How Renzo Resso's Diesel Stormed the Blue Jeans Market

Renzo Rosso made his first billions by bringing a sexy Italian touch to the ultimate American icon, blue jeans. Now he’s building an international fashion conglomerate that could one day rival LVMH

When Renzo Rosso arrived in Manhattan to open his first Diesel jeans store, he deliberately picked a spot directly opposite Levi’s on Lexington Avenue. “I wanted to show how beautiful our product was, in front of them,” says Rosso, a mischievous grin spreading across his tanned, unshaven face. Diesel didn’t have enough merchandise to fill the 15,000-square-foot space back then, in 1996, so Rosso did what seemed logical to him and built a bar and DJ booth. “In the beginning, every few months, we’d close the store at 6 o’clock and throw a party,” he says in his occasionally impenetrable Italian accent. “And we would party.”

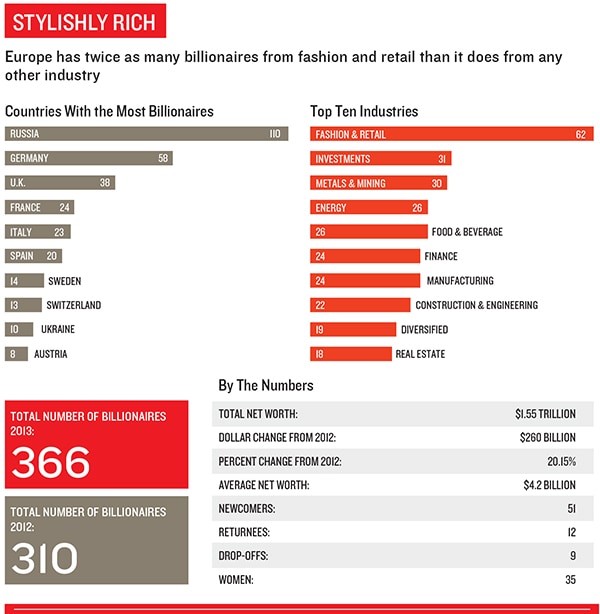

Now 57, the father of six claims he’s retired from the party circuit, but his graying blond curls, skinny jeans and knuckles tattooed with his initials give him the air of an ageing rock star. Rosso’s desk overlooks Diesel’s hulking campus, a maze of glass and steel surrounded by vineyards an hour outside Venice. From his swanky office, decorated like a pricey bachelor pad, he presides over a fashion empire that has made this farmer’s son a billionaire. He debuts on this year’s list of the world’s billionaires with an estimated net worth of $3 billion. Rosso owns 100 percent of Diesel, which has evolved from a jeans specialist to a much broader lifestyle brand (T-shirts to shades to fancy chairs) in the 35 years since its inception. Through a holding company called Only the Brave, Rosso has spent the last decade snapping up majority stakes in small, prestigious fashion houses all across Europe: Paris-based Maison Martin Margiela, Amsterdam’s Viktor & Rolf and, this past December, Milanese label Marni. Group revenues for 2012 hit $2 billion. Fashion pundits wonder what Only the Brave will scoop up next in the increasingly competitive industry landgrab that has, in the past two years, seen Italian jeweller Bulgari, suitmaker Brioni and menswear label Gianfranco Ferré sold to larger foreign investors.

In fact, the Marni acquisition followed a rare disappointment for Only the Brave. In 2012, Rosso tried to buy Italian couture house Valentino, put up for sale by London private equity outfit Permira. He was the runner-up, he says, losing out to an investment vehicle backed by Qatar’s royal family, who reportedly paid around $860 million. The bid marked the first time Rosso seriously considered seeking outside funding. “That was an important investment,” he says, perched on a $6,000 white linen sofa from Diesel’s home furnishings line. “We would’ve needed the banks.” He’s aware that to compete with Qatari money, not to mention fashion’s two French kingpins—LVMH and PPR—he may have to consider a public offering. He’s just not sure if that’s what he wants. “The size of the group is quite nice,” he says, before pausing. “Never say never.”

Rosso’s first business venture came long before Diesel, which he cofounded at 23. As a child on his parents’ farm in Italy’s Po Valley, he was given a rabbit by a schoolmate. He discovered it was pregnant, so instead of handing it to his mother to be added to a pie, he started an impromptu breeding business for pocket money.

In his teenage years, Rosso admits to having been more concerned with girls and his electric guitar than academics, enrolling in a textile manufacturing course at Padua’s Istituto Marconi because he’d heard it was easy. At 15, hunched over his mother’s Singer sewing machine, he made his first pair of jeans: Bell-bottoms, with 16½-inch flares. Soon, he was charging his friends a few dollars a pair. He remembers rubbing the stiff denim on concrete to soften it up, or distress it—a technique he doesn’t take credit for inventing, though he was among the first to use it.

