They're Making Car Parking Easier

Soon, when you drive to a mall, all you might have to do is punch a card to park your car. Bid adieu to long queues and wasted fuel

Soon, when you drive to a mall, all you might have to do is punch a card to park your car. Bid adieu to long queues and wasted fuel

If you live in a city and drive a car, chances are your parking travails will resonate with millions of others in India. The experience may range from delayed meetings to deflated tyres (the act of angry residents); fines in no-parking zones, stolen valuables to even vehicles getting towed away from that no-man’s land — the space that borders on the parking and no-parking zone.

With 800,000 cars and 15 million two-wheelers being added to Indian roads every year, finding a place to park is an everyday battle.

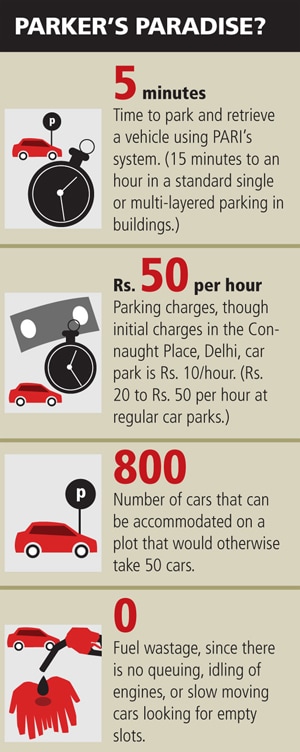

But residents of Delhi, especially those who work or live in Connaught Place, could be in for some respite. From sometime in July, a fully automated public car parking system on Baba Kharak Singh Marg will allow 1,400 cars to be parked on eight floors of a 10-storey building (two floors will have a shopping complex).

Car owners will punch a card and leave their vehicle at an entry point pallet (a steel plate). A lift will move the pallet to an available parking slot. On return, owners will punch their card again and the vehicle will be retrieved in three minutes, says Ranjit Date, founder-president and joint MD of Precision Automation and Robotics India (PARI), a Pune firm that designed and developed the parking system.

The New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) land on which this is built has been developed by DLF. The cost for car owners? A mere Rs. 10 per hour — for now. This is the price DLF is charging to encourage car owners to use this facility. Builders and PARI say Rs. 50 an hour is a more realistic price.

PARI installed a similar system, for 50 cars, at Chennai’s Saravana mall. It has been working for six months now.

So far, NDMC has tendered 43 public parking plots, but this is the first to open for use. It will soon be followed by a similar facility for 800 cars in Sarojini Nagar, also developed by DLF. Date is getting dozens of such proposals, and the Delhi project will be a test, not only for PARI but also for DLF and NDMC to see if this is the right approach to solving the parking problem.

PARI, a little-known company, has served the automotive sector with its industrial automation solutions for over a decade. In 2007, its two founders, Date and Mangesh Kale, decided that being sector-specific wasn’t a good idea. The early impact of the downturn on the automotive sector proved them right. In 2008, they decided to build automated parking systems also.

PARI’s flagship product, a fully automated parking system, costs half of what is available globally. The system multiplies a land’s car parking capacity by 16: If a plot can take 50 cars, the automated system can take 800. But, at Rs. 5 lakh a spot (PARI’s cost to build one parking spot), one could argue it’s for developers with deep pockets.

Date doesn’t agree. It’s an infrastructure issue; it’s no longer in the realm of economics, but public policy. Centres like Nariman Point and Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly, Victoria Terminus) in Mumbai have pockets of land that can be converted into such parking spaces. “It can solve the problem [of parking] overnight,” he says. Builders seem to agree: “This is the future,” says Pradeep Khanna, director at Bharti Realty, who is considering this solution for old and new properties.

Small Beginnings

Outside PARI’s five acre campus in Narhe, Pune, that houses 460 of its 960 employees, scores of cars are neatly parked. Doesn’t it need an automated parking system for its own use, you wonder?

Inside, several robotic systems are under development. A hydrostatic probe for in-service inspection of steam generators for Nuclear Power Corporation of India is in the final stages of shipment. Next to it is a surgical arm prototype, something like the $2 million Da Vinci robotic instrument from the US firm Intuitive Surgicals. A few feet away stands a hulking nuclear waste disposal system, a smaller version of which is at Mumbai’s Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. But, for now, car stackers and the automated parking system is occupying minds and space.

From 1990 when PARI was incorporated, to 1993 when it sold its first industrial robot to Philips, to until 2007, it served the automotive and consumer appliances industry. The likes of General Motors and Honda formed the clientele. In 2007, Date and Kale decided to diversify and decided on automation in car parking and logistics.

