What the Billionaires List Tells Us About Emerging Economies

Examining the rankings offers clues to which emerging economies are on the rise and which will disappoint. One key: Good fortunes versus bad fortunes

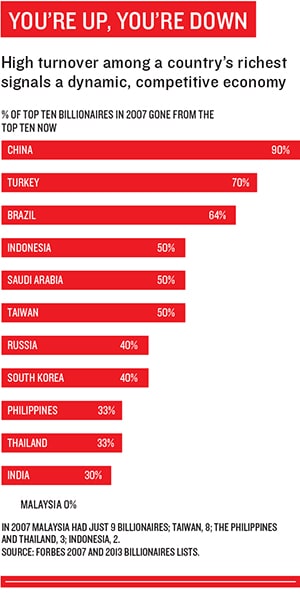

Everyone enjoys the voyeuristic thrill of Forbes’ annual listing of the world’s billionaires, but as an emerging market investor I use the list as a tool to spot what I call Breakout Nations—economies poised to beat expectations, and rivals, over the next five to 10 years. Analysing the list can provide a quick read on an emerging economy. If the billionaire class controls fortunes that are outsize, compared with the size of the economy and its level of development, it’s a sign that an economy is out of balance. And if the same few names appear on the list year after year, with no new blood, it’s a sign of stagnation.

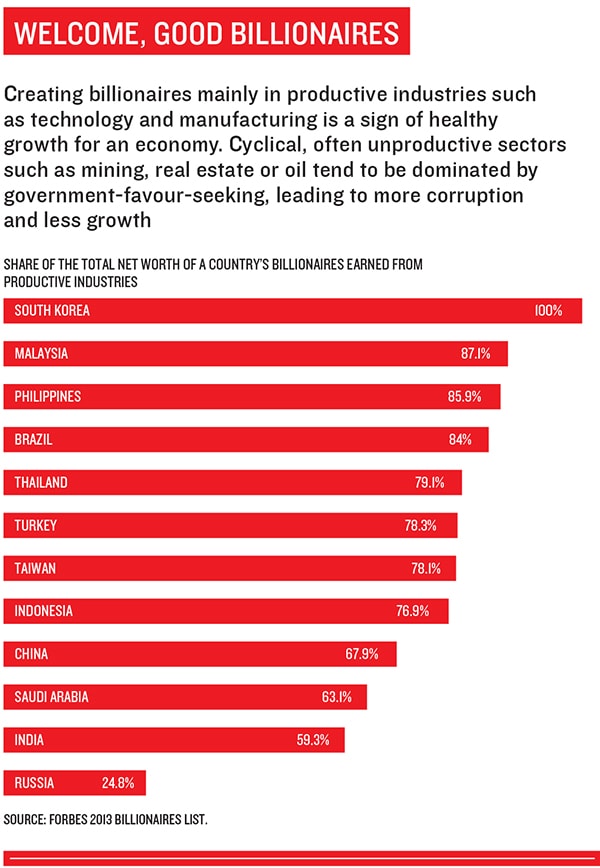

The emergence of billionaires is a good sign—if they are emerging in productive fields such as technology or manufacturing. In the 2000s, however, the world saw the rise of many billionaires who rely on government connections to build monopolies in sectors such as oil, real estate and mining—industries that traditionally contribute much less to sustainable growth because they are volatile and often prone to corruption. This type of billionaire is a bad sign.

Applying this analysis to the 2013 list yields some surprising results. For all the buzz about corruption and inequality in China, its billionaires control wealth equal to just 3.2 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP)—making this the least-bloated billionaire class among the big emerging markets. The average fortune of the top 10 Chinese billionaires is now $6.8 billion, still modest in an economy that was the single largest contributor to global GDP growth over the past decade. China also shows a healthy turnover among those top 10, with nine newcomers on the 2013 list compared with 2007. The country’s richest person, Wahaha Chairman Zong Qinghou, shot to the top this year, thanks to his fast-growing beverage business. Yet, his net worth of $11.6 billion is still smaller than the fortunes of leading tycoons in much smaller economies, including Malaysia and the Philippines.

These results may not be entirely coincidental—several men previously on the billionaires’ list have landed in jail. This suggests that the state may be stepping in to quash excessive and misbegotten fortunes, a policy akin to killing a few chickens to scare the monkeys. But they do imply that Beijing is working more effectively to foster competition and contain wealth—at least that of the ultrarich— than recent headlines indicate.

The general rule is that if the total net worth of the billionaire class surpasses 10 percent of GDP—the rough average for emerging markets—there could be a popular backlash. The Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand are now all above the 10 percent threshold, and India is on the edge, with billionaire wealth equal to 9.9 percent of GDP.

India is the most surprising billionaire story in Asia because in the global imagination it’s still closely associated with the Mumbai tech tycoons and the rising middle class of IT workers.

In the past decade, however, more and more of its largest fortunes were built by businessmen who cut political deals to corner provincial markets. India’s incomplete reform agenda has left it near the bottom, at No. 166, of the World Bank’s rankings of 183 countries for ease of starting a business. These obstacles to doing business are chasing big companies overseas and preventing small outfits from challenging well-connected tycoons.

In November, liquor tycoon Ponty Chadha, described by the press as a man who had prospered on “fistfuls of state favours”, was shot to death in a dispute over the ownership of a farmhouse outside New Delhi, an event that seemed to symbolise the rise and risks of the newly connected billionaire class.

Breaking down the 2013 list by industry yields a striking snapshot. Russia is off the charts with 75 percent of its billionaire wealth derived from classically unproductive industries such as real estate and natural resources, but India is second worst at 41 percent. This is also the one metric on which China ranks very poorly, with 32 percent of its billionaire wealth coming from unproductive industries, due in part to its raging real estate bubble.

What matters most is the direction of change for the combination of billionaire bloat, turnover and productivity, and this year’s list does carry some hopeful signs for India. The billionaires’ share of GDP has fallen by roughly two percentage points since 2011, and the average net worth of the top 10 tycoons has dropped by $2 billion to around $10 billion. This is a result mainly of recent declines in the stock market, but at least the billionaire imbalance is not growing.

Also on the upside, the country’s top 10 includes two tycoons who weren’t there in 2010, with at least one from a dynamic and productive industry: Pharmaceuticals magnate Dilip Shanghvi.

This year’s list suggests bright prospects for several of Asia’s emerging economies. In South Korea and Indonesia, billionaire wealth is low as a share of GDP. These countries also tend to have a healthy turnover among the elite, with billionaires rising in the right industries. Only one Indonesian billionaire was also on the list in 2007. In the Philippines, while the billionaire share of GDP doubled to 17 percent between 2012 and 2013, some 86 percent of that wealth came from productive industries.

The global rise of “bad” billionaires since 2000 has been epitomised by the reversal in fortunes of tech tycoons and energy barons. As growing demand from China pushed up commodity prices, particularly for oil, the energy barons rose to the top.

In 2001, the world had 29 billionaires in energy (mostly oil) and 75 in technology. In 2011, that ratio was reversed: 91 in energy and 36 in technology. This year, those numbers have shifted again as China slows.

There are now 93 energy billionaires and 95 in technology. And more billionaires have been rising in the energy sector on the strength of technology, particularly the new methods to tap oil and gas trapped inside shale rock. So energy is increasingly a technology story.

The billionaire analysis is going to get much more interesting. Only a decade ago, China had no billionaires; now it has 122, so the billionaire data is becoming more significant over time. It’s worth watching closely, particularly for new faces and for good billionaires emerging in productive industries.

Ruchir Sharma, author of Breakout Nations (Norton, 2012), is head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)