also uncovered instances of short-selling, where sellers entered into contracts without owning an underlying commodity. The contracts always registered a profit on long-term positions.

MCX, India’s only listed exchange, has not been legally found linked to the NSEL scandal and no money trail has been traced back to Shah. But FMC, through a subsequent order, forced FTIL to sell its stake in all the group’s exchanges.

However Shah, 48, had already decided to do so in October 2013.

This was a preemptive move, in a sense, since, on December 17, 2013, FMC, in a damaging report, declared Shah and his holding company, FTIL, as “not fit and proper” to run a regulated exchange or hold any position or stake at MCX and other exchanges.

Two days later, FTIL moved the Bombay High Court, challenging FMC’s ‘fit and proper’ order. This matter is still in court.

Shah, who was subsequently arrested in May 2014, has been out on bail since August 2014 and continues to face trial.

Kotak Mahindra Bank, with a 15 percent stake bought in September last year, is now the largest single shareholder in MCX, followed by Blackstone with 4.79 percent and investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, who holds a 3.94 percent stake. Foreign institutional investors hold 15.28 percent; local corporates 10.63 percent, several individual investors 31.21 percent and various mutual funds 16.28 percent, besides a minute portion by trusts/clearing members.

The fallout for MCX has been tempered by its resilience. “MCX could have got into serious trouble earlier. It hunkered down for a while, but has now come out of the NSEL crisis well,” Manglik says.

Just weeks before the NSEL scandal broke, trading volumes at the commodity exchanges in India took a hit after the government, in July 2013, re-introduced the commodity transaction tax (CTT) on bullion, crude oil and base metals. This move, aimed at earning more revenues for the government, impacted all the commodity exchanges.

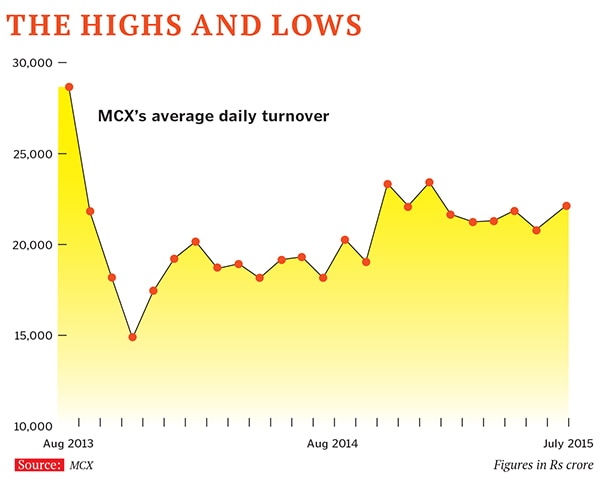

Average daily single-side trading volumes suffered a big setback of 40 percent and dipped from Rs 50,000 crore per day to Rs 30,000 crore. Subsequently, trading volumes slid to near Rs 15,000 crore per day levels after the NSEL scandal, as concern grew over the possible involvement of the then group promoter, Shah/FTIL.

But in the post-Shah era, MCX has seen a rise in trading volumes and market share (see chart). The exchange has also ironed out some weaknesses relating to surveillance and risk management, which forensic auditors had flagged off at the time of the 2013 scam.

And now with the CME exploratory agreement for new products, MCX appears to be in a sweet spot, as and when India allows for options trading and other products in commodities. “Market confidence [in the exchange] is back,” Singhal, who is also an MCX board member, told Forbes India.

The move by FMC to ‘ring fence’ MCX from its troubled promoters (Shah/FTIL)—by making them exit—proved to be effective for the bourse. Once the promoters left, MCX got a new, revamped board of directors, several of them being approved or nominated by FMC.

The board is now headed by FMC-approved independent director and chairman Satyananda Mishra. Apart from Singhal, the board also comprises four FMC-nominated independent directors and three more shareholder directors; there are two FMC-approved directors as well.

