Haryana: The State of Discontent

From the Honda unrest in 2005 to the Maruti strike in 2011, industrial relations in Haryana have gone from bad to worse

Shop No. 19 is a dark, dingy cubby-hole near Gaushala market on Mata Road in the heart of Gurgaon, the capital’s gleaming satellite city that is home to the plush offices of Indian and foreign multinational corporations and luxury gated communities that house the executives working in them. A table stacked with papers and files hides two chairs behind it. Three walls of the room are pockmarked by peeling plaster and the fourth is covered by a huge photo poster of police trying to disperse a crowd with lathis. Beneath the photo is a slogan in Hindi that loosely translates to ‘Let’s come together to make this bandh successful’. It is the Gurgaon headquarters of the All-India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), India’s most powerful trade union.

Anil Kumar, the dark, burly general secretary of AITUC, Gurgaon, is dressed in a frayed white shirt with the first two buttons off, black trousers and no footwear. He speaks with a strong Haryanvi accent and spends most of his time at Shop No. 19 as he doesn’t really have a job. Kumar has a criminal case against him. A few years ago, he was accused by the Haryana police of killing a worker during the Rico Auto labour strike. He says he didn’t do it. As things turn out, a 13-day labour strike at Maruti Suzuki’s Manesar plant has made Kumar an important man.

Between June 4, when the strike started, and the night of June 16, when it was officially called off, Kumar and his comrades at AITUC also provided the muscle power and rallied support from workers in other companies. Ask him the reason behind the strike and he answers almost half asleep (he says he hasn’t slept for days), “the labour department of Haryana is working together with the manufacturers to stop workers from forming a union.” The flashpoint for the strike was the dismissal of 11 workers by Maruti Suzuki. The company did not officially respond to Forbes India’s telephone calls, text messages and email questionnaire. The company’s human resources head, S.Y. Siddiqui, says that no one in the company will be available for comment until June 27 as there is an annual maintenance shutdown. However, speaking on condition of anonymity, a Maruti official said that the 11 workers were sacked on the ground of indiscipline. “As the shift ended at 4 o’ clock these workers, without provocation, instigated other workers to start the strike. There was no warning, no charter of demand or anything. These guys just went on strike,” he said. However the workers have a different version.

Curbing A Constitutional Right?

Kumar’s allegation is only one among a plethora of reasons, such as low wages and overuse of contract labour threatening to undermine this burgeoning garments-to-cars hub that has been an integral part of India’s industrial growth and globalisation story ever since Maruti Udyog set shop here to produce the iconic Maruti 800 in the 1980s. However, this seems to be the main sore point.

“If one were to isolate one single factor [contributing to industrial strife], it is the [resistance to the] right to organise,’’ says J. John, executive director of Centre for Education and Communication and editor of Labour File a bimonthly journal on worker issues. “In many cases, there is no demand for even a wage rise; just to form a union.’’

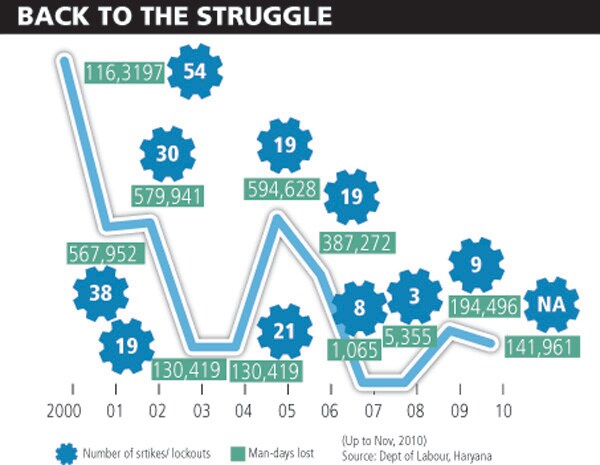

Almost every strike at the numerous factories in the Gurgaon-Manesar region in the past decade has started with companies refusing to recognise the demand of workers to form a union. From the strike at Maruti in 2000 to the one at Honda Motorcycles and Scooters India (HMSI) in 2005 and the one at Rico Auto in 2009, the one common demand was to form a union.

“It is a constitutional right,” says D.L. Sachdev, a secretary of AITUC. “Nobody can prevent the workers from forming a union.” Statistics, however, tell a story of effective prevention.

The number of registered factories in Haryana nearly doubled from 5,652 in 1991 to 10,474 in 2010, while the number of registered (permanent) workers grew from 3.5 lakh in 1993 to more than 7.7 lakh in 2010. (The increase in the number of contract workers has been vastly more.) In comparison, in the past two decades, the number of registered trade unions have grown by merely 400 to 1,540, says data from the State Labour Department.

