Cover story: Can Kamal Haasan replicate his success in politics?

For six decades, art has been his medium and message. Now, Kamal Haasan is leveraging his personal value to steer another all-consuming ambition: Electoral success

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India; Styling: Amritharam; Wardrobe: Antar Agni; Hair: Vance Hartwell; Makeup: Gage Hubbard

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India; Styling: Amritharam; Wardrobe: Antar Agni; Hair: Vance Hartwell; Makeup: Gage HubbardNeenga Nallavara, Kettavara?” Are you a good person or a bad person?

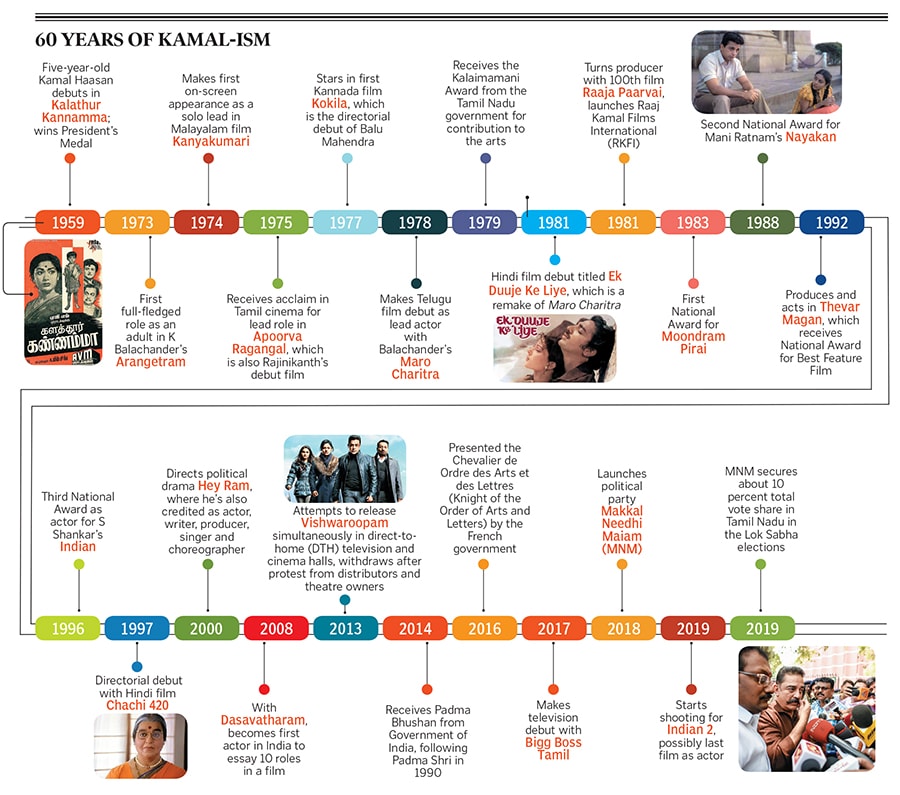

It’s funny that Kamal Haasan should be asked this question 32 years after he first faced it. In Mani Ratnam’s 1987 film Nayakan, the question triggers protagonist Velu Naicker—a commoner who turns gangster to protect his underprivileged community—to take stock of his entire life. The climactic dialogue was immortalised in Indian cinema, but Haasan, on-screen, had no answer to it. Through a performance that eventually won him a National Award, the audience learns that the existential dilemma posed by the question agonises Velu Naicker till his last breath.

Off-screen, however, Kamal Haasan has more clarity. After 60 years of making more than 200 films in five languages, Haasan believes that he is working towards becoming a good human. “It’s a continuous, everyday process. There is a challenge to that status every day… being a nallavan is a work in progress. It’ll never be complete, but I’ll never quit trying,” he tells this journalist in response to the same question. We’re in Chennai, a week after his 65th birthday on November 7.

