Staying power of CLP Holdings

CLP Holdings is one of the few international energy companies that has managed to weather the many challenges in a sector that has seen many a foreign player stumble

They came, they saw and they moved on.

That sums up the story of most foreign power producers who were keen to tap the burgeoning demand for energy in India over the last decade.

Besieged by policy and regulatory issues, the power sector remains one of the most unattractive sectors for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country. This is despite energy being one of the few sectors where 100 percent FDI is allowed. The challenges companies face include stringent land acquisition laws, lack of fuel linkage, inadequate tariffs and poor financial health of state-run energy distribution firms (commonly referred to as state discoms), that are the largest buyers of power produced in the country.

It’s little wonder then, that global players have shown a tepid response to the power play in India. German energy producer E.ON, for instance, which was looking to enter India through an acquisition a few years ago, eventually shut its office in the country in 2013. Others like Spanish firm Iberdrola were reported to have been looking at investment opportunities, but no concrete transactions have materialised, yet.

Even the few foreign power producers that operate in the country have a skeletal presence. American power firm AES, one of the first to enter India in 1993, has scaled down operations to a single power plant in Odisha. More recently, French firm GDF Suez entered India in December 2013 by acquiring a majority stake in Meenakshi Energy and Infrastructure Holdings’ 300 Megawatt (MW) plant in Andhra Pradesh, which has another 700 MW under development.

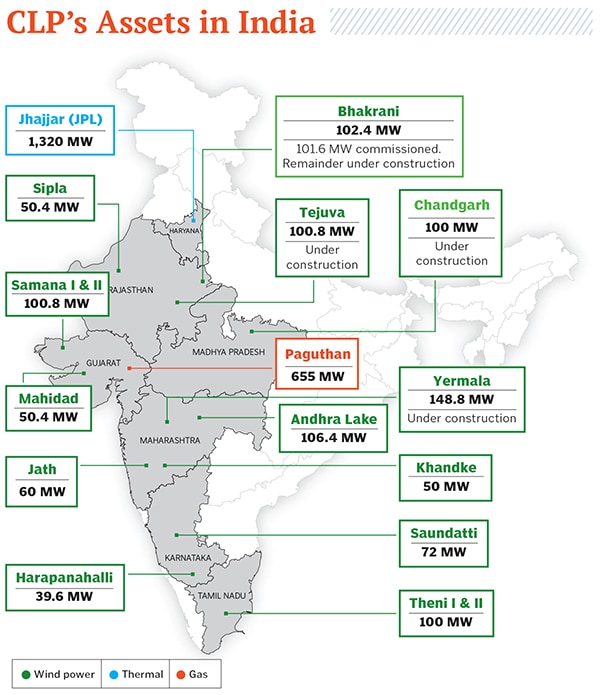

But every rule has a few exceptions. One international firm has bucked the trend by staying invested in India for nearly 20 years and growing its portfolio to a meaningful size of 3,000 MW: CLP India, the domestic arm of Hong Kong-based power producer CLP Holdings. To date, the Rs 73,760-crore energy company has invested Rs 14,000 crore in India and has emerged not just as the largest foreign power producer in the country, but also the largest producer of wind power. It operates a conventional gas and a coal-fired power plant, too.

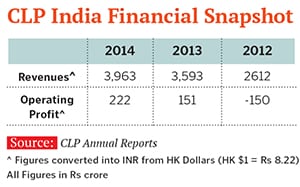

According to industry experts, CLP India has earned a place among the top 10 power firms in the country by overall installed capacity. It reported an operating profit of HK $270 million (around Rs 222 crore) in the calendar year 2014, up 47 percent from the previous year. Its revenues in the same period stood at Rs 3,963 crore, around 10 percent higher than in 2013.

The key ingredients to its success, relative to global peers, include long-term support from a patient global parent, a cautious approach in bidding for projects to ensure that the firm does not overstretch itself, a strong local management team equipped to make independent decisions and timely diversification into renewable energy that has helped offset the vagaries in availability of fossil fuels. Buoyed by its success in Asia, CLP Holdings has realigned its global growth strategy and, along with China, has identified India as one of the primary growth markets where it seeks to expand. The power company also operates in Australia, Taiwan and Thailand, among other countries in the Asia Pacific region.

“Post Enron, there were only two foreign power companies active in India—CLP India and AES—for the longest time. CLP India has done better than AES as conservatism has helped it remain active in India over a longer period,” says Arvind Mahajan, partner and national head of energy, infrastructure and government practices at KPMG in India.