Apart from that, the exchange has started interacting more with customers and investors; it has become more active in introducing new products.

In July, for instance, MCX launched ‘Gold Global’, a futures product—with prices linked directly to global markets—that helps bullion dealers and export firms hedge their risks in global and local markets. Also, analyst interactions with the exchange are on the rise, which would have been difficult earlier, during the troubled times.

The entry of new investors—Kotak Mahindra Bank and Jhunjhunwala—has increased confidence about the future of the exchange. MCX is now UBS Global Research’s top mid-cap pick while several firms like HDFC Securities, ICICI Securities and JM Financial Services have all placed a buy rating on the stock. MCX’s stock price rose to Rs 1,050.45 at the BSE on August 13, 2015, 32.9 percent up from August 2014 and 64.13 percent since the NSEL scam broke on July 31, 2013.

“MCX has maintained its leadership even through the turbulent phase over the last two years,” UBS analyst Gautam Chhaochhoria says in a note to clients. “With falling commodity prices (in recent months), the volumes uptick at MCX has more than compensated for the lower prices. We believe MCX is well-positioned to deliver secular growth.”

In its full-year earnings for the financial year ended March 2015, MCX reported a consolidated net profit of Rs 125.76 crore, on revenues of Rs 222.48 crore. It reported a loss of Rs 34.26 crore for the quarter ended June, largely due to an exceptional provision and loss relating to an investment in MCX-SX. MCX’s top five traded commodities were crude oil, gold, silver, copper and natural gas, accounting for 87 percent of trading in the January to March quarter. UBS, in its latest report, forecasts a 30 percent rise in volumes for FY2016 and 50 percent for FY2017.

Tightening of costs has contributed to this upturn: FY2015 saw MCX lower costs and other expenses. Software support charges (what MCX pays to FTIL for its technology) fell by 38 percent to Rs 38.30 crore in FY2015, from a year earlier.

Last year, MCX and FTIL entered into a new technology supply contract (reducing the duration from 99 years to eight years) which will now expire in October 2022. The new contract means that MCX pays FTIL Rs 1.3 crore per month, instead of the Rs 2 crore it used to.

Legal expenses more than halved to Rs 6.46 crore while warehouse facility charges fell by 90 percent to Rs 68 lakh, according to March-end full year earnings data.

After the NSEL scam broke, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) was directed by FMC to conduct a special audit of MCX, from inception in November 2003 to September 2013. The purpose was to identify the role of ‘related parties’ and risk management systems at the exchange. The PwC report said: “The operations of MCX appear to be significantly dependent on FTIL and its group companies, whether it relates to providing the exchange ecosystem framework (for technology solutions and warehousing) or selection of vendors for non-trading transactions.”

The report had also identified questionable trades between MCX and related parties. PwC highlighted “various control lapses or weaknesses in the technology platform of MCX, which potentially diluted its ability to detect participants’ involvement in manipulation”. Other areas of weakness related to the alert system.

MCX has not challenged the veracity of the PwC report.

Internal data available with Forbes India shows that MCX has strengthened its risk management and surveillance systems through real time monitoring of price alerts like last traded price (LTP) compared to the previous LTP. It has also advanced the funds pay-in time to 9.30 am (before market starts) from 10.30 am, which would help strengthen financial risk management.

It has implemented the ‘self-match prevention’ facility to curb self-trades—where the buyer and seller are the same individual—aimed at creating artificial volumes and manipulate prices. The exchange has also made its firewall policy more stringent to prevent cyber attacks.

Steps taken by MCX after the crisis have not gone unnoticed. “MCX has taken steps, after independent audit reports. Its board and audit committees are more proactive,” Ramesh Abhishek, chairman of FMC, says. “Market confidence in MCX is strong.”

Once the Kotak Mahindra Bank deal was complete, FMC, in September 2014, approved the extension of the contract launch calendar for MCX for FY2016 and FY2017 in 27 contracts across key commodities.