Between launching a skill development centre in his hometown Paramakudi near Madurai (because “a school dropout could become Kamal Haasan only by acquiring a few skills”) and charting out expansion plans for his 38-year-old production company Raaj Kamal Films International (while considering himself “just an employee like everybody else, not the owner”), Haasan is also jet-setting to shoot for Indian 2. The film, to be released next year, is both a sequel to his 1996 National Award-winning vigilante drama Indian, and possibly Haasan’s swansong as an actor.

The decision, he had reiterated last December, is to make way for a bigger goal: Politics. It’s his way of engaging in public welfare service and “making Tamil Nadu the number one state in the country’’, as he puts it. So even as he believes that his earnestness sets him apart from the state’s existing political representatives, the quest now is to make people believe that Kamal Haasan is a nallavar.

Haasan’s fans and loyalists in Tamil Nadu, meanwhile, address him with a rhyming moniker: Nammavar; taken after the method actor’s 1995 film of the same name, roughly translated as ‘one among us’. They passionately spout slogans as his flight lands at airports, as he makes speeches at events, during the screening of his film, and at his every public appearance: “Enga Kamal, thanga Kamal [Our Kamal is gold],” they say: The ‘Universal Hero’, filmmaker, writer and musician who has ruled the silver screen for 60 years, and the statesman who they think will fill a supposed “vacuum” created by the passing of Tamil Nadu’s two formidable leaders, J Jayalalithaa of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) and M Karunanidhi of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). Like Haasan now hopes to do, both former chief ministers had traded successful careers in the Tamil film industry to become consummate legislators.

Out of the Box

Haasan’s unmaking as an actor and the making of a politician might have roots in his childhood, and its traces can be felt all over his illustrious film career that has garnered legendary status in India. As he deconstructs his artistic journey to Forbes India, peppered across the interaction are quotes from Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins’ Freedom at Midnight, along with multiple references to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

If his passion project Hey Ram sought to see the face of the Mahatma behind his halo, those close to Haasan believe that the actor’s views on caste, social justice, spirituality and religion (or the lack of it)—which have been routinely vocalised in films like Thevar Magan, Anbe Sivam and Virumaandi, to name a few—are the result of a childhood that was a heady concoction of early exposure to the arts and parents whose life was entrenched in the politics of the day.

Kamal Haasan as a five-year-old in his debut film Kalathur Kannamma, for which he received the President’s Medal

Kamal Haasan as a five-year-old in his debut film Kalathur Kannamma, for which he received the President’s MedalImage Courtesy: Gnanam Media

Haasan was a late child born to Rajalakshmi and criminal lawyer D Srinivasan. His eldest brother Charuhasan is 24 years his senior, while the late Chandrahasan and sister Nalini are 18 and eight years older than him, respectively. Despite academics and professional careers, each of his siblings pursued the arts, resulting in young Kamal growing up in a protected home where classical music and dance were the default ambient sounds.

“My education came from home, not from school,” says Haasan, who admits to not being a studious child. Instead, he reveled in listening to his mother play the violin and his brothers sing. He watched his sister learn how to dance. His home in Paramakudi, spread over two-odd-acres, also made room for a makeshift open-air auditorium where his parents would routinely invite music, folk and theatre artists to perform.

“He would pick up a little bit of everything,” says Nalini of her younger brother. Their parents indulged the little boy. “My father believed if the child is interested in arts over studies, then so be it. He would say that two of his sons are lawyers and his daughter is studying, so it would be good to have an artist in the house,” she recollects. In 1959, producer AV Meiyappan chanced upon a four-year-old Kamal and asked him if he wanted to act in a film. A year later, the boy received the President’s Medal for the same film, Kalathur Kannamma. And there was no looking back.