It, then, isn’t far-fetched to suggest that the company can serve as a foreigner’s guide to the power sector.

Slow but steady

CLP began its journey in India in 1998 by picking up stake in a 655 MW gas-based power plant located in the Bharuch region of Gujarat. The project was originally promoted as a joint venture with the Torrent Group, Powergen of UK, Siemens AG and the Gujarat government. In 2002, CLP India acquired full control of the power plant, which it renamed Paguthan Power Station.

Given that CLP has been present in India for 17 years, a portfolio of nearly 3,000 MW does not seem very big. Some of its private sector competitors have established double the power-generating capacity in half the time. Reliance Power (R-Power), for instance, has a commissioned capacity of 5,945 MW. The power generation arm of the Anil Ambani-led Reliance Group raised around Rs 11,200 crore through a public issue in 2008 to build its plants, and commissioned its first power capacity in 2009.

But then, chasing top-line growth by rapidly expanding capacity has never been CLP India’s priority. Instead, the goal is to consistently improve the profitability of Indian operations by executing fewer projects that have the potential to generate stable returns over a longer period.

This is a point that Richard Lancaster, chief executive officer of CLP Holdings, reiterates during a video interview with Forbes India. “Our approach is very disciplined. We want to build a sustainable business over the long term and not necessarily chase rapid growth or scale,” says Lancaster, who is based in Hong Kong.

CLP India’s conventional power projects and wind farms have been generating stable returns. In the four years till 2014, CLP India’s operating profit has grown 17.63 percent annually. The holding company registered a turnover of HK $92.2 billion, or Rs 73,760 crore in 2014. (Around 61 percent of this turnover came from outside Hong Kong.)

That said, the company’s Rs 222 crore operating profit in India is a drop in the ocean compared with some of its local competitors such as state-run NTPC. The country’s largest power producer reported a profit before tax of Rs 10,456 crore in FY15. However, when compared to some of the larger but beleaguered power producers, CLP India’s profitability appears handsome. Adani Power, part of billionaire Gautam Adani’s conglomerate, had a consolidated net loss of Rs 815.6 crore in 2014-15. It has been struggling mainly because its flagship power plant in Mundra runs on imported coal from Indonesia, prices of which shot up unexpectedly following a change in the country’s national policy on natural resources.

CLP India has decided not to diversify its conventional power portfolio much because of uncertainty in procurement of coal and gas, and problems with acquisition of land. But another important reason is the frail financial health of various discoms, which are often not in a position to purchase power due to lack of funds.

The other crucial factor that saw CLP India fall behind some of its competitors (in terms of conventional power generation capacity) was the bidding behaviour of some Indian private sector companies while attempting to secure government projects. “Some of the bids that we saw were, frankly, quite astonishing. Companies were willing to accept risks that we hadn’t seen being accepted anywhere else in the world,” says Rajiv Ranjan Mishra, CLP India’s managing director since 2004. “There was no way that an international company could accept those kind of risks. That is why we were not able to expand our investments in conventional power in the manner that we would have liked to,” adds Mishra, who is based in CLP India’s headquarters in Mumbai.

When the government invites bids for a power project, it is typically awarded to the company that quotes the lowest tariff, which it proposes to charge from state-run power distribution companies. This is done with a view to minimising the cost of power to end users. In an attempt to win such projects, some of the power companies bid for extremely low tariffs based on financial and operational assumptions that aren’t justifiable, such as the cost of coal remaining constant. As a result, many are now burdened with debt that they cannot service. This has also led to many power producers selling off assets. That was just the kind of situation that CLP wanted to avoid.

“It did not get caught in the euphoria that saw other power firms aggressively bidding for assets (from 2006 onwards). And that has meant that it is in a strong position to take advantage of the opportunity that renewable energy presents in India currently,” says Mahajan.

This cautious approach, however, does not mean CLP India opted out of the bidding process altogether. In 2008, it won a bid to build and operate a 1,320 MW coal-fired power plant in Jhajjar, Haryana. This was a ‘Case II bid’, which meant that it was entitled to government support to secure fuel and land for the project. The plant was also given coal linkage from one of the mines owned by state-run Coal India.

The winning of this thermal power project bid is one of the reasons why the company has done well, says R Venkataraman, senior director at consulting firm Alvarez and Marsal India. “Since then, the company has managed to sustain [business] by being cautious about the projects they bid for, without being too aggressive. It has also smartly diversified into renewable power to mitigate the uncertainties of coal and gas availability for conventional power plants in India,” says Venkataraman, who has more than two decades of experience working with NTPC.