At 20, Rosso joined Moltex, an Italian manufacturing outfit owned by Adriano Goldschmied, an early denim guru who went on to found his own popular line, AG Jeans. By 22, thanks in part to a $4,000 loan from his father, Rosso was 40 percent owner of Moltex. In 1978, the duo renamed the company Diesel, a nod to the decade’s oil crises, when diesel suddenly became a viable fuel alternative. The fashion pack didn’t warm to the unusual, unglamorous name right away, but Rosso is nothing if not patient. Diesel was one of the smallest of a slew of denim labels under the Moltex banner at the time, including the popular Daily Blue and Replay lines. In 1985, Rosso sensed Goldschmied wanted to focus on his more successful brands and bought his partner out of Diesel for $500,000. Struggling to break into the US market, he made an early bet that the style-conscious, flush youngsters of that Wall Street boom era would pay a premium for jeans that were brand new but looked vintage. American department store buyers weren’t so convinced.

“My cheapest pair of jeans was $100,” Rosso remembers. “This was 1986, when the most expensive pair in the US was Ralph Lauren, at $52.” Early believers included Ron Herman, whose landmark Los Angeles boutique, Fred Segal, was the first in the US to stock Diesel’s pricey pants. Herman recalls being struck by the quality of Rosso’s fabric, which he partly attributes to the location of Diesel’s factory, nestled between rivers that flow to the Adriatic. “Textiles absorb conditions from the ground up, like food,” he says. “There’s great water in Molvena. It was the denim equivalent of farm-to-table.” Soon, upmarket stores in Boston, Seattle and New York were stocking Diesel. Early on, there was always the proviso that if Rosso’s clothes didn’t sell, he’d buy them back or pay for the retail square footage wasted.

But Diesel did sell, with hockey-stick revenue growth: $2.8 million in 1985, $10.8 million in 1986 and $25.2 million in 1987. Marshal Cohen, head of apparel industry analysts NPD Group, thinks he knows why. “These were the years following Brooke Shields and her Calvins,” he says. “Denim was once casual, a working-class, down-and-dirty product. All of a sudden it was the antithesis. Ralph Lauren himself wore a sports jacket with denim. What Diesel did was create the quest for the perfect pair of jeans. As other designers entered the market, it only propelled it.”

In 1998, two years after Rosso’s brash New York launch, the Wall Street Journal anointed Diesel “the label of the moment”, citing its “emphatically European” look versus purveyors of prep like Tommy Hilfiger and the Gap. Diesel’s sleek design aesthetic went hand in hand with its savvy advertising and marketing, much of it controversial for controversy’s sake. In 2001, the company launched a $15 million print campaign featuring a fictitious newspaper, The Daily African. Black models in Diesel jeans lounged in limos or lay across mahogany desks under headlines imagining Africa’s supremacy as a world power (“African Expedition to Explore Unknown Europe by Foot”). It won that year’s Grand Prix at the International Advertising Festival in Cannes. Its 2010 campaign “Be Stupid” came under scrutiny for seeming to encourage risky behaviour. In one spread, a model stands in the middle of a busy street with a traffic cone on her head, obscuring her vision as a car zooms toward her. In another, a woman on safari, clad only in a tiny bikini, casually adjusts her camera while a hungry lion approaches her from behind. The Cannes jury handed Diesel another Grand Prix.

Martin Margiela approached Rosso in 2002. The enigmatic Belgian designer was head of what was then a cult label, Maison Martin Margiela, now known for its monochromatic, understated men’s and women’s clothes. The fashion house had stalled financially—despite $20 million in annual sales it had overspent on opening boutiques and couldn’t expand further without outside investment. Margiela was being courted by “the most important French group”, says Rosso (presumably billionaire Bernard Arnault’s LVMH, the $36-billion-in-sales luxury juggernaut, parent of Louis Vuitton and Fendi, though Rosso would not elaborate).

Rosso had bought out his own high-end manufacturer, Italy’s Staff International, two years prior. This allowed for vertical integration: In-house design, production and distribution. Staff International would help improve Maison Martin Margiela’s infrastructure, and Rosso promised not to meddle on the creative side. “I don’t want to talk about other groups, but there are groups who are buying a brand to exploit its image,” says Giovanni Pungetti, whom Rosso had lured away from Unilever and installed as CEO of Maison Martin Margiela in 2002. Luckily, Rosso wasn’t in any rush to see a return on his investment. It took seven years after the deal for the Parisian design house to turn a profit.