Over the years, Haasan trained in Carnatic vocals from Padma Vibhushan M Balamuralikrishna. He started learning Kuchipudi at the age of 12, and followed it up with Bharatnatyam, Kathakali and Kathak. He trained in theatre under TK Shanmugam. As a result, apart from the three National Awards he has picked up as an actor (for Moondram Pirai, Nayakan and Indian), Haasan has lent vocals to more than 30 songs and has choreographed dance sequences.

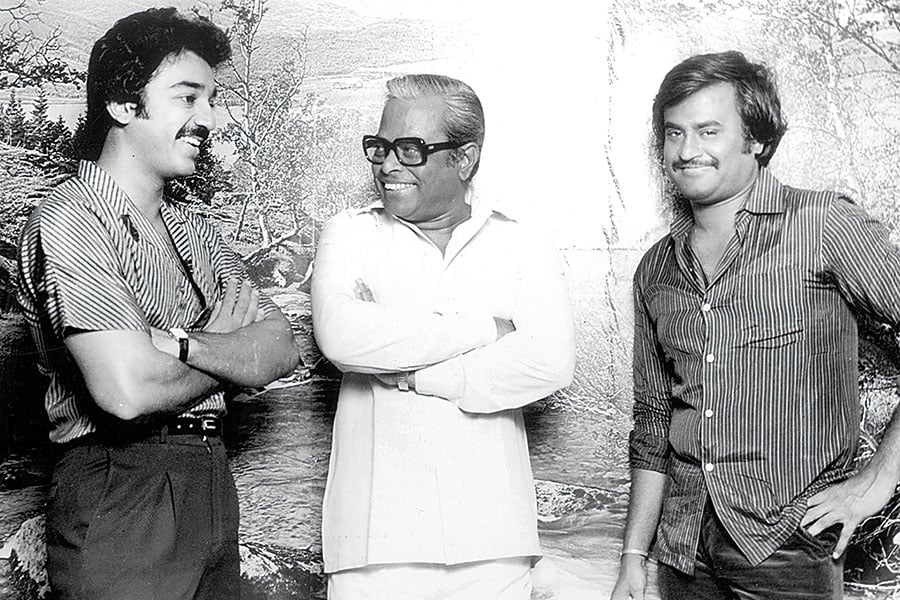

The actor with his guru, director K Balachander, and Rajinikanth (extreme right)

The actor with his guru, director K Balachander, and Rajinikanth (extreme right)Image Courtesy: Gnanam Media

Mid-career, fuelling his fondness for prosthetic makeup, he even worked as an assistant to Ameican make-up artist Michael Westmore on the sets of one of the Star Trek films to master the craft. “I don’t have a religion. So I cannot term acting or filmmaking as a ‘calling’, for even that sounds religious to me. I just fell in love with cinema, and I was one of the fortunate guys whose love was reciprocated. Not all are that lucky. Bas wohi pyaar hai, jiske badle mein koi toh pyaar de [After all, it’s only love when it is reciprocated]” he says, explaining that he found his gurus in the arts, including the legendary filmmaker K Balachander, along the way, and that standing on their shoulders elevated his view.

His early exposure to art clearly resulted in a natural career progression, and it now seems the same with his political plunge. Haasan’s father, a khadi-wearing Gandhian who opposed British rule in the pre-Independence period, was not only the legal counsel for the royal families of Pudukottai and Ramnad, but also a pioneer of education reforms credited with building the first girls’ school in Paramakudi.

Guests at Haasan’s childhood home, therefore, have included the likes of former Tamil Nadu Chief Ministers K Kamaraj and C Rajagopalachari. Dining table conversations have often revolved around the rise of the Dravidian movement, Gandhian politics, and electoral developments of the day. “My father was no Nostradamus, but he always felt I should get into politics,” laughs Haasan, recollecting how he even wanted him to give civil service examinations. “He was the only man who kept hinting at the possibility and believed that I must be trained in administration when the time comes.”

Nalini believes that her brother’s nature of doing things on his own terms without bowing to pressure would make him a good politician. National Award-winning film critic Baradwaj Rangan says these qualities have made Haasan stand apart as an actor too.