By side-stepping the bidding frenzy, CLP India has found itself in a position to diversify into renewable energy.

From wind to the sun

After executing a couple of conventional power projects, CLP has chosen to focus on renewable energy. It is the largest wind power producer in the country by installed capacity, with an asset base of 820 MW. Mishra says that the company’s wind power generation in India is likely to cross 1,000 MW by March 2016.

With renewable energy constituting nearly a third of the company’s overall portfolio, CLP India is one of the most diversified power companies in India. In comparison, R-Power has an operational renewable power portfolio of 200 MW (according to the latest investor presentation on its website), which is only 3.3 percent of its total generating base. Tata Power has a much larger renewable energy footprint, with an operating capacity of 1,119 MW, but that is still only 12.8 percent of its total asset base.

After creating a wide base of wind power assets across Rajasthan, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, CLP India is now gearing up to respond to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call to create 100 GW of solar power capacity in India by 2022. Lancaster points to an interesting project that CLP has undertaken in China; a model it may replicate in India, given the paucity of land. Working with farmers, it recently commissioned a solar farm in China’s Hunan province where it put up panels to generate solar energy on agricultural land, without hindering existing farming. “The farm produce keeps growing between the solar panels, opening up another source of earning for the landowners. This is an idea we can certainly look at bringing to India,” Lancaster says.

Not always smooth sailing

The two conventional power projects that CLP India operates (the Paguthan and Jhajjar plants) have seen their fair share of challenges, akin to those faced by the power sector as a whole. The Paguthan asset, which used to operate at a high plant load factor (PLF)—a key measure of operating efficiency of a power plant—of 70-80 percent, had a PLF of only 5 percent in 2015. An explanation for this can be found in CLP’s 2014 annual report: “In common with other gas-fired generators in India, the high price of gas available for use in power generation led to low levels of dispatch from the (Paguthan) plant.”

The high price of natural gas can be blamed on its dwindling supply in India. Many power producers have been forced to switch to more expensive, imported liquefied natural gas to make up for the shortfall. But with prices of imported gas dropping and the government auctioning off subsidised imported LNG to power plants running at sub-optimal capacity, the situation may improve. CLP India won some subsidised gas through an auction in May to be used for power generation during the monsoon months of June to September this year. This should help the company triple PLF at Paguthan to 15 percent.

In for the long haul

CLP India wants to sustain and, of course, improve its performance. “Our experience in India has been mixed. We have had some good investments, but at the same time we have had some issues particularly with supply of fossil fuels,” says Lancaster.

While the company may be limiting its exposure to conventional power for now, it plans to increase it in the future. CLP India is exploring the potential of building an imported coal-fired power plant at Paguthan by the end of 2018, after the power purchase agreement with the state discom for the existing gas-based plant expires.

It is also pioneering some innovative financial engineering. To raise funds, Jhajjar Power Limited, the company’s subsidiary which operates the plant in Haryana, issued asset-backed, non-convertible bonds to raise Rs 476 crore in April. It was the first time that a power company in India came out with such an offering to raise debt. Mishra states that CLP India is looking to raise another Rs 300 crore debt for the ongoing construction of its new wind farms.

He adds that if CLP India makes a single new investment in thermal power of at least 1,500 MW and maintains its historical run rate of adding 200-250 MW of renewable power in a year, it could cross a capacity of 5,000 MW over the next 3-5 years. “But that in itself is not a target,” he says.

Though CLP India is profitable, Mishra admits the profits are hardly enough to justify the cost of capital. “The cost of debt in India is 12 percent, so the equity should at least make 16 percent, right? I would say around 15-16 percent return on equity is enough. But we are far from that, and this is due to the problems we faced at Jhajjar,” he says. But he is confident that CLP India will achieve the desired level of profitability (he declines to reveal a number) by the end of the current fiscal. “If we can meet those targets, then we will have no complaints from our shareholders,” says Mishra.

And if CLP India crosses 5,000 MW capacity, it will be in a good position to compete with another international power producer that is daring to dream big in India—Singapore-based Sembcorp, which has 3,340 MW of power generation capacity under development in India, according to its website.

CLP is in India for the long haul. “We look to invest in a country with a view to building a sustainable business over time,” Lancaster tells Forbes India. And that is exactly what CLP India is aiming to do.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)