AITUC strongly believes that Haryana has lured huge investments with an unstated promise to keep the region free of labour unions. Maruti has stated publicly that it does not want to deal with more than one union. The company says it already has a union, the Maruti Udyog Kamamgar Union (MUKU), at its Gurgaon plant and if workers at Manesar want a union, they should come under the MUKU umbrella. Plant-specific unions are, however, not uncommon in the industry. Several companies such as Ashok Leyland or Apollo Tyres work with separate unions at each of their plants.

“How can a labour union of Plant A represent the issues and needs of workers in Plant B? When the workers of a particular plant want a union it is because they can have collective bargaining power, better working conditions among other things in their own plant. I don’t see what is the big deal in this,” says R. Kuchelan, president of the Working People Trade Union Council.

Some believe that the real issue is the hostile attitude of multinationals towards labour unions. Dr. R. Krishna Murthy, director of the Industrial Relations Institute of India believes Japanese companies have an anachronistic attitude. “In India, these companies have adopted a tyrannical attitude and don’t believe in openness. They need to have a certain degree of maturity to deal with the issue but [many] Japanese [officials] who come here are ignorant of the local realities and this is true of all Japanese companies,” he says.

Labour File’s John says that Indian companies perhaps treat employees better than many foreign companies operating in the country. According to gurgaonworkernews.com, a Web site that documents labour issues in Gurgaon-Manesar-Faridabad industrial areas, there are 192 automobile companies and component makers in the belt that are partly or fully owned by foreigners.

Unions Fight To Get

Registered, Recognised Within an hour, shop No. 19 is full. Workers finishing the day shift come straight to the union office to discuss their problems and seek advice. There are people from Maruti, HMSI and a small ancillary unit called Napino Auto. They hail from different states — Bengal,

Bihar and Haryana, among others.

Once it is a full house, the boss walks in — Arvind Gaur, president of AITUC, Gurgaon, and also the chief of the union at HMSI. He and Kumar sit at the table. Tea is ordered and Gaur lights a ‘chota’ Gold Flake cigarette. Soon, stories and experiences are narrated and strategies discussed.

Gaur does not like MUKU. In the union circles, people refer to MUKU as a ‘pocket union’, a management prop. Gaur is pretty unsettled by the fact that MUKU’s flag is flying high at the company’s Manesar plant. He thinks it has no business being there because the workers there want a union of their own. “These people don’t trust MUKU. It is a puppet union. Even its leaders are appointed by the management. So how is it a workers’ union,” he asks. This means that MUKU’s flag needs to be replaced with the AITUC flag.

Any organised action requires effective leadership. However, the central trade unions are constrained by an amendment to industrial laws in 2002 that considerably reduced their power. If the factory is in a special economic zone, no external office bearer is allowed. That means the leadership for any

action by workers has to come from within each factory.

Most factories today have an entirely new generation of workers, very different from the old guards of the public sector that was the backbone of central trade unions. A majority of workers in Haryana’s industrial belt are north Indian, with an agrarian but educated background. “They are a non-politicised group,” says CEC’s John whose journal has documented industrial disputes in this region.

Unilateral action from these workers tends to be weak and they need the back-up of the central trade unions that have political clout. It was demonstrated in the strike at Maruti. AITUC leaders Gurudas Dasgupta and Sachdev, along with INTUC leaders, met the Haryana Chief Minister Bhupinder Singh Hooda more than four times, almost pushing him into action.

Hooda finally directed Deputy Labour Commissioner J.P. Mann to personally be a part of the negotiations and bring about an amicable settlement. In spite of the high level intervention, the final agreement thrashed out between the management and workers did not mention anything about allowing the workers to unionise. It merely reinstated 11 workers who were sacked. AITUC’s Sachdev says it does not matter. The registration of the union is pending with the government. And once the union is registered, there is little that the company management can do. Earlier this week, CEO Osamu Suzuki said, at a news conference in Tokyo, that he was not surprised at the short lived labour strike and that Maruti would not recognise a second labour union for its plant at Manesar.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Why Companies Don’t Like Unions

Perhaps this is the reason why companies don’t like labour unions: Unions are politicised, messy and the management is never quite sure of their motivation. “Anybody who has dealt with a labour union knows how ridiculous it can get at times. The balance rests on a very thin line and most of the times it is a compromise. All your theories of motivation go out of the window and it is mostly horse trading,” says a former plant manager of an automotive manufacturing company who did not want to be named.