“There are stars like Amitabh Bachchan or Rajinikanth, who automatically get chosen for big projects and, hence, do not have an active hand in shaping their own careers. Then there are ‘non-commercial’ actors like Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah and Shabana Azmi who were particularly conscious of what they do and how best a film could showcase their talents. In Kamal, you have a unique blend of both,” says Rangan.

While this approach might have affected the way the distributors look at him in terms of the viability of the project, Haasan’s stardom has remained intact, according to Rangan, who is editor, Film Companion South. “He is one of the very few actors who could claim that his continuing stardom is the result of people always looking forward to what he would do differently in his next film. Most stars are just asked to do the same things over and over again,” he says.

Actor Pooja Kumar has starred opposite Haasan in three movies, including the two Vishwaroopam films. She has been around as he negotiated with Muslim groups who were unconvinced about the portrayal of their religion in the 2013 film, as he battled the AIADMK government that banned the film’s release fearing law and order problems, and has seen him remain persistent through it all. On set too, she says, the actor is all about passionately pursuing whatever he intends to achieve. “What he does, on-screen and off-screen, is very complicated, but he does it with no inhibition. And the foundation of all that is the truth, which shines through,” Kumar says.

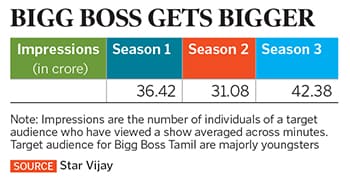

Political commentators have observed that it was after the melee surrounding Vishwaroopam that Kamal Haasan began to increasingly amplify his political viewpoints. He became more visible and vocal on social media since 2016, and two years later, in 2018, launched and became president of the Makkal Needhi Maiam (roughly translated as People’s Justice Forum).

Today, even as he is on the cusp of turning into a full-time politician after wrapping up what might be his last film as an actor, people around him feel he has much more to offer. “I feel that there is room for him to do so much more as an actor, but it’s his choice at the end of the day because he has a strong vision of who he is and where he would like to go,” says his daughter, actor Akshara Haasan. “His opinions and decisions come from a place of curiosity, being aware and thinking ahead of the times.”

Rangan says it would have been good to see Haasan go the Bachchan or the Robert de Niro way to play character roles. “Almost always, Kamal is the solo hero, or both heroes, or even all 10 heroes like in Dasavatharam. While what he has done is amazing, if he were open to playing character roles, it might have given us an interesting array of performances.”

Building the Base

What differentiates Kamal Haasan from his predecessors like MG Ramachandran and Jayalalithaa is that the latter were immersed in serious politics even before they launched or took over parties, says senior political journalist Vaasanthi, who is also Jayalalithaa’s unofficial biographer.

“MGR was an MLA with the DMK, when he realised he could stand on his own, and therefore launched the AIADMK. He had a tremendous fan-following, especially among women, because he acted in propaganda films that portrayed him as a good, noble man. Likewise, Karunanidhi, a leader of the Dravidian movement, was political from the age of 13,” she explains.

Vaasanthi believes that Kamal Haasan has successfully channelised his fan base to do social work instead of mindless hero worship. As a politician, even though he is meeting people, doing groundwork and campaigning extensively, she feels that “there might still be a distance that alienates him from the electorate because of his star status”.