Amid all the positive changes, MCX has one unresolved concern—and that is people-related. After the NSEL scandal, when Shah was out of MCX, key personnel like Shreekant Javalgekar (the then MD & CEO), Dipak Shah (director-market operations), Hemant Vastani (chief financial officer) and Sumesh Parasrampuria (director-business development) and others put in their papers.

Things deteriorated after that. In May 2014, the then MD and CEO Manoj Vaish quit MCX, after just three months of being in charge, citing health reasons. This was just after the exchange released portions of PwC’s final audit findings. “Manoj Vaish’s leaving was a major blow; the market perceived that something was seriously wrong at the exchange,” says Singhal, who was forced to cut short his three-month US holiday and take charge as interim CEO in May last year. Until then, Singhal drove business development strategies and interacted with regulatory agencies.

“The morale was at its lowest at this point,” he says. And he should know. After all, he has seen the highs and lows of the Jignesh Shah-led era. A former director on contract at FMC (2006 to 2008) and, prior to that, executive director and CEO of the Delhi Stock Exchange (in 2001), Singhal had a ring-side view of Shah’s rapid rise as an entrepreneur and the expansion of his empire with eight exchanges in the commodities and stock markets.

Singhal was approached by Shah to join MCX-SX, which he did in 2009. A year later, he joined MCX as deputy managing director. MCX insiders say that Singhal was twice offered the charge of the exchange, but he refused since he was close to retirement age.

Singhal will now serve on the MCX board till October 2017.

“[Manpower-wise] the worst is not over for the exchange. We are in immediate need for more senior people, including a CEO. The exchange has no clear succession plan at the moment,” Singhal says.

In May this year, FMC shot down MCX’s proposed appointment of Balasubramaniam Venkataramani (BSE’s chief business officer) as the new MD and CEO, as it had not followed “the process laid down”. A selection committee will now be formed to restart the process.

Despite the disarray, Derek Sammann of the CME Group is looking at the broader picture, one in which MCX, with an 87.48 percent market share in the January to March quarter, could continue to play a dominant role. The NCDEX (National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange) is a distant second with a 11.52 percent share and the balance 1 percent is held by a mix of smaller national and regional exchanges.

The timing of CME’s MoU with MCX is significant, say analysts. “CME continues to repose faith in MCX,” says Vivekanand Subbaraman, an analyst with HDFC Securities.

CME Group offers the widest range of global benchmark products across all major asset classes, including agricultural commodities, metals and energy. It also has a strategic partnership with the National Stock Exchange (NSE), based on license agreements for benchmark US and India equity indexes. “There are mutual benefits that both CME Group and MCX can derive from working closely together,” Sammann told Forbes India in an email. “The global importance of India’s economy and its position as one of the engines of global growth have made India a compelling and key market for CME Group.”

This association also comes at a time when the governance of India’s commodities markets is to come under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi). India’s government has cleared the way for FMC’s merger with the markets regulator. Analysts are betting on a further boost to reforms and the introduction of new products, similar to what Sebi has achieved in India’s equities markets. “When the Sebi-FMC merger happens, the new regulator will look at newer products. This will be positive for India’s markets, how positive is unclear at the moment,” says HDFC Securities’ Subbaraman.

Commodity options account for only 13 percent of total derivatives volumes globally, a UBS 2015 study shows, but the proportion is expected to be much higher in India when these are allowed. They base this on the success seen at the NSE, where options—first introduced in 2001—account for around 79 percent of futures and options (F&O) volumes and much higher than global equity exchanges.

Given the prospect of a crisp and more conducive policy and regulatory market environment, MCX is showing signs of an institution starting to breathe easy. Its position as a market leader is back, with higher volumes and market share, and the dark ghosts of the NSEL scam appear to be moving away.

It is at the threshold of a new beginning, ready to become version 2.0, and that too, without a promoter—or even a CEO.

But this could be its most interesting phase too: With new shareholders, who will soon seek to operate in a new regulatory regime, and with the potential for sharper growth with newer products.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)