By then the company’s R&D and manufacturing foundation was already set. In a way, it was the culmination of a long journey for these Pune College of Engineering graduates. These school friends were college buddies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), New York. The long association is evident when they talk — one takes off from where the other stops. The complementarity — Date is an optimist with a we-can-achieve-anything viewpoint; Kale goes after detail and execution — is deep rooted. That’s perhaps the secret behind them visualising a business in the 1980s, when they were students and when the manufacturing world was moving on without much of robotics, and India was focussed on cost.

“We thought if we can make automation cost-effective and pitch it as a disruptive or high-performance tool, it would make for a good business model,” says Date. Their time at RPI helped cement the idea. While they were students there, RPI pipped other US engineering schools to win a $10 million robotics project from NASA. “We learnt a lot from that,” remembers Kale.

Applying the learning to their start-up wasn’t easy. There was no precedence in India for robotics. “We had to do everything from scratch — design, manufacturing, testing, manpower training. We began with just four engineers,” they recall, proudly adding that now they hire 620 graduate engineers. With Rs. 40 crore in private equity investment from Axis Holdings and a Mumbai-based high net worth individual, PARI’s 2010 revenue was Rs. 260 crore. It is developing a 73-acre manufacturing unit in Shirwal, near Pune, earmarked as one of the 110 mega projects by the state government.

Cracking the Parking Code

All the expertise was put to test when they decided to locally develop a car parking system. “We could have forged a collaboration with an overseas company, but we decided to do it ourselves to keep it cost-effective,” says Kale. “It wasn’t rocket science, yet it involved some invention and a lot of innovation.”

In general, entry-level systems are simple electromechanical ones, assembled as per needs. They, however, need attendants to operate them. Then there are stack systems, which come in packs of nine stacks that allow vehicles to be moved at the push of a button and can accommodate 14 cars. But it’s the fully automated system that is catching the imagination of the builders.

Complex algorithms, robotic arms, automation tools, and various sensors ensure that a car driver looking for parking space can take a rest from the survival-of-the-earliest syndrome.

Most of the systems available from multinationals provide similar solutions. So what is the invention here and where does the innovation lie?

Invention is in the combinatorial mathematics that defines the optimal path for the machines and other similar in-built intelligence, says Kale. The innovation, says Date, is in the system’s compactness, and hence cost-effectiveness. PARI’s technology is 25 percent more space efficient (in the way it uses space for parking) than the alternate international technologies. “None of the conventional mechanisms would allow parking and retrieval in so [little] space.” PARI’s design is meant to handle very high arrival and departure rates, common in Indian public places.

For reliability, enough redundancy has been designed into the system to ensure that no single failure impacts the customer. “For instance, if one robotic arm fails to retrieve the car, the second one will ensure the job is done. We’ve reduced the unreliability to statistically impossible levels,” says Date.

DLF says it is “quite satisfied with the installation” and is looking forward to using mechanised systems.

Cost versus Price

For commercial and residential buildings, these systems make much sense. Builders have realised the trade-off between the higher cost of such infrastructure and the eventual price of unhappy customers. “It [trade-off] is pretty good. What does a customer want, comfort?” says Bharti Realty’s Khanna. Moreover, builders find the ground coverage getting restricted in many large projects. “At Delhi international airport, [owing to international standards] I will have to go six basements down. That is more expensive than installing this system.”

Even in residential projects, builders think, this could enhance saleability, with families buying more than one car. Awinash Pustake, assistant vice president at Ackruti City in Mumbai, who is evaluating this system for an upcoming luxury project on Mumbai’s Peddar Road, says, “This brings value to the building; it costs more [than building a basement or podium-based parking] but saves a lot of hassles.”

Ackruti has installed German and Korean systems in two parking places, one commercial and one public. Pustake thinks a local system scores over imported ones. “Not only is the cost lower, but serviceability is better. Imagine having a broken cable and waiting for a month for a replacement, as it has to be shipped from Germany!”

Anticipating this as key to adoption, PARI has started signing separate contracts for maintenance and operation.

Public parking and transportation will certainly benefit: Free or under-priced parking on roads doesn’t add to a city’s revenues and affects traffic flow. Urban planning departments “don’t yet see this as a problem, it’s somewhere low on their priority,” says Swati Ramanathan, co-founder of Janaagraha and chairperson of Indian Urban Space Foundation. She thinks urban bodies should look at it as a source of income.

Part of the challenge, says Ramanathan, is the land use if private developers are to be encouraged. Public land, leased to firms, for developing public parking is a viable model. NDMC leased the Connaught Place land to DLF for 30 years and allowed two floors for a shopping complex, which is an incentive. “More participation from the government is expected as such projects are highly capital intensive and are not viable without cross-subsidisation,” says DLF spokesperson Sanjey Roy.

Back at PARI’s Pune campus, Date shows another prototype, meant for outdoor use — one that can make parallel parking on streets a double-decker system. Yet another parking system?

“In other countries, only some cities are congested, for instance, Paris or New York where parking is a nightmare; but in India, parking is a nationwide problem,” says Kale.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)