Rosso made an undisclosed but “quite big” investment, then went about applying some of his Diesel formula to Maison Martin Margiela. “At his core, Renzo is a merchant,” says Fred Segal’s Herman, also a friend. “It’s something grassroots: You get what people want, you sense a need and you fill it. There are very few true merchants—Mickey Drexler from J Crew, or Steve Jobs. Renzo knows the difference between what’s going down the runway versus what people will buy, like T-shirts.” Under Rosso’s guidance, Maison Martin Margiela added shoes, belts, perfume and bags to its offerings. Fans of the house’s logo-free aesthetic could now buy a $500 pair of sneakers, instead of a $1,600 blazer. Lower price points, new showrooms and revamped collections led to exploding revenues: $20 million in 2002; $100 million in 2011. The brand is now so hip that two of the most stylish men in music, Jay-Z and Kanye West, both dropped its name in recent tracks. (West, a friend of Rosso’s who makes frequent appearances on the billionaire’s Instagram feed, deserves kudos for his improbable rhyming of “Margiela” with “dealer”.)

Rosso now calls Maison Martin Margiela his “second baby”, lifting up his polo-neck to show off one of his five tattoos, this one on the nape of his neck: The company’s signature seam-stitching, four discreet lines where a jacket’s inside label would be.

In 2008, Rosso added the Viktor & Rolf brand to his Only the Brave stable. In 2012, Italian women’s wear purveyor Marni came into the fold, selling 60 percent of its shares to Rosso. Both had been on the scene for more than a decade, and both needed outside money to grow.

“I had many offers from private equity and the like,” says Marni CEO Gianni Castiglioni. “They wanted a short-term push to improve Ebitda. I wanted an industrial partner, not a financial partner.”

Today, through Staff International, Rosso manufactures and distributes clothes for a long list of respected prêt-à-porter companies, including Marc Jacobs Men, Roberto Cavalli’s Just Cavalli and contemporary casual wear line DSquared2. He took the latter, designed by identical Canadian twins Dean and Dan Caten, under his wing in 2001. “Dean and Dan are these incredibly talented guys with these crazy, amazing clothes,” explains Fred Segal’s Herman. “But they sell jeans.” So Rosso applied the formula he had used at Maison Martin Margiela. In 2006, DSquared2 added perfume and makeup to its offerings. Sunglasses came in 2008, and last year saw the addition of jewellery and scarves. Revenues have grown from $2 million (2001) to $221 million (2012). Rosso calls the Catens his “offsprings,” and was on hand in February at a Fashion Week bash they threw at New York’s Copacabana. Despite his protestations, Rosso still looks remarkably at home in a night-club, sandwiched between celebrity friends, throwing up peace signs.

Rosso’s own sons Andrea and Stefano hold down the fort while dad is on the road, which is now about 50 percent of the time, mostly commuting among European capitals in his helicopter. Andrea, 35, is creative director of Diesel’s urban, sporty spinoff new business (he was instrumental in the Marni deal, says Rosso). Both share their father’s easy manner, louche good looks and seeming aversion to shaving. Stefano also helps run Red Circle, the family’s investment fund, a play on the English translation of their surname. Through Red Circle, the Rossos are the biggest investors in Italian startup incubator H-Farm.

Rosso isn’t sure what’s next for Only the Brave. For now, he’s focussed on coming to grips with his latest buy, Marni. On his first official day as Marni’s owner, in January, he got up in the middle of the night to take a 5 am chopper to Milan. He and CEO Castiglioni share a common aim: Expansion into China, Russia and the Middle East. In 2012, Marni made 60 percent of its $170 million revenues from its own freestanding stores. Castiglioni wants to boost that number to 75 percent. He’s come to the right person. Rosso knows a thing or two about how to open a store.

Renzo Rosso with son Stefano

Chic Geeks

Through Red Circle Investments, the Rosso family is the biggest single investor in H-Farm, a tech startup incubator and venture capital fund based near Diesel’s headquarters in Treviso, Italy, with offices in London, Seattle and Mumbai. H-Farm weeds through about 1,000 pitches a year, taking ten through the development phase and selling one or two. Rosso is “obsessed by technology”, he says, although it is son Stefano who sits on H-Farm’s board. “It’s an opportunity for us to have access to the most innovative minds and talents,” says Stefano. Investments include:

NONABOX: A monthly subscription service delivering health and beauty products to pregnant women and new mothers—sort of a Birchbox for babies. It operates in Italy, Spain and Germany. H-Farm was part of a $700,000 funding round in 2012.

TILTAP: This iOS developer makes apps allowing iPhones and iPads to communicate with external sensors. The software allows doctors to monitor their patients’ vitals even when they are away from the hospital, or let landlords manage buildings’ power consumption remotely. H-Farm owns 41 percent.

MISIEDO: The Italian answer to OpenTable, MiSiedo allows iPhone or iPad users to book tables at any of 53,000 restaurants across the US. The app also allows a maître d’ to add walk- ins or phone bookings with a single tap. H-Farm was part of a $450,000 round in 2012.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)