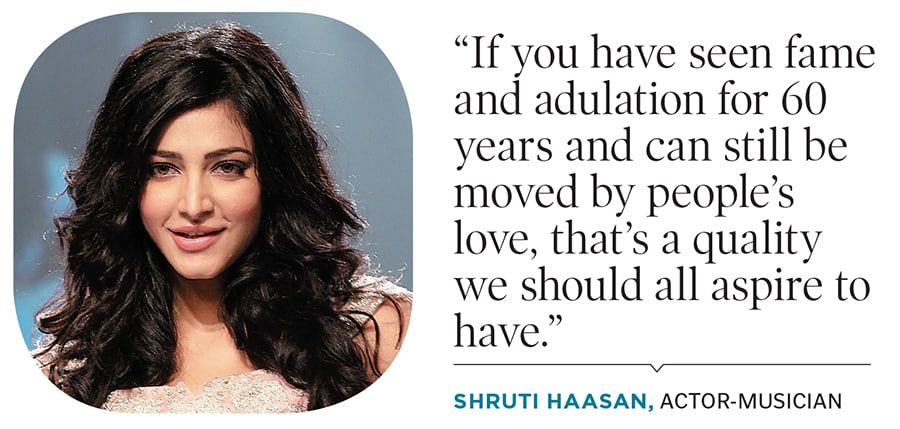

Haasan’s daughter, actor-musician Shruti, believes otherwise. “Even today, if you get emotional around my father, he will tear up. He empathises with people, listens to them and connects with their energies. And I think that if you have seen constant fame, adulation and fanfare for 60 years, and can still be moved by people’s love and their concerns, that’s a quality we should all aspire to have.”

She describes her father as a problem-solver who thinks on his feet, “but only takes calculated risks after pondering it over at least a 100 times”. Be it entertainment or politics, she continues, he has often embraced new ideas faster than others.

Haasan, meanwhile, considers himself a maverick, irreverent film buff who champions OTT. “I have been the biggest advocate of change, be it politics or cinema. My attempt to introduce online cinema almost ended my film career, thanks to the then AIADMK leadership, which had vested interest in cinema theatres and felt threatened,” he says, referring to the time in 2013 when he wanted to release Vishwaroopam simultaneously on direct-to-home (DTH) television and in cinema halls, but withdrew the plan following protests by theatre owners to boycott the film.

Becoming screen-agnostic is also the biggest strategy up the sleeve of Haasan’s Raaj Kamal Films International (RKFI), which is now making structural changes to build full-fledged teams only to handle digital media, television and live entertainment, apart from films. NV Narayanan, CEO, RKFI, tells Forbes India that the production house, working toward its 50th film, will harness various scripts written by Haasan that haven’t seen the light of day yet. “At the same time, we are trying to not depend only on Kamal sir as a star, but also utilise his genius, his creative strategy, to collaborate with talent wherever it is.”

RKFI, he says, will continue experimenting with newer technologies as it has done in the past. “For example, Mahanadi was the first film in India to introduce Avid non-linear editing technology, Mumbai Xpress was the first digital Tamil film [shot on a 3CCD camera] and Vishwaroopam was the first Indian film to experiment with Auro 3D technology,” he says. The production house also has plans to adapt the long-stalled film Marudhanayagam, written and directed by Haasan, for the digital space. Narayanan, while not revealing numbers, says RKFI is a profitable company and that as CEO, his focus is to now “build a healthy balance sheet, and a robust portfolio of films, TV and digital work”.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)

Haasan has often been vocal of his opposition to right-wing ideas: Be it reacting sharply to Union home minister Amit Shah’s push to make Hindi a common language for the country, or pointing out that free India’s first terrorist was Hindu, while referring to Mohandas Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse. Haasan also raised concerns about the passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill in the Lok Sabha. Sending out a tweet, he wondered why Sri Lankan Tamils and Muslims were left out of the ambit of the bill if it was “genuinely benevolent” and not simply a “vote garnering exercise”.

Haasan has often been vocal of his opposition to right-wing ideas: Be it reacting sharply to Union home minister Amit Shah’s push to make Hindi a common language for the country, or pointing out that free India’s first terrorist was Hindu, while referring to Mohandas Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse. Haasan also raised concerns about the passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill in the Lok Sabha. Sending out a tweet, he wondered why Sri Lankan Tamils and Muslims were left out of the ambit of the bill if it was “genuinely benevolent” and not simply a “vote garnering exercise”.