He recounts an incident where the whole engine assembly line was stopped for about three hours by angry workers because one of the workers found an ant in the sambhar that was served during breakfast. Almost immediately, a few workers started pretending that they were really sick and were taken to the first aid room. In the meantime, angry workers poured the sambhar down the drain and asked the canteen to prepare it again. Only after fresh sambhar was prepared and they finished their breakfast did they return to work. “And still the guys who had gone to get first aid were missing. When you have a target to achieve and something as insignificant as this holds up your line, then what do you do? We had a production loss of Rs. 21 lakh that day,” he says.

Worker agitations, not just official strikes and lockouts, over the past few years have been getting increasingly frequent, acrid, even violent. After the 2000 strike at Maruti, more than 200 workers were sacked, and over a period of time close to 800 were forced into voluntary retirement. In 2009, the Rico Auto strike ended in the police resorting to lathi charge and firing, leaving one worker dead. It had started with a demand to have a water cooler removed from the washroom.

For the companies, a cheap and convenient way to avoid unions and possible agitations is to hire more and more workers on contract.

Contract Labour: A Way To Keep Away Trouble

In more ways than one, this is the dark, ugly secret of the Indian manufacturing industry. According to the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector, total employment in the Indian economy in the five years from 2000 increased from 39.6 crore to 45.6 crore, of which 5.8 crore was of an informal kind.

“What this means is that the entire increase in the employment in the organised or formal sector over this period has largely been informal in nature i.e. without any job or social security. This constitutes what can be termed as informalisation of the formal sector, where any employment increase consists of regular workers without social security benefits and casual or contract workers, again, without the benefits that should accrue to formal workers,” says the commission, better known as the Arjun Sengupta Committee.

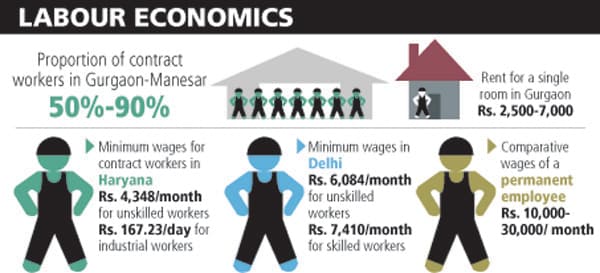

For example, in HMSI, out of 5,900 workers, 4,000 are on contract and 1,900 are permanent. A contract worker has no rights, no union to protect him and earns about Rs. 7,000 a month. A permanent worker earns close to Rs. 30,000 a month, has rights, a fixed number of holidays, 39 to be exact, and union cover. And they do the same job.

“This is unjust and unsustainable in the long run,” says the CEO of a large two-wheeler maker who did not want to be identified. But somehow the whole eco-system has been perfected to make it work. According to the law, a company cannot employ a contract labour for more than six months. To get around this rule, the worker is discharged every six months for three days and reinstated as a fresh employee.

The law does not allow contract workers to be employed in activities that are of “a permanent and repetitive nature”. However, this rule is observed mostly in violation. Small ancillary units have up to 90 percent of contract workers. Do the unions fight for the cause of the contract labourers? Yes and no. It suits permanent workers if some strenuous jobs are done by temps. If he protests, the company can summarily sack him but he forms an important part of the eco-system. In the garb of gaining more clout with the company, reducing the head count of contract labour by making them permanent is an evergreen issue for unions.

Tough Road Ahead

Workers are influenced by politics from the outside,” says Surinder Kapur, chairman and managing director of Sona Koyo, an auto parts manufacturer. “To my mind, the problem in India is that there is no exit policy. So the workers don’t care, the management takes a tough position and in the end, it is the suppliers and customers who suffer,” he adds.

It is a fair point. For instance, who will be accountable for the Rs. 500 crore losses that Maruti has incurred? Nobody. “It is not that the manager’s salary in the management goes down or the workers’ wages are reduced. Here is a reason for industrial policy to change in India,” says Kapur.

Back at Maruti, Shiv Kumar is supposed to be the general secretary of the new union at the company’s Manesar plant. The new union’s registration is still pending and the Maruti management has made it quite clear that they will not allow a new union.

What Shiv Kumar and the rest of the comrades in Shop No. 19 are discussing is how best they can get workers in the Manesar plant to sign the union membership form. This form is nothing but a cover letter of the AITUC constitution stapled with five blank papers on which Shiv Kumar needs to get the signatures of the workers. They want to do it silently without the knowledge of the Maruti management. This means laying out tables and getting workers to sign is out of question. So is holding workers back before or after a shift. Also, the problem is that the Manesar plant has more than 10 divisions, so logistics is tough.

Gaur has a smart idea. “Do it in the bus,” he says. The idea is that once the workers sign the membership form, one set of the document, the original, will be sent to the management to inform them of AITUC’s strength and the other to MUKU. That’s how the union will get recognised.

“Labour unions are a reality and companies have to accept it sooner or later,’’ says Anil Kumar. He may well